A nonprofit news organization covering the U.S. criminal justice system

Topics

About

Feedback?

support@themarshallproject.org

Our reporting with the Kentucky Center for Investigative Reporting revealed that Kentucky State Police had the worst fatal shootings record in rural communities of any agency in the country, with 41 people fatally shot from 2015 to 2020. The lack of video evidence meant many of these incidents escaped scrutiny. Shortly after we published on the front page of The New York Times and the Lexington Herald-Leader, Gov. Andy Beshear requested $12.2 million to equip the State Police with body cameras. Lawmakers approved the expense in spring 2022.

The Marshall Project is a journalism outlet, not an advocacy organization. We don’t approach any issue with an outcome in mind. Our reporters examine all sides of an issue and follow the facts where they lead. We focus on criminal justice as an arena where power is often abused; our goal is to expose injustice.

The Marshall Project’s work frequently leads to real and demonstrable change. We track the impact of our journalism on three important groups: policymakers; advocates and criminal justice experts; and other media. Each has a critical role to play in improving the system.

Since our founding in 2014, The Marshall Project’s reporting has spurred new legislation, prompted official probes, improved conditions in specific prisons and jails, gotten people out of detention, and been cited by everyone from Supreme Court justices to jailhouse lawyers.

See our latest impact reports.

None of this impact would be possible without supporters like you. Please consider donating to The Marshall Project.

Support The Marshall ProjectOur reporting on how hospitals use drug tests to separate mothers from their newborns triggered civil rights complaints and prompted legislators to ask questions. In September 2024, we revealed how mothers could be separated from their newborns for false positive drug tests, which could be triggered by something as benign as a poppy-seed bagel. Done in partnership with Reveal, Mother Jones, and USA TODAY, it was one of our most widely read stories of the year. And in December, we published a follow-up about mothers with no history of drug use who could be separated from their babies for weeks or months after testing positive for medications prescribed by the same hospitals conducting the tests.

The response has been widespread. The national ACLU convened a working group of affiliates across the country to discuss the issue of hospital drug testing and reporting, and more than 20 affiliate states are now interested in pursuing litigation on behalf of patients who’ve been drug tested and reported. Sen. Tim Scott also added the issue to his legislative agenda for the year.

The local sheriff’s department revised its policy on publicly releasing bodycam footage after we pressed for footage of a deputy’s shooting of a teenager in downtown Cleveland. In the wake of a joint The Marshall Project - Cleveland and News 5 Cleveland investigation in February 2025, the Cuyahoga County Sheriff’s Department finally released footage of a deputy’s shooting of a teenager, nearly four months after the fact. The department also changed its policy on publicly releasing body cam footage.

We knew footage from the October incident existed, but the sheriff’s department refused to share it. Working side-by-side with News 5 Cleveland, we kept asking for months. And just hours before we were going to publish our investigation into their refusal to release the video, they sent us the video. We worked to immediately rewrite our story, knowing that our persistence had applied enough pressure to force transparency and accountability.

Unlike the Cleveland police, the sheriff’s department did not have a policy on releasing officer bodycam video. But now that’s changed. Later in February, the department quietly updated its policy to allow the release of body cam footage within seven days.

Washington state legislators proposed legislative changes after our investigation into how a law meant to protect health care workers had led to prosecutions of people with severe mental illness. A group of Washington state legislators proposed a law that would exempt people receiving in-patient mental health treatment from an automatic felony assault charge, after our investigation found that the majority of these prosecutions are against people with serious mental illness. In June 2024, we partnered with The Seattle Times to look at how a Washington state law intended to protect health care workers — by elevating low-level violence to felonies — instead led to patients in mental health crises being punished for behavior that landed them in the hospital in the first place.

Cuyahoga County Judge Leslie Ann Celebrezze has admitted to steering lucrative divorce cases to a friend working as a receiver for the court after our reporting uncovered the relationship. In March 2025, prominent local Judge Leslie Ann Celebrezze formally admitted to funneling lucrative divorce cases to her longtime friend and court-appointed receiver, Mark Dottore. The Marshall Project - Cleveland first surfaced Celebrezze’s relationship with Dottore in June 2023. The story originated from a tip we received, and since that report, the judge has been removed from the divorce case that sparked the inquiry. She is also now under federal investigation as of February 2025 and faces multiple misconduct charges from the Ohio Disciplinary Counsel.

Ohio passed legislation to end debt-based suspensions to help drivers get their licenses back after we reported that the state had issued nearly 200,000 new suspensions in a year. Near the end of December 2024, the Ohio legislature passed House Bill 29, which addressed the state’s driver’s license suspension crisis. Once the legislation becomes law, Ohio will join its neighboring states that have eliminated debt-based suspensions in recent years. As a result, hundreds of thousands of Ohioans could soon be able to get back on the road legally.

The legislation followed a Marshall Project - Cleveland and WEWS News 5 investigation that found the Ohio Bureau of Motor Vehicles issued nearly 200,000 new license suspensions in 2022 for debt-related reasons such as failing to pay court fines or missing child support payments.

After we reported on Cuyahoga County’s lack of reentry services, county jail officials are finalizing a program intended to help people meet basic needs upon being released from jail. As of November 2024, jail officials in Cuyahoga County, Ohio — home to Cleveland — are finalizing a reentry program intended to give people released from the county jail access to resources about housing, employment, health care and other essential services.

The changes came one year after The Marshall Project - Cleveland detailed how few of these services were provided to newly released prisoners.

“This is a step in the right direction,” said Evan O’Reilly, a spokesperson for the Cuyahoga County Jail Coalition, a group advocating for change in the county justice system.

“Cutting people loose with no assistance is not good.”

One Oklahoma county announced it was seeking a new health care provider for its local jail, following our reporting on poor care for patients. Another county announced it would investigate. In July 2024, The Marshall Project and The Frontier published an investigation focused on Turn Key Health Clinics, a private company that has contracts to provide medical care for more than 75 jails in at least 10 states. At least 50 people in Turn Key’s care died during the past decade. We took a close look at several of these cases. According to government records, in some cases, the company’s employees didn’t send critically ill people to hospitals. In others, records showed that local sheriffs complained about prisoners not getting proper medication.

In the wake of our investigation, officials reevaluated the Oklahoma County jail’s relationship with Turn Key and made plans to consider options for a new medical provider for the jail, which serves Oklahoma City. Turn Key, which had offered a discount to the county to renew the contract for the jail, then announced it would exit the new contract after 30 days due to “understaffing” of security at the jail. Records show that Oklahoma County’s jail was one of the larger ones in which Turn Key operated as a health care provider. Also in Oklahoma, Cleveland County hired a firm to look into deaths at its jail, where two people featured in our story died.

