When the pandemic first started, I thought of all the men and women in prison I’d interviewed over the years. Even on the best days, prison can be a soul-crushing place. Now the pandemic was stripping away many of the things that make incarceration bearable: Visitors were shut out. College classes ended abruptly or moved online. Recreation time was limited. To make matters worse, many prisons are old, dank and crowded spaces. They are notorious for subpar medical care. If the coronavirus found its way in, it could spread like a deadly wildfire.

I began corresponding with several incarcerated people in March 2020. I wanted to know how they were surviving the pandemic. At the time, most facilities had few cases. But testing was limited, and eventually the cases began ticking upward. The men and women chronicled their daily routines. They’d share news of the first confirmed cases in their facilities. Some detailed their facilities' descent into a full-blown outbreak. At times we’d lose touch for weeks.

No two experiences of the pandemic in prison are the same. But many of the stories show how officials failed to properly prepare for the spread of COVID-19. The rich detail each person provided about their experiences lent themselves to illustration. Their stories are a visual reminder to not look away from what is happening to 1.3 million men and women in prison. The boredom, isolation, and fear brought on by the pandemic are intensified behind bars.

One year since the pandemic first began, four incarcerated people share their survival stories.

Bruce Bryant

Sing Sing Correctional Facility in New York Illustrated by Danica Novgorodoff

March 2020

My daily routine during the pandemic always starts off the same. I get up about 6 a.m. at the sound of an extremely loud bell and have to stand or sit up with the light on for the count. Then I turn on the news. Breakfast is between 7 a.m. and 8 a.m., but since there is no social distancing here, I stay in my cell and eat oatmeal. They call yard time at about 9:30, but I don't go to the yard either. We are literally piled on top of each other trying to get outside so we can get on a phone.

There are 22 phones in the yard — often fewer because some don’t work. There are 88 men per gallery with eight galleries going outside at the same time. If you are not in one of the galleries called first, the chances of you being able to call your family are slim to none. I am able to get to a phone about every three weeks.

March - April 2020

At the start of the pandemic, the superintendent began hosting “press conferences” in the chapel with various leadership organizations, including the Inmate Liaison Committee. He begins by outlining his concerns and efforts to keep everyone safe, then asks the attendees if they have any questions.

I have not attended those sessions, but I am thoroughly debriefed by the brothers when they return. The meetings relieve some of the stress and anxiety within the prison. However, each time someone passes out or dies, it draws everyone's attention back to the reality and heightens everyone's sense of vulnerability.

Every single night, I hear men coughing for hours. There are countless men who have symptoms: loss of taste and smell, headaches and chills. Some are afraid to be quarantined because it means they’d go to the SHU (solitary confinement).

April 2020

An incarcerated person must be extremely ill to be tested. It's amazing how scientists have the resources to test lions, tigers and other felines, but incarcerated people don't hold the same value, so we can't get tested. Many of us have underlying issues, like diabetes, asthma and high blood pressure.

In April, a guy named Ramon Escobar died. Several weeks before, he and I went to the clinic for a sick call. They kept him for a couple days and then brought him back to his cell. A few days later, he went to the hospital. Sixteen days later, he died while hooked up to a ventilator.

The prison has tried to distance us. In the dining area, they only allow four people at a table, and now you don’t have to wait for everyone to finish before you leave. They’re disinfecting common areas, too; they’re using bleach on the kiosk we use to send emails and on the telephones in the gym and on the yard.

But what difference does that make when they bring people who were diagnosed with COVID back from the hospital just because they are feeling better? They aren’t retested to see if they are still carrying the virus. And what difference does it make when the guards don’t wear masks?

April 2020

The guards know we can't get visits, so the only way for us to contract the virus is through them. But many act as if WE are the virus. I guess they are conditioned to view incarcerated people as subhuman.

There has been no compassion for us.

People whose family members have been hospitalized for COVID don’t get special access to the phones. When an incarcerated person has a civil proceeding, they conduct parts of it via video conference. But an incarcerated person can't connect with their dying mother via the same system.

A friend in the cell next to me had to literally argue with social workers in the counsel unit for a phone call after they called him to tell him that his mother was sick from COVID.

April 2020

We spent weeks writing letters to advocacy groups who might be able to help my friend, Francisco, get a video visit with his mother. She has been hooked up to a ventilator for weeks. She may very well pass away and Francisco wants to see her one last time.