Through Investigate This!, we helped at least 20 different outlets publish a different kind of election story — one that featured the political views of incarcerated people. Leading up to the 2024 presidential election, The Marshall Project published a survey of the political opinions of incarcerated people. More than 54,000 people in nearly 800 facilities across 45 states and the District of Columbia responded to our survey. The poll showed that former President Donald Trump remained popular behind bars, and opinions were split on Vice President Kamala Harris. Our local Cleveland newsroom also looked at results in Ohio, where nearly 3,000 people in 31 prisons and 20 jails across the state responded.

We also developed an Investigate This! toolkit featuring state-by-state results, which helped inform stories published by at least 20 different outlets across 11 states. These outlets included the Houston Chronicle, The Oklahoman, WBEZ in Chicago, St. Louis Public Radio, AL.com and several across Ohio.

After our 2020 story on the horrors of the jail in St. Francois County, Missouri, county officials reached a $1.8 million settlement with the parents of a man who died inside. Although it won’t bring their son back, officials paid $1.8 million to the parents of William “Billy” Ames III, and several plaintiffs also filed a federal class action lawsuit against the county and its sheriff that cited our reporting. The lawsuit alleged “unconstitutional, discriminatory, and dangerous conditions while detained pretrial at the St. Francois County Jail.” The lawsuit eventually became a key issue in the 2024 Republican sheriff primary, when voters in the county ousted Sheriff Daniel Bullock after 32 years.

In March 2024, sources in St. Francois County said that, as a result of our reporting, there appears to be more medical care and less use of force in the jail, and there have been fewer reported deaths. The evidence is anecdotal, and the conditions still appear to be far from good, but there are no longer reports of “Friday Night Fights” set up between detainees by the staff, which our story revealed, and there are more medical staff to provide care. A federal class action lawsuit against the jail remains ongoing.

Cuyahoga County Juvenile Court canceled a contract with a youth care center provider after we surfaced social media posts advocating for abuse. In August 2024, the Marshall Project - Cleveland took a close look at the private youth care centers that Cuyahoga County Juvenile Court officials have been sending kids to in an attempt to alleviate overcrowding at the detention center.

We found that these centers lack oversight and have not helped improve outcomes for kids or reduce the detention center population. When we highlighted social media posts from one youth care center’s operator touting that “one lick from that cord” could set kids straight, court officials terminated its contract a day later.

The Language Project, our series on the impact of words used to describe incarcerated people, prompted several newsrooms to reconsider their language and influenced the “style bible” of American journalism, the AP Stylebook. Reporters and editors have long believed that terms such as “inmate,” “felon” and “offender” are clear and neutral. In 2021, we published The Language Project, which included our own essay explaining The Marshall Project’s decision to avoid labels such as “inmate,” while also making the case for “journalism as a discipline of clarity.” As part of the project, we also pulled together essays from formerly incarcerated people, corrections officers and language experts on the issue.

In response, The Poynter Institute created a virtual workshop that was attended by more than 300 people from newsrooms across the country. The NPR program “On the Media” featured a segment with our editor, Akiba Solomon.

In May 2024, The Associated Press issued a new edition of its Stylebook, widely seen as the style standard throughout the industry. It included a new chapter on criminal justice that encourages people-first language and discourages writers from using terms like “felon” and “convict.” In a press release announcing the new section, the AP said that “the chapter was primarily written by a team of AP criminal justice reporters and editors, who attended trainings by Poynter, and others and consulted with The Marshall Project, among additional research.”

The importance of person-first language came to the forefront following former President Donald Trump’s conviction in early June 2024. Marshall Project president Carroll Bogert penned an op-ed in The Washington Post, “Don’t Call Trump a ‘Felon.’” It appeared in print at the top of the Opinion page and had roughly 184,000 views in the first week. The discussion picked up steam after that, with The Wall Street Journal and NPR also dedicating space to the topic.

Local advocates called for an investigation into how the Cuyahoga County courts assign counsel to children after we reported that most cases went to a handful of private attorneys. In March 2024, The Marshall Project - Cleveland looked at how judges in Cuyahoga County steer juvenile cases to select private attorneys, with some getting hundreds of cases a year, while others get none. Advocates worry that these lop-sided appointments contribute to the high number of mostly Black children from the county ending up in adult prisons — a subject The Marshall Project - Cleveland has thoroughly reported on in the past.

On the day of publication, our reporting was highlighted by advocates for strong youth defense at the regular meeting of the Ohio Public Defender’s Commission. At the meeting, local community groups and nonprofit organizations asked the Commission to investigate the Cuyahoga County Juvenile Court’s assigned-counsel system.

In response to our questions, the court said it will “modify” the system used to pick attorneys. There are no specifics yet.

State legislators sought to change how New York disciplines prison guards after we exposed how rarely officers get fired for abuse. Throughout 2023, we reported on how the corrections department in New York tried to fire hundreds of prison guards for abusing prisoners (or for covering it up), but only succeeded 10% of the time. Our work ran on the front page of The New York Times and in media outlets around the state, including the Albany Times Union. Thanks to our detailed, data-driven investigation, state legislators are trying to make it easier to discipline abusive guards.

A state senate bill filed in February 2024 would give the corrections commissioner — not private arbitrators — the final say on meting out staff discipline for serious misconduct. As part of our reporting, we found that three out of every four guards who appealed their firings got their jobs back through the current arbitration process. The bill sponsor called our investigation — which took more than two years of reporting and rigorous data analysis — a “stark picture of a staff disciplinary system that is essentially completely broken and ineffective.”

While the bill did not advance through the legislature, our story has continued to have impact. Following his death in a New York prison, the family of Robert Brooks filed a lawsuit that repeatedly cited The Marshall Project’s reporting on the culture of abuse within the New York state prison system. In December 2024, Brooks died after a brutal assault by corrections officers inside the medical unit at Marcy Correctional Facility, near Syracuse. In January 2025, Brooks’ family sued the officers and some state officials, frequently citing our reporting on the prevalence of abuse in the prison system and how difficult it is to hold officers to account. Later in January, The Albany Times-Union editorial board published an op-ed citing our work and demanding a new prison system that has more accountability and is safer for incarcerated people and staff.

Cleveland’s mayor promised to create an oversight committee after we reported on the lack of transparency in how police use surveillance equipment. In September 2022, The Marshall Project - Cleveland reported that Cleveland had spent millions on license plate readers and surveillance equipment in widespread use around the city. Local officials had refused to tell the public about how they were used. Activists raised concerns that police could feed the camera images into facial recognition software, leading to discriminatory policing practices, particularly in communities of color.

After we published our story, the mayor announced he was forming an advisory committee to examine how police technology affects communities of color. But despite this promise, the mayor’s administration has yet to form that committee.

In March 2024, we reported on the city’s slow efforts to create the committee. At the time, the mayor’s spokesperson responded to our report that meetings would be held in private and said they would instead be public.

An Oklahoma police department stopped forwarding cases involving medical marijuana for prosecution after we reported on how the state prosecutes women for using it while pregnant. In February 2024, we partnered with The Frontier and Kay NewsCow to examine whether it’s legal to use medical marijuana while pregnant in Oklahoma.

Medical marijuana is legal in Oklahoma. Amanda Aguilar had a doctor-approved license to use it, and it helped with severe morning sickness during her pregnancy. But a local prosecutor charged her with felony child neglect for using the drug while pregnant — a charge that has since been dismissed by a trial judge. Aguilar thought her ordeal was over, but the prosecutor appealed the judge’s decision.

Our investigation found that, in the past 10 years, the state has prosecuted 17 women — including Aguilar — for using marijuana while pregnant, even though they had a medical license to use it.

Soon after we published our investigation, the police department in Ponca City, Oklahoma said it was no longer forwarding cases involving medical marijuana for prosecution.

Our 2021 investigation helped restore federal benefits to foster children in at least 15 states and municipalities, and several other state legislatures are considering similar laws. Working with NPR, we revealed that almost every state was pocketing federal benefits meant for foster children. The story, which was a finalist for the 2022 Pulitzer Prize for National Reporting, prompted new legislation and policy in Nebraska, Connecticut, Illinois, California, Oregon, New York City, Philadelphia, Los Angeles, Washington, D.C. and Arizona.

According to a report from the Children's Advocacy Institute, as of April 2024, approximately half of the states have attempted, taken or are considering action to ensure proper access and use of foster youth’s federal benefits. A May 2024 feature in The New York Times covered the issue, highlighting that it was being taken up in Congress and statehouses and credited us for getting the story into the light.

We released our data and methodology on the website Observable to make it easily accessible; advocates, journalists and government officials from Massachusetts to Montana to Michigan have used our data. We also created a simple-to-use tool allowing people to check the policy in their state.

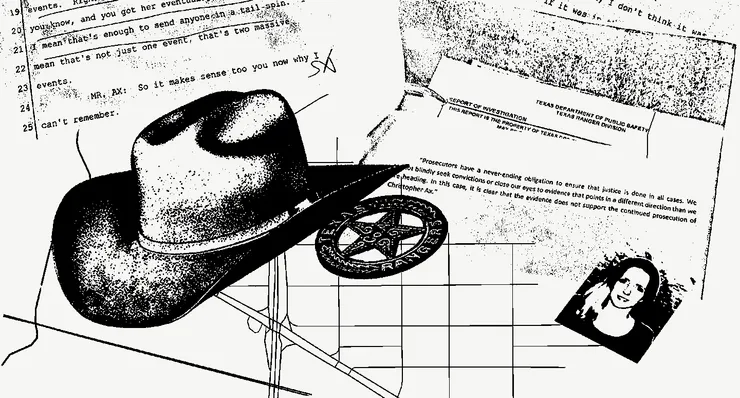

Following our investigation into a homicide detective’s methods, a Texas prisoner went free, and a new state law banned courtroom testimony based on “forensic hypnosis.” Larry Driskill, who was identified based on the technique, served seven years in prison for a murder he maintains he didn’t commit, but was released on parole in July 2022.

Driskill had been convicted after detectives hypnotized a key witness and used “aging” technology on a composite sketch. His lawyers say The Marshall Project’s coverage was a key factor in the state parole board’s decision to free him.

Our story, “Anatomy of a Murder Confession,” revealed the coercive interrogation techniques used by Texas Ranger James Holland, who was among the most famous cold-case-solvers in the United States.

Our reporter made records requests to more than a dozen government agencies and linked Holland to 25 cases. We obtained 30 hours of audio and video — along with thousands of pages of reports and court testimony — from interrogations across Holland’s career. Somethin’ Else, a subsidiary of Sony Entertainment, released “Just Say You’re Sorry” in May 2023 based on our reporting about Holland and Driskill. As of November 2023, episodes of the podcast have been downloaded 860,000 times.

The podcast was based on our investigation in partnership with the Dallas Morning News. Texas was one of the last states in the country to use the tactic of forensic hypnosis. Supporters said it could help witnesses better recall details of crimes, but psychologists warned it could lead to arrests of innocent suspects.

After we published a story on “driving while Black” in the Cleveland suburb of Bratenahl, the police department started issuing fewer tickets overall, and recording race data in traffic stops. Our November 2022 investigation, co-published with News 5 Cleveland, estimated that at least 60% of those ticketed in Bratenahl were Black, even though 75% of Bratenahl residents are White. These findings were extremely difficult to piece together because Bratenahl police were not regularly recording the race of the drivers whom they stopped. Just one month after that story published, we noticed that Bratenahl officers issued significantly fewer citations.

Now, at least the reporting of the problem has gotten better. In February 2024, new data showed that 69% of all tickets since February 2023 went to Black drivers. Village officials say they hope more police anti-bias training and record-keeping will solve the problem. By forcing transparency in this data, our reporting has made it easier for the public to hold the police department accountable, and it has provided concrete evidence for what many Black Clevelanders call the “Bratenahl Tax.”

At the state level, an Ohio lawmaker vowed to introduce legislation that requires police agencies across the state to record the race of the people they stop for traffic violations.

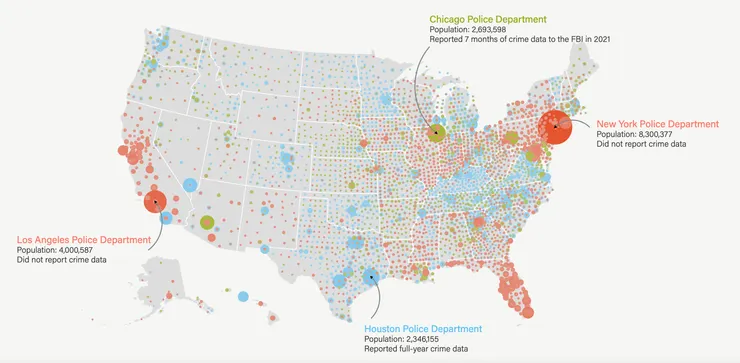

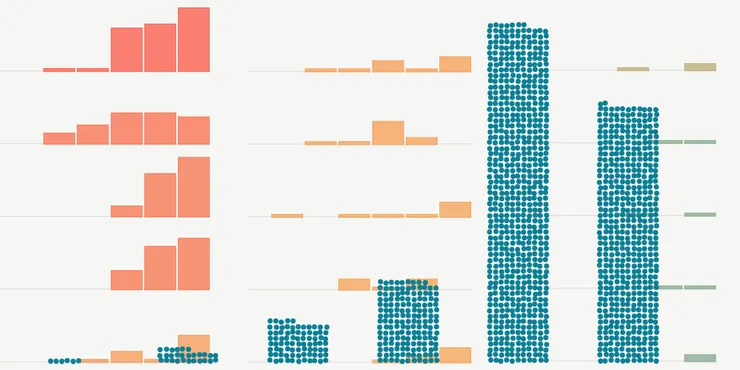

Our June 2022 investigation into FBI crime statistics generated dozens of local stories and put pressure on local law enforcement to improve their crime accounting to the FBI. We found that nearly 40% of police departments had failed to report their 2021 crime statistics to the federal government. We then worked extensively with dozens of local reporters from the news outlet Axios, showing them how to mine our database for insights — resulting in no fewer than 20 local stories on this topic, reaching nearly a million additional readers. NBC 4 in Columbus, Ohio, even got a local sheriff to admit on camera that The Marshall Project’s story “is going to cause us internally to take a look at our process, and we’ll be addressing that in the very near future.”