Eventually the prison agreed to let him have a video visit. But right after he found out, he got another call to say his mom died.

May 2020

For the past couple of weeks, I’ve been knocking on the wall each night to check on Francisco. You never know what a person’s history is and what they are thinking in those dark moments.

When someone passes away all that matters is who his friends are. We try to console each other by listening. I always tell my neighbor I am praying for him. And sometimes I pray for all the guys dealing with sick loved ones on the outside.

Other than that it’s simply, “another one bites the dust.” There is no such thing as incarcerated people and the staff being “in this together.” There’s no compassion, and in some cases, there’s even less compassion than usual.

At the end of the day, people in prison only have each other. We often build real bonds. We have friendships that matter. I try to be a light in a dark place. Prison is a cold environment. It's up to us to create our own heat.

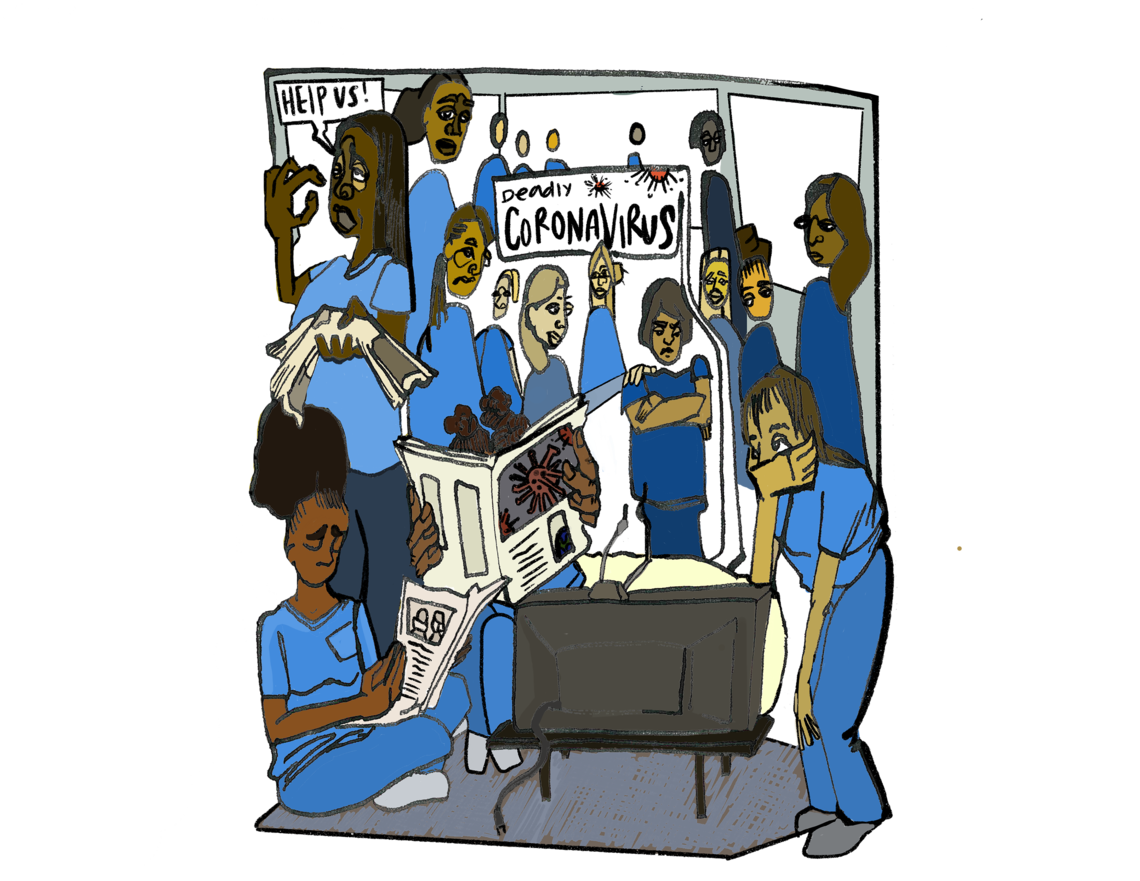

Jennifer Graves

Florida Women’s Reception Center Illustrated by Kayla Salisbury

March 2020

Truth be told, everything in prison is a fight.

Not a day goes by where you can just go up to an official and ask for assistance and receive it willingly. So as we read news reports of the pandemic, it isn’t surprising that the prison hasn't told us anything. There’s a rumor going around of one known case somewhere in the prison. One dorm was emptied, possibly to house “infected” inmates. But we haven’t been tested and we haven’t gotten any instructions.