Our video series, Inside Story, serves an audience that no other major media outlet has treated as a priority: people in prison, and their families and loved ones. On YouTube, the trailers and eight episodes of Season One of Inside Story have collectively been viewed more than 1.4 million times, making this one of the most widely-consumed news products The Marshall Project has ever published. On The Marshall Project’s Instagram, the series’ video clips have been viewed more than 385,000 times.

Millions more were exposed to Inside Story via media coverage about the series. The New York Times published an extensive profile on the day of our launch, and the show’s host, Lawrence Bartley, appeared on ABC News Live Prime, CBS Mornings, NPR’s All Things Considered and Cleveland’s Jimmy Malone Show.

For obvious reasons, it’s much more difficult to track the size of our audience inside prisons. The series is distributed to roughly 750 prisons and jails via tablet companies Edovo, APDS and PayTel, Ameelio, and on closed-circuit prison television in Illinois and Colorado. Currently, our estimated total audience behind bars is approximately 273,100 incarcerated individuals based on the sum of all the tablets deployed by the tablet companies, and the number of people incarcerated across Illinois and Colorado state prisons.

We do have anecdotal and qualitative feedback from incarcerated viewers of the series:

“You beat the rumor mill to a bloody pulp. Dudes were waiting on some sort of truth in this joint… Keep up the good work. Fantastic bro.” — James, incarcerated in New York

“It feels good to see Inside Story talk about the truth of what it is to be incarcerated. We’re fortunate to get this series in our N.C. prisons.” — Cadell, incarcerated in North Carolina

“I bawled my eyes out after watching ‘I wonder if they know my son is loved’ because I’ve been here. That feeling of helplessness, of utter fear for your child, who this system views as an adult.” — Ari, parent of an incarcerated person

Our investigation into rampant violence prompted the shutdown of the Special Management Unit at Thomson prison in Illinois, and a decision six months later to convert Thomson to a minimum security prison. The federal Bureau of Prisons made the decision to close the unit in February 2023, months after The Marshall Project and NPR revealed how many people were being kept in “double solitary” confinement in Thomson — and how often deadly violence resulted.

Immediately after our story was published, Sens. Dick Durbin and Tammy Duckworth and Rep. Cheri Bustos of Illinois, demanded the Inspector General of the Justice Department investigate claims that staff purposefully housed prisoners with people they knew would be violent, and subjected them to painful restraints for hours, or sometimes days.

In Senate floor testimony, Durbin cited our investigation while slamming the Bureau of Prisons for mismanagement and calling for a new “reform-minded” leader for the BOP. That new leader, Colette Peters, announced the closure of the Special Management Unit in February 2023. A Bureau of Prisons spokesperson said that the bureau had “recently identified significant concerns with respect to institutional culture and compliance with B.O.P. policies” at the high-security facility. After we published a follow-up story about ongoing abuse, for which we asked Sen. Durbin for comment, he released a statement calling for the Special Management Unit to be abolished. In August 2023, Sens. Durbin and Duckworth announced that the federal Thompson prison would be converted to a minimum security prison.

The ACLU, the National Religious Campaign Against Torture and other advocacy groups urged the Inspector General to shut down Thomson and ban solitary confinement in federal prisons. Other media covered the issue, helping to amplify our reporting.

In November 2023, The Marshall Project and NPR published another shocking scoop, this time detailing prisoners’ allegations of a plot by corrections officers to bribe them to attack the warden and one of his captains. The former warden went on the record with The Marshall Project, building on our earlier reporting and revealing even more shocking details about the abuse inside.

Texas rolled back a policy preventing books from reaching incarcerated people after we began reporting on drug smuggling policies that act as de-facto book bans. Our database of banned books makes it easy to look up which books are banned from prisons in your state, and dozens of other media outlets used it to report stories of their own. WRAL News in North Carolina filed their own Freedom of Information Act request with state corrections officials to find out more; a TV station in Austin used our database to make a local version just for Texas; a Reddit group with nearly 3,000 members, r/bannedbooks, included our database in their carefully curated resource page.

Keri Blakinger, a former Marshall Project reporter who now works for the Los Angeles Times, appealed Florida’s decision to ban her memoir, “Corrections in Ink.” Officials there had claimed that the book is “dangerously inflammatory” and “presents a threat to the security, order, or rehabilitative objectives of the correctional system or the safety of any person.”

Blakinger began an appeal process that ended up taking five months. A statewide Literature Review Committee twice upheld the decision to ban the book, despite letters of support from the ACLU, PEN America, and others. Finally, the matter went before the head of the state's prison system, who overturned the ban in February 2023.

In October 2023, the Texas Department of Criminal Justice rolled back its policy preventing books-to-prisoner programs from sending literature inside, after we began asking questions and before our story was even published. They acknowledged they did this after receiving our questions.

Our reporting often helps people get new and better lawyers. Shuranda Williams, who was facing a potential life-without-parole sentence in Texas, had spent more than a year in the county jail without a bail hearing. Her court-appointed lawyer hadn’t filed any motions on her behalf; he wouldn’t even return her calls. After we revealed how frequently people in her position lack an effective lawyer, she was appointed new counsel and her bond was reduced, allowing her to get out of jail. Finally, prosecutors dropped the charges against her in June 2022.

Tiffany Woods also got new legal representation in November 2022 thanks to our reporting. Tiffany was a young mother whose baby died of malnourishment in the months after Hurricane Katrina. Prosecutors decided her child’s death was murder in the second degree, which doesn’t require proof that anyone intended to harm the baby. Tiffany was found guilty of the charge and sentenced to life in prison without parole. With a new legal team in place, Tiffany now has a pardon hearing scheduled.