It is scary to think about getting sick in here. The medical care we receive is equivalent to a MAS*H unit from the Korean War era. There’s no first response team and no ER doctors standing ready.

March 2020

If you have any symptoms of any sort you are asked to line up outside in the rain, sun, cold or heat to explain your needs to a nurse in front of the whole compound. Usually a nurse just tells you to go to the medical waiting room. After sitting there for hours, we’re often told to come back and go through the same process the next day.

Sometimes it takes three or four times before you are actually seen. And you are often belittled. Most nurses just give you ibuprofen and tell you to drink more water. Even though they don’t treat you, they still charge $5 for your visit.

March - April 2020

Preventive medicine is not the prison’s forté. You must be almost dead before you can actually receive care.

In late March, we started to worry when a doctor made rounds for the first time since the pandemic started. She instructed us to keep our hands and throats washed, even if it meant gargling with soap. She also suggested we keep our faces covered with a mask made out of toilet paper.

No one made a mask out of toilet paper. We thought it was ridiculous.

April 2020

Soon after the doctor made rounds for the first time, the prison started socially distancing us. Only one dorm at a time is allowed in the chow room, there are only two women per table and they told us we must remain 6 feet apart.

But I sleep in an open dorm with 78 beds, eight showers, 12 toilets and eight sinks. Our bunks are only 2 feet apart, side by side. I asked if we could sleep head-to-toe to make some distance, and the answer was “not yet.”

What are they waiting for?

We’ve also heard a rumor that we will receive 160 new commits from various counties. I hope they’ll be placed on a 14-day quarantine and take the virus seriously. But I have learned that not everyone wants to live. A lot of the women are like the fools who refuse to leave when a hurricane is headed their way.

I don't believe the world was prepared for any of this; it seems like most are walking in the dark with a pen light.

July - August 2020

My facility has over 180 cases of coronavirus. They tested the whole compound — over 700 women — and my unit was placed on a quarantine. No one can leave and the nurses come around to take our temperatures twice a day.

After I had a high fever, I was moved from my dorm to one that holds only 10 women. The nurses eventually tested me for COVID. When my test came back positive, they put me in an isolation unit. I laid in bed with a fever and chills wondering when I’d get out and back to my dorm.

I've heard there were some deaths, but I can’t be sure. No one tells us anything.

Eventually I recovered enough to be moved to a recovery dorm with 11 other women. The journey has been long, but my care was adequate. Laundry was done every day. The food came on time. They even made a way for us to receive canteen while we are on quarantine.

August 2020

I am currently in the 18th year of a life sentence at Florida Women’s Reception Center. I didn't grow up here in prison, but I am growing old here.

I have had to learn to mature and cope under serious adverse circumstances in an extremely hostile environment. I will not lie: This has not been an easy road, but I understand that it is not intended to be.