Ashley Traister got full custody of her older daughter restored in June 2023, after the publication of our 2022 investigation into women being prosecuted for drugs. Traister was the lead example in our story about district attorneys criminally charging women who had miscarriages or stillbirths and tested positive for drugs — even if there was no proof that the drugs were the cause. After our story was co-published with the Washington Post, AL.com, and The Frontier, the Oklahoma district attorney who was pursuing Traister dropped all remaining charges and allowed her to serve probation on the charge of child neglect. He later said he was unaware that she was a victim of domestic violence. Four months later, she got full custody rights to her daughter, Lily.

Cherie Mason, who has four daughters and was originally sentenced to 12 years for manslaughter for a stillbirth in 2017, is now scheduled to be released from prison early. She got a new legal team as a result of our reporting, which featured her case, and the district attorney agreed to modify her sentence. She will now be released about five years ahead of schedule.

Meanwhile, a coalition of civil and human rights organizations filed a formal letter in 2022 on extreme sentences that cited two stories from The Marshall Project. The letter urged United Nations special rapporteurs to declare the United States’ longstanding practice of subjecting people to life without parole and extreme sentences as “cruel, racially discriminatory” and “an arbitrary deprivation of liberty.” The complaint cites two Marshall Project stories, one from 2018 and one from 2021 on life without parole in Florida.

After we published several stories with The Frontier, Oklahoma lawmakers held a study session at the Capitol in September 2023 about criminal charges related to substance use during pregnancy.

Our story about the “thin blue line” American flag was cited multiple times in a court decision involving bailiffs who wore COVID masks adorned with the flag in court. The controversial version of the U.S. flag, used to signal solidarity with police, has been criticized as a symbol of white supremacy. The Maryland Court of Appeals’ September 2023 decision to overturn a conviction relied heavily on our history and analysis of the image in declaring the masks prejudicial to the right to a fair trial.

The state of Mississippi demanded a huge refund from the country’s third-largest prison company following our investigation into “ghost workers.” Our 2020 investigation revealed that a private company called MTC charged the state of Mississippi for vacant prison guard positions that, by contract, had to be filled at all times due to security concerns. This practice made more money for MTC while making prisons more dangerous for staff and incarcerated people. Our investigation, which was co-published with multiple papers across the state, revealed that MTC had collected an estimated $8 million in taxpayer money from vacant security positions at the three prisons it managed.

Corrections Commissioner Burl Cain responded by kicking MTC out of the Marshall County Correctional Facility. In 2022, the state’s auditor demanded that MTC pay nearly $2 million for improperly billing the state for vacant shifts at the Marshall County Correctional Facility; MTC ended up paying $787,000 to the state for that. In 2023, MTC wrote another check, this time for $5.125 million, to the state of Mississippi — one of the largest checks in recent history — for short-staffing key security positions at two other prisons, Wilkinson County Correctional Facility and East Mississippi Correctional Facility.

State Auditor Shad White said, “We will continue investigating the MTC matter to ensure the amount the company remitted is the full amount they owe the people…Every penny must be accounted for.”

In order to conduct this investigation, The Marshall Project sued the state’s corrections department for violations of the public records act. In court, prison administrators admitted they couldn’t find more than half of MTC's contractually mandated safety reports. As a result of the lawsuit, representatives from the prison system said that going forward, they will ensure the reports, which detail attacks on prisoners and guards and other policy violations, are written and filed as required.

Our 2022 reporting on “constitutional sheriffs” helped prompt Texas to prevent an extremist group from teaching courses to law enforcement. The Texas agency overseeing police training decided to bar the Constitutional Sheriffs and Peace Officers Association (CSPOA) from teaching continuing education classes. The CSPOA believes sheriffs are more powerful in their counties than any state or federal agency. In a memo, the Texas Commission on Law Enforcement said that the decision to ban the group from teaching was spurred in part by public information requests from the media. We made one of these requests in 2021, and our 2022 story on the CSPOA appeared in multiple media outlets, including NPR’s All Things Considered and Here & Now, Wisconsin Public Radio, Radio France, and the podcasts Vox’s Today Explained and The Daily Beast’s Fever Dreams. The series was also cited by The New York Times, The Independent, WNYC’s The Takeaway, Oregon Public Broadcasting, Truthout, and Investigate West.

Our April 2022 investigation with The New York Times into the political messaging spread by Crime Stoppers of Houston contributed to an investigation into the organization. The organization has traditionally been a nonpartisan nonprofit, gleaning crime information from the public via its tip line. Our reporting revealed the organization took millions in state grants backed by Republican Gov. Greg Abbott, and began publicly blaming judges appointed by Democrats for a rise in crime.

Local media amplified our story, with The Texas Standard doing an audio segment and the Houston Chronicle probing deeper into the issue with its editorial, “Can we still trust Crime Stoppers?” Meanwhile, Harris County Commissioner Rodney Ellis instructed the county auditor to investigate funds the county had given to Crime Stoppers of Houston, and how they were used. Ellis praised our reporting and encouraged people not to “shy away from fact-based journalism.”

The audit was released in September 2022 and showed the county gave about $7.2 million to Crime Stoppers of Houston over the last decade. However, Ellis said the audit was limited in scope because “there were some challenges with getting the information for the audit from Crime Stoppers.”

Spurred by our joint 2021 investigation into immigrant workers, The New Bedford Light started a weekly feature to serve Spanish-speaking audiences. Our story with The Light uncovered just how many immigrant workers had been left out of COVID-19 relief payments. The immigrants who work in seafood-processing plants in New Bedford, a city on the south coast of Massachusetts, had been left out of thousands of dollars of COVID-19 relief payments for essential workers. After working with us on this story, The New Bedford Light started a new weekly feature in Spanish, NOTICIAS-NB. They spoke with a woman who, after our story was published, received $500 in COVID-19 relief compensation from the state for working through the pandemic.

A May 2022 Marshall Project investigation was heavily cited in a lawsuit by the family of a man killed by a fire at a Texas prison. Jacinto De La Garza spent his last breaths gasping for air while the smoke thickened in his cell, and his neighbors shouted for help that never came. The Marshall Project initially began reporting on Texas prison fires in 2020. Our report, co-published with the Houston Chronicle, was cited by De La Garza’s family in their lawsuit against the Texas Department of Criminal Justice for failing to have working fire alarms in prisons.

Louisiana enacted the state’s first law restricting the use of solitary confinement in juvenile facilities after our investigation uncovered abuses. Our reporting with ProPublica and NBC News revealed that the Acadiana Center for Youth at St. Martinville held teens as young as 14 in solitary confinement virtually around the clock for weeks.

Louisiana’s largest newspaper, The Advocate, reprinted our story in its local editions in Baton Rouge, Acadiana and New Orleans. The paper also published stinging editorials condemning the conditions and made its own request for state records to write a follow-up story to our investigation.