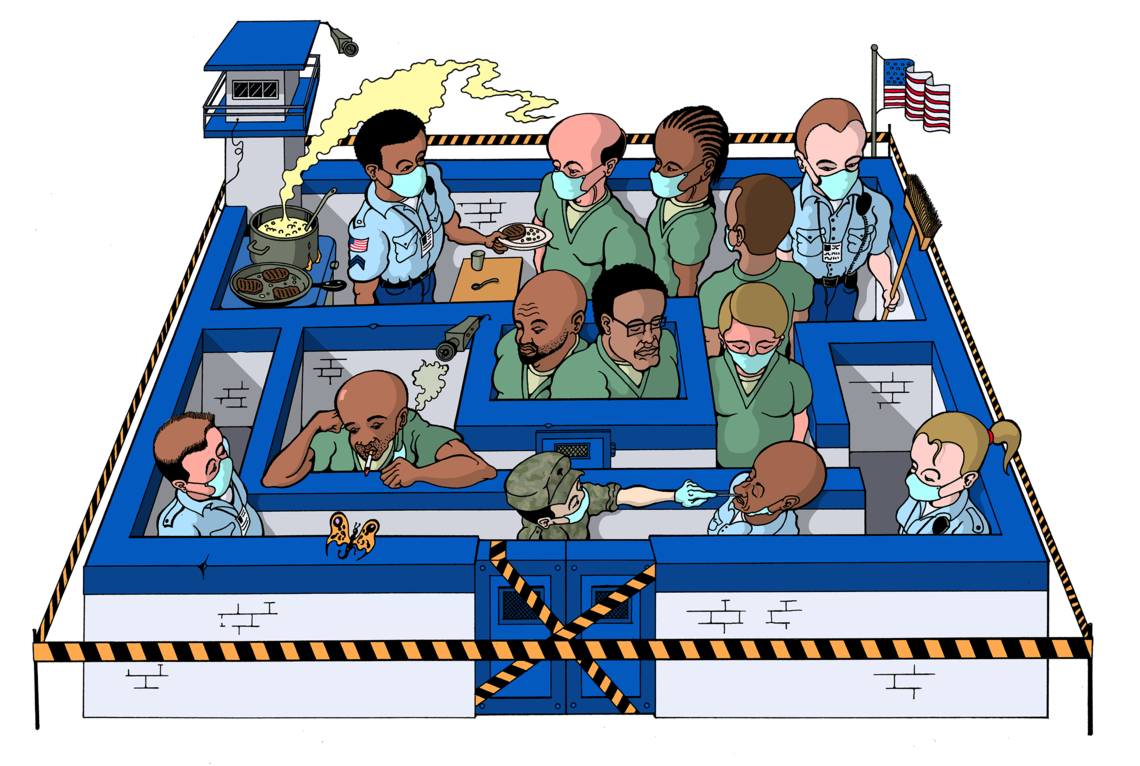

James Ellis

Marion Correctional Facility in Ohio Illustrated by Hannah Buckman

April 2020

When we first heard about COVID-19 on the news, we thought we would be safe from the virus because people in prison have very little contact with the outside world. We knew there was a risk of staff bringing the virus in, but for the most part we felt like we were the lucky ones.

Then a guard got sick.

When we found out he had COVID-19, panic set in. Everyone talked about which areas of the building the officer had been in. Then other officers started getting sick.

“It’s here. It’s here, the virus is here,” people exclaimed.

April - May 2020

Soon after the first guard fell ill, prisoners started getting sick too. They’d pass out or lose their sense of taste and smell. Some would have trouble breathing. One after another, the guys were getting rushed out while the rest of us sat back in our corners, worried and waiting. Out of the windows of our housing unit we were able to see multiple ambulances pull up to the prison’s back gate and pick people up.

After so many prisoners got sick, the governor decided to test the entire prison population. After we got our results, the prison decided to separate people who tested positive from people who did not have the virus. But that didn’t last very long, because the staff were trying to make the moves on their computers instead of in person. Lines got crossed. They made mistakes. Inevitably, positive prisoners got mixed together with negative ones.

April - May 2020

After we were tested, some of the officers stopped showing up for work. We felt like they had left us to die. On the inside, it felt like we were in the basement of a burning house with no way out. Some of the guys began having prayer circles. They would get in a circle and hold hands and pray to God.

April - May 2020

Members of the National Guard who had conducted our testing stayed to run the facility. Many of the guardsmen were cool, but a few came in with their chests poked out. One guardsman who did temperature checks and tested our blood oxygen level with a finger monitor was like this.

One day, when it was my time to put my finger in the clip, I refused. He asked why, and I told him it was because he wasn’t sanitizing the monitor after each person. “If one guy is sick, then it could possibly get us all sick,” I said.

“So you are refusing to be tested,” he said, stepping toward me as if to intimidate me.

I shot him a surprised look, and his partner told him to let it go. But after other people heard our exchange, they refused the finger monitor too.

Sometimes I’d talk with the other guys about what we could do to let people know about our conditions. We’d see on the news that our prison was the number one hot spot in the country. We started sending out videos showing the conditions. We told our loved ones to share our stories on social media.

The governor wasn’t doing anything to get us relief. And some of the guards still refused to wear masks. There are people in here that treat us like we are not human. The ones that do, their co-workers call them “inmate lovers.”

May 2020

Eventually, I got sick too. When I first caught COVID it felt like the flu, but as the days passed, my symptoms got worse. My body hurt all night. It was a challenge to sit up straight. After those symptoms faded, I lost my sense of smell and taste. My mouth felt numb and my joints ached.

Having COVID was terrifying. The virus had put others in the graveyard at an alarming rate. I was sick for a couple of weeks. I think some of the other guys might be “long haulers,” but they won’t say anything about their symptoms because it could mean winding up in isolation. When you’re isolated, you lose a lot of your personal property. No one wants to take that chance.