Advocates, including the Equal Justice Initiative and Juvenile Justice Exchange, shared the story with their national audiences. And a local group called Families and Friends of Louisiana’s Incarcerated Children incorporated our report in statements they sent to local media and policymakers.

The Louisiana state legislature held two hearings, and the bill limiting the use of solitary confinement for children passed both houses by large margins. The law restricting solitary confinement went into effect in August 2022, limiting young people to no more than eight hours in isolation unless they continue to pose a physical threat to themselves or others. Children must receive a mental health check within the first hours of being placed in solitary confinement, and their parents or guardians must be notified.

Our story investigating the deadly world of private prisoner transport sparked an investigation by the federal Department of Justice under Attorney General Loretta Lynch. Every year, tens of thousands of Americans are packed into private vans and taken on circuitous, often harrowing, journeys to other states to face charges. Our reporters spent seven months investigating the industry’s on-board deaths, sexual assaults, accidents and escapes. Our story sparked an investigation by the federal Department of Justice. In a rare instance of cross-administration continuity, lawyers in the Jeff Sessions Justice Department opened an investigation in the summer of 2017 into allegations of abuse by the largest prison transport company we profiled. Our story also helped other reporters pursue their own investigations locally — like the one in Lewiston, Maine, whose work has gotten three district attorneys to forswear the use of private vans.

Our four-part series questioning the success of Texas’s Operation Lone Star spurred advocacy on the controversial border security initiative. Our 2022 investigation revealed that many arrests touted as “border security” in fact occurred hundreds of miles from the border. Sometimes U.S. citizens, not undocumented migrants, were arrested. Two weeks after we published, 15 public defense offices called on the U.S. Department of Justice to investigate the border program for making arrests based on race and national origin, noting that more than 3,000 people have been arrested — the majority of whom are Latino and Black men.

Our story kicked up a media storm. The Dallas Morning News published an editorial chastising the state’s use of “dirty metrics” to bolster the program, while the Austin American-Statesman’s editorial called the border mission “long on hype, short on proof.” Our reporters conducted local radio interviews in English and Spanish, including Texas Public Radio, Houston Public Radio, City Limits en Español, and Radio Bilingue. Our investigation was also published in Spanish with Al Dia Dallas. At the national level, CBS Mornings ran “Inside Operation Lone Star,” a lengthy segment questioning the controversial program’s effectiveness, and The Washington Post also used our work in a major story.

Our reporting on voting rights prompted Colorado officials to change its voter information form – even before the story was published. The Marshall Project got a tip from a mother who was confused by the forms her son received after he was released from prison on parole. The forms said he was ineligible to vote, even though the Colorado state legislature had reversed its ban in 2019, restoring voting rights to 11,000 people on parole. The day before our article was co-published with the Colorado Sun in March 2022, the Colorado Secretary of State notified us that his office had updated its erroneous voter information form.

Two of our reporters subsequently appeared on Inside Wire, the first statewide prison radio station in the U.S. Their interview aired in all facilities run by the Colorado Department of Corrections, which reaches up to 14,000 incarcerated listeners, hundreds of CDOC staff, and listeners on the outside.

Our print publication for incarcerated audiences, News Inside, inspired Alex Valentine to start a peer-supported literacy program for other incarcerated people. Valentine received a copy of News Inside at his college program in prison in California, and started the literacy program after transferring to a lower-security facility. He told The Marshall Project in 2022 that he uses issues of News Inside to teach other incarcerated people to read.

Our deep dive into Cuyahoga County’s criminal court system shook up its 34 judges. The multipart series Testify, released in 2022, revealed how some of Cuyahoga’s judges almost never send defendants to prison for charges like theft and drug possession, while others incarcerate one in three defendants. Meanwhile, 30% of the county’s residents are Black, but 75% of the people convicted in Cuyahoga courts and sent to state prison are Black. Days after our investigation was published, the county’s judges held an in-person meeting and discussed our findings, and The Greater Cleveland Congregations — a consortium of local faith groups from across Cuyahoga County — organized a community forum for residents to meet with candidates seeking election to the judicial bench. Testify appeared in at least seven different local media outlets in Cleveland, including the local NPR affiliate IdeaStream and a Black community radio station serving the Kinsman neighborhood and surroundings.

After our investigation on states charging parents for the cost of their child's incarceration, two states changed their policies. Nineteen states charge parents for the cost of their kids’ incarceration, even if that child is later proven innocent — sometimes as much as $1,000 a month from some of the nation’s poorest families. Our March 2017 story, published on the front page of The Washington Post, highlighted this cruel practice with a focus on Philadelphia. Hours after publication, Philadelphia announced it was abandoning the policy, effective immediately. Months later, California followed suit.

Democratic U.S. Sen. Brian Schatz of Hawaii filed a bill to improve compassionate release from federal prisons using data from our 2020 story. Allowing early parole for sick or elderly prisoners became a big issue during the pandemic, and our reporting showed that even fewer requests for compassionate release from federal prisons were being approved during the pandemic than before. Of the 10,940 federal prisoners who applied for compassionate release from March 2020 through May 2020, wardens approved a mere 156. Schatz was joined by Republican Sen. Mike Lee of Utah, demonstrating how criminal justice data can move politicians on both sides of the aisle.

Meanwhile, our investigation was cited in a 2020 federal court ruling allowing district courts to reduce sentences for incarcerated people in “extraordinary and compelling” circumstances — essentially, to counteract the Bureau of Prison’s reluctance.

Months after our investigation, the Department of Justice ordered agents with the U.S. Marshals to wear body cameras when making a pre-planned arrest or executing a search warrant. Our reporting examined the U.S. Marshals, its high shooting rates, and several of the agency’s outdated standards. We discovered that the U.S. Marshals Service was responsible for more shootings per year — 31 on average — than major police departments like Houston and Philadelphia. This record of shootings would likely have generated outrage in an American city, but U.S. Marshals were not being held accountable.

Our reporting was also used by other media when shootings related to the U.S. Marshals occurred in their communities. After a March 2021 shooting in Phoenix, an editor at KPNX-TV ran our story, saying, “It was a piece of fantastic journalism and is sadly relevant tonight.” Queen City Nerve, an alternative weekly in Charlotte, North Carolina, republished our story in April 2021 after a shooting death involving Marshals occurred there.

Our reporting has also helped inspire a whole new advocacy group. The U.S. Marshal’s Accountability Project says it aims to “hold the U.S. Marshal’s Office accountable for the excessive force used by many of its ‘Violent Fugitive Task Forces’ around the country.”

Several Texas prisons were renamed following our story about how many of them take their names from racists, Confederates, plantations, segregationists and owners of slaves. Our 2020 story spurred the Texas Department of Criminal Justice to act. For example, one of the renamed Texas prisons bore the name of a former slave plantation: The Darrington Unit of the Texas Department of Corrections was previously a plantation that produced cotton and sugar cane with slave labor. John Darrington of Alabama bought it for $3,028 in 1835, but was an absentee landlord, according to the Texas Department of Criminal Justice. As the property was bought and sold over the years, it retained the Darrington name, even when the land was sold to the state of Texas. The unit has been renamed the Memorial Unit.

A coalition of 142 organizations submitted a letter citing our 2021 reporting to Congress, the White House and the attorney general, urging them to change how fentanyl crimes are prosecuted. In May 2021, President Biden quietly extended a policy that critics called a betrayal of his campaign promise to end mandatory minimum sentences. The issue concerned “class-wide scheduling of fentanyl analogues,” or drugs that are similar molecularly to fentanyl, but not exactly the same. The coalition, led by the Drug Policy Alliance and The Leadership Conference on Civil and Human Rights, filed a letter protesting the policy, which could make it easier to punish low-level drug dealers and put them in prison for longer periods with less proof than is usually required. The coalition called out the policy for the way it “leans on law enforcement, not evidence-based public health solutions, to solve the overdose epidemic.”

An investigation on Tennessee's “safekeeper” law led directly to the first reforms to the law in 150 years. Pretrial solitary confinement is now banned for incarcerated youth and pregnant people. “Too Sick for Jail — But Not for Solitary” exposed the devastating toll of the law, which allowed people with mental illness, or who are pregnant, ailing or youth to be locked in isolation in prison while awaiting trial.

Our 2021 data investigation prompted a legislative resolution in Nebraska to study voting among formerly incarcerated people. No more than 1 in 4 formerly incarcerated people were registered to vote in time for the 2020 election, according to our data investigation in four battleground states that had legally restored the right to vote to these communities. This reporting informed the legislative resolution, which acknowledged the “data and system errors” that “impermissibly disenfranchised eligible voters from participation in the election process.”

Three prison guards pleaded guilty to misconduct the day after our investigation into abuse at New York’s Attica prison was published on the front page of The New York Times. The U.S. Department of Justice quickly launched an investigation; and prison officials began installing 1,875 cameras and nearly 1,000 microphones around the facility. A subsequent feature by one of our incarcerated contributing writers, who has lived at Attica, described the effect our story has had there. Violent incidents at the prison dropped by nearly 80%, as guards faced an “unprecedented level of transparency and accountability.”

Our investigation was nominated for a Pulitzer Prize.

The Ohio state legislature expanded the state’s victim compensation funds to people with felony convictions in March 2022. State bans on financial help for crime victims with previous criminal histories were the subject of our 2018 investigation, which appeared in media nationwide via USA Today and the radio network Reveal. As part of their lobbying for the bill, advocates cited our investigation, which found that Black crime victims and their families were disproportionately prevented from receiving money from the state — to pay for the funeral of a loved one who is murdered, for example — because the victim had a felony conviction, even a very old one, on their record. Louisiana lawmakers similarly expanded eligibility for compensation to victims with previous convictions in 2019, shortly after our story was published.

One listener set up a scholarship fund for high school students after hearing our 2018 reporting with This American Life on a GED program for kids in a violent adult jail in New Orleans. The listener, a man from Elgin, Illinois, said he heard the story while out cycling in his neighborhood and it “tore [him] apart.” He told NPR, “As I had plenty of thinking time on the bike, I got back home and told my wife that we are going to call the local Boys and Girls Club and set up a scholarship fund so that one kid a year who would otherwise be financially unable to go to college at all, even with the many scholarships the school offers, could do it.”

Our 12-part series on the life-altering injuries caused by police dog bites spurred policy change in several municipalities. The data-driven investigation won the 2021 Pulitzer Prize for National Reporting, shared with our media partners AL.com, IndyStar and the Invisible Institute.

Police dogs bite thousands of people every year in the United States, leading to devastating injuries — and sometimes death. Our reporters identified and tracked individual cases, and eventually built a nationwide database of more than 150 severe incidents. Days after our first story was published in October 2020, the Indianapolis police publicly promised significant changes in its use of dogs. Indianapolis had the highest rate of dog bites among major cities.

Indianapolis city councilors relied on our reporting in pressing the police chief for answers on what’s driving racial disparities in police dog bites in their city.

Meanwhile, just hours after our story ran on the front page of the Baton Rouge Advocate, Mayor Sharon Broome directed the police chief to stop using dogs on juvenile suspects “for mere flight,” adding, “I embrace this journalistic work in our process to continue improving our department.” States from Massachusetts to Washington also have reviewed their use of police dogs; and our stories prompted a national police think tank to begin work on national guidelines for K-9 units.

Other media also used our findings to cover the issue in their communities. A television station in Tampa, Florida, for example, produced an investigation into “the consequences when police dogs disobey their handlers.” The East Bay Times tracked the 73 police dog bites that plagued the city of Richmond, California. The Reporters Committee for Freedom of the Press filed FOIA requests for the federal Department of Justice guidelines on police use of dogs.

The Mississippi auditor’s office released a blistering report that confirmed findings from The Marshall Project’s 2020 investigation into the state’s “restitution centers.” These modern-day debtors’ prisons compel incarcerated people to work for private companies to pay off fees and fines; they are sentenced for an amount of money rather than a period of time. The audit confirmed that the Department of Corrections was not informing people when they had repaid their debt.

The Marshall Project’s 2020 story of a woman who was struck from a jury pool helped advocates push for a bill to discourage juror discrimination. Crishala Reed was promptly struck from a jury pool after saying she supported Black Lives Matter. The MacArthur Justice Center cited our story and quoted from our interview with the juror in their amicus brief in the case, and advocates used our reporting in their push for a bill in California to prohibit juror discrimination. Once the legislation landed on the governor’s desk and was signed in October 2020, one of the bill’s main proponents wrote to one of our reporters to say thank you “for helping to tell this story and mak[ing] this result possible.”

Our weekly COVID-19 updates became the “go-to” resource for other media organizations in 2020, who cited us more than 670 times in their own pandemic coverage. Our reporters contacted prison authorities in all 50 states and the federal system to gather weekly updates on the number of people inside prisons who tested positive, and those who had died. We eventually joined forces with The Associated Press on the data collection, which ensured that our findings were distributed to journalists in hundreds of local newsrooms around the country.

The Washington State Department of Corrections used our data on their website to track COVID-19 cases across the country. The Iowa Department of Corrections began linking to our tracker in its press releases.

Sens. Elizabeth Warren and Cory Booker, along with Rep. Ted Deutch, sent letters to both the United States Marshals Service and Prisoner Transportation Services, urging them to perform COVID testing before transferring incarcerated people between facilities. Their letters cited our reporting, as well as our investigation with VICE News into how the U.S. Marshals Service helped spread COVID-19 throughout the federal prison system.