January 2021

With the outbreak in our prison behind us, a new sickness has set in. Some of the guys are showing signs of mental health issues. They’re walking around lost and in a daze. Some are doing strange things for attention. Others are getting high off anything they can find; they’re smoking paper with bug spray on it.

Staff have to monitor the hand sanitizer because guys pour it into a cup, stick it in the microwave to burn off chemicals, and mix it with pop or Kool-Aid. They drink it because there is alcohol in it.

Someone said once that pressure can bust pipes. In extremely challenging times, it is either going to bring out the best in someone or the worst, depending on how mentally strong they are. I believe that the pressure and the fear of this pandemic has pushed people here to their breaking points.

Christopher Walker

Stanley Correctional Institution in Wisconsin Illustrated by Acacio Ortas

April 2020

In early April, my cellmate was using the phone in the dayroom when someone heard him cough twice. Since March, we’d been hearing about the coronavirus, and the state was under a safer-at-home order. Someone reported my cellmate’s coughing to an officer. That’s when the fiasco began.

The officer sent my cellmate to the nurse’s office. One nurse said it was nothing, he told me. But she got a second opinion. That nurse came in, took one look at him, and decided he looked sick. So they sent my cellmate to an empty unit to quarantine.

As I was coming back from cutting hair in the gym, a C.O. found me.

“What is going on,” I asked?

“You’re being sent to quarantine,” he said. “Pack up your things.”

April 2020

Together my cellmate and I have 57 years of stuff we’ve accumulated throughout our incarceration. I took our pictures off the wall. I packed my essentials: A fan, TV, radio and headphones. My most prized possession is a bottle of prayer oil that costs $4.30 an ounce. I spray it in the air to cut all the smells of prison. It took 22 bags in total. Two other prisoners helped me carry our things to the quarantine unit.

April 2020

When I got to the unit, I asked if I could be in a cell next to my cellmate. But we were locked in together. I guess they figured if he was sick, I had already been exposed. But there was no way to know. At the time, the CDC was only recommending testing if people showed symptoms, and I didn’t have any.

I also thought about all the other guys I had contact with as a barber. I probably cut nine heads a day, so 45 people a week. If I was sick, wouldn’t they be sick too?

April 2020

Quarantine was tough. We were stuck in an 8-by-12 foot cell with nowhere to sit except for the bunk and no way to social distance or properly disinfect the room. We could only shower every other day. We couldn’t go outside and get fresh air or wash our clothes. We had no access to the microwaves or the kiosk to send emails. A nurse came by every day to take our vital signs.

The worst part was that every 10 weeks, the prison would let us buy a frozen pizza to enjoy on the weekend. As the guard walked me to quarantine, I asked, “What about my pizza that I have already paid for?”

He said he’d find a way to have it cooked and brought to me. I knew that didn’t sound right. Of course, Saturday came and went, and I never got any pizza.

April 2020

We should have known how quickly the virus would spread. Just a few months before we had a COVID outbreak, the norovirus spread through the facility. Guys were stuck in their cells throwing up and using the bathroom at the same time. It was awful.

COVID-19 was no better. The body aches were terrible. It just felt like I was being crushed or punched all over my body.

The lockdown was hard on the guards too. They had to cook the food, clean the showers, wash the laundry and pass out the mail. These are all jobs that the state usually pays incarcerated people 12 cents an hour to do. Under normal circumstances, the guards just have to make sure they get the count right and hold onto their keys. Now they were working overtime.

April 2021

This month will make 28 years behind bars for me. There has been no worse year than 2020. But I have to tell myself I am not a victim, even if I have felt victimized at certain times.

When you have a lot of downtime, the brain wanders. The old “coulda, woulda, shoulda” syndrome kicks in. The reflection is harder because I am so close to getting out. I’ve been in front of the parole board three times since 2019. I was supposed to be transferred to a minimum-security facility last year. That’s the step before going home. But the pandemic paused all transfers between facilities.

Right now I am filled with a feeling that the door is opening slowly. It’s another deep-breath moment. I can see why some people don't come out of this alive. Surely, nobody comes out of it the same.

Credits

Illustrated by Danica Novgorodoff, Kayla Salisbury, Hannah Buckman, and Acacio Ortas

Art Direction by Celina Fang and Bo-Won Keum

Design and Development by Bo-Won Keum and Gabe Isman

Support The Marshall Project