Sen. Amy Klobuchar used our story in a letter to Attorney General William Barr, while several others, including Sen. Cory Booker and Rep. Ayana Pressley, relied on our numbers in a letter to governors of five hard-hit states, urging them to release people from prison who were over 50 or had pre-existing health conditions.

A prison work program in North Carolina got shut down after our March 2020 report revealed how it might be spreading COVID. Published in partnership with the News & Observer in Raleigh and Charlotte, our investigation revealed that the state of North Carolina was still allowing hundreds of incarcerated people to leave prisons to work for local industries such as chicken-processing plants, potentially bringing COVID-19 back with them at the end of the day. State corrections officials had already shut down family visits and restricted educational and other programs in prisons because of the pandemic. But they were still sending incarcerated people out of the prisons to work. “The Division of Prisons is sensitive to the business needs of participating employers,” a spokesman for the department said. After our story with the News & Observer in Raleigh and Charlotte, the state shut the program down.

After our 2020 story on COVID-19 in New Orleans’ crowded jails ran in every Gannett paper in Louisiana, the city’s jail population began dropping more quickly. As COVID-19 was sweeping through New Orleans, we reported how local officials were painfully slow to reduce the jail population of 900 people. Less than a week after our story’s publication, the jail population had shrunk to 763 people — still too high, many advocates felt, but an improvement. We also exposed how court monitors were being shut out of courtroom Zoom proceedings in places like New Orleans. Within a day, one district court judge had provided a link to monitors who could then observe the proceedings in her courtroom.

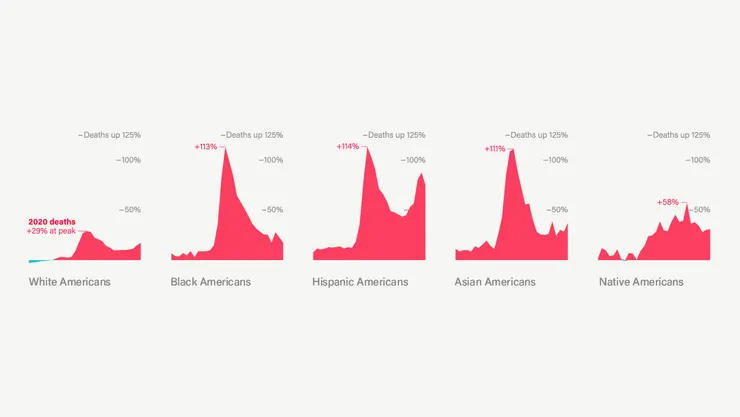

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention released data about excess COVID-19 deaths by race after we pursued that information for several months via public records requests. Our 2020 story visualized the striking data on racial disparities in COVID deaths. Additionally, a letter signed by 93 members of Congress cited our analysis, and argued for more robust and accurate collection of excess mortality statistics by the CDC.

The Marshall Project’s 2020 reporting on prison meals during the COVID-19 lockdown helped bring a change to quality control procedures. Our reporting revealed that the pandemic had made meals even more disgusting in 40 Texas prisons during the COVID-19 lockdown. Paper bags of cold, mushy food were coming at strange hours—sometimes 3 a.m., then not again till 4 p.m., without a green vegetable in sight. After our story ran in Houston and San Antonio newspapers, lawmakers reached out to prison officials, who told families of the incarcerated that they would revise quality control procedures. Days later, people living in one prison reported a change: They’d received hot meals at last. Prison officials told families of the incarcerated that vegetables, real milk, and fresh fruit had been ordered.

Our 2020 investigation into children being placed in short-term foster care created change before it was even published. The Marshall Project worked on an exposé about these “short-stayers”— children who are removed from their homes, often in the dead of night, and placed in foster care for ten days or less. Experts say the trauma these children experience can be akin to that of a kidnapping. While reporting this story in New Mexico, which has the highest rate of “short-stayers” in the country, our reporter heard repeatedly that top officials at the state’s child welfare agency were worried his article would embarrass them. Before our story was published, child welfare agencies reached a formal agreement with the Albuquerque police department to reduce the number of “forced removals” of children, and the state started providing families with financial support and other resources. As a result, “short-stay” removals in New Mexico dropped by more than half. After months of further studying the problem, the New Mexico legislature sent a report to the child welfare agency outlining steps for fixing the problem, requiring the agency implement it within one month.

The Marshall Project’s 2018 story about a wrongful death case in a New York prison helped the victim's family find a lawyer, who won a record-setting settlement for the family. Karl Taylor, incarcerated at Sullivan Correctional Facility and struggling with mental illness, was ordered to clean his cell one day in April 2015. Later that day, Taylor died after an altercation with corrections officers, and a contributing writer for The Marshall Project followed the case closely as his sister sued the state for damages. He even gave her the phone number of a prison advocate, who found her a lawyer — who won a record settlement of $5 million for the family. Terms of the agreement included an unprecedented pledge by officials to install video cameras and microphones throughout Sullivan prison. “I am hoping they can save someone else’s life,” said Taylor’s sister. When similar measures were taken at Attica prison, also in the wake of our 2015 investigation, levels of violence dropped dramatically.

Following our 2018 story with the New York Times, the North Carolina State Bar suspended the law license of a lawyer who stole from two clients with intellectual disabilities. Half-brothers Henry McCollum and Leon Brown spent three decades in prison before being declared innocent. Our reporting revealed how lawyer Patrick Megaro repeatedly pocketed his clients’ money and set them up with predatory loans. The State Bar found that Megaro put his own financial self-interest above those of his former clients, who are legally incompetent to manage their own affairs. Megaro was asked to repay the men $250,000 before he could request his license back. Additionally, a jury in a North Carolina federal civil rights case awarded $75 million to the two brothers for their wrongful convictions.

Our Pulitzer Prize-winning investigation about a young woman who reported being sexually assaulted, only to be disbelieved by police as the perpetrator went on to attack many other women, has been used for training purposes. Years later, two relentless female detectives in Colorado solved the case, revealing that Marie had been telling the truth all along. The story reached an audience of millions online, through its adaptation on This American Life and via the hit Netflix series Unbelievable. It was used in police academies, emergency rooms, and universities to train police and first responders on how to respond with greater understanding to survivors of sexual assault.

Our 2016 story inspired a new alliance of 37 human rights organizations dedicated to improving conditions at the federal penitentiary we profiled. What’s worse than being in solitary confinement? Being in a solitary cell with another person for 23 hours a day — with often violent results. Reporter Christie Thompson teamed up with National Public Radio to expose the abuse that incarcerated people suffer when they refuse to accept a cellmate. Our story inspired an alliance of 37 human rights organizations dedicated to improving conditions at the penitentiary we profiled.