The Marshall Project receives about 3,000 letters a year from people who are incarcerated, their families and their support networks. For the past year, I’ve been part of a team opening the mail and reading through their stories.

Some letters are deeply emotional — like one from a man in Florida, newly diagnosed with liver cancer, pleading for the medical treatment he’s been denied. Others are lighter, like the artwork sent to hang on our office walls, or a simple thank-you for covering an issue that resonates with people behind bars. Some letters are requests for legal help and other resources. Many are from readers writing to request their own copy of our award-winning magazine for people in prisons and jails: News Inside.

No matter the content, the letters often convey a sense of urgency. Many people tell us they’re writing to us because they have nowhere else to turn. They describe facing challenges that require immediate action: untreated physical and mental health issues, overcrowded prisons and constant lockdowns, inedible food.

Our mission at The Marshall Project is to spotlight the criminal justice system, exposing abuse, harm and wrongdoing through our journalism. Even if the letters don’t prompt an investigation, they illuminate the impact of the system on the people ensnared in it. Here is a snapshot of what I’ve found.

The real story of people in prison unfolds long after sentencing.

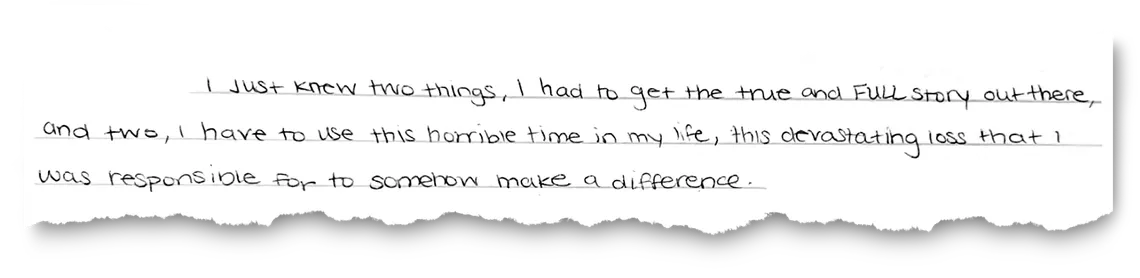

In October, I read a letter from a young woman serving 19-to-life for the “devastating loss” of a childhood friend. She wrote about the regret she felt after killing her friend in a car crash following a night of drinking. And she shared her desire to use her time in prison to “make a difference.”

Local news outlets covered the crash and her court case in detail. During the trial, her lawyers advised her not to speak. The media interest in her story ended the day a judge handed down her sentence. She never got a chance to tell her side of the story.

Many people write to us to share their understanding of the path that led them to prison. The letters don’t read like excuses. Many are able to connect the dots between the harm they inflicted and the harms they endured. Ultimately, many of the people who write this kind of letter also share their intention to commit themselves to a new path. Their letters tell a fuller story of their lives.

The young woman’s letter raises important questions for me as a journalist. She has been incarcerated for nearly four years. She is hopeful today, but what will nearly two decades in the system do to her? Will her time in prison allow her to fulfill her promise to make a difference?

Seeking justice, incarcerated people become their own lawyers.

Judges rarely take a second look at sentencing decisions. Only 12 states and the District of Columbia have policies that allow judges to reexamine lengthy sentences imposed decades ago. The process is often procedurally and politically fraught.

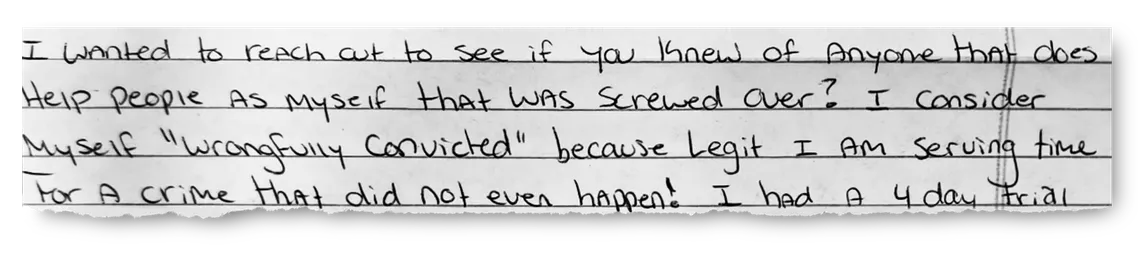

So, many people hope that publicizing their case might lead to a shift in public opinion, or some kind of legal breakthrough or action on their behalf. Some write out their entire life stories by hand, covering decades and sparing no detail. Others send meticulously organized, thick packets of documents, evidence and court transcripts — all in an attempt to prove their innocence or receive a different outcome. (As a news organization, we don’t take on legal cases or advocate for individuals.)

Legal language is a carefully wielded tool in prison. Incarcerated writers use legal terms like “due process,” “exculpatory evidence” and “habeas corpus.” Many have had to become their own lawyers, shaping arguments and presenting evidence in hopes that their cases will be taken seriously.

It is impossible to know how many of their cases have merit. Still, the letters reveal the scale of the problem. As new research made clear that long sentences do not improve public safety, many criminal justice reformers campaigned for more pathways out of prison. At the same time, exonerations are on the rise, revealing that mistakes (and malice) are a facet of the justice system.

Creating art becomes a way to reclaim time otherwise lost to restrictions.

We’ve received art in nearly every form: personal essays, excerpts from novels in progress, poems, pencil drawings, paintings and experimental, stream-of-consciousness writing (typed and handwritten).

People in prison often describe their artwork as a “thoughtful” use of their time. It is a way to inject purpose into hours otherwise spent in a restrictive environment. Each piece of art feels like a quiet statement: “I am still here, still thinking, still creating, and living in ways you might not expect.”

Their art is in stark contrast to the limitations of the system. Prisons are increasingly strained by understaffing, leading to lockdowns and limited programming. But art is something people in prison can do on their own. So artistic expression can still flourish in a system that limits access to meaningful programming, education or job training.

One man incarcerated in Kansas, working on his newfound drawing hobby, sent us an image of what he sees outside his window.

Another man, incarcerated in New York, recreated the cover of his current favorite book, “Principles of Kingdom Transformation” by Stanley R. Saunders.

Another person, incarcerated in Louisiana, sent in a poem about the casual violence he often witnesses while eating breakfast. He shared that his brother, the only person who had read the poems, “doesn’t like them, but he does detect the emotion in them.”

Celebrity advocacy for criminal justice reform reveals where policies and institutions have failed.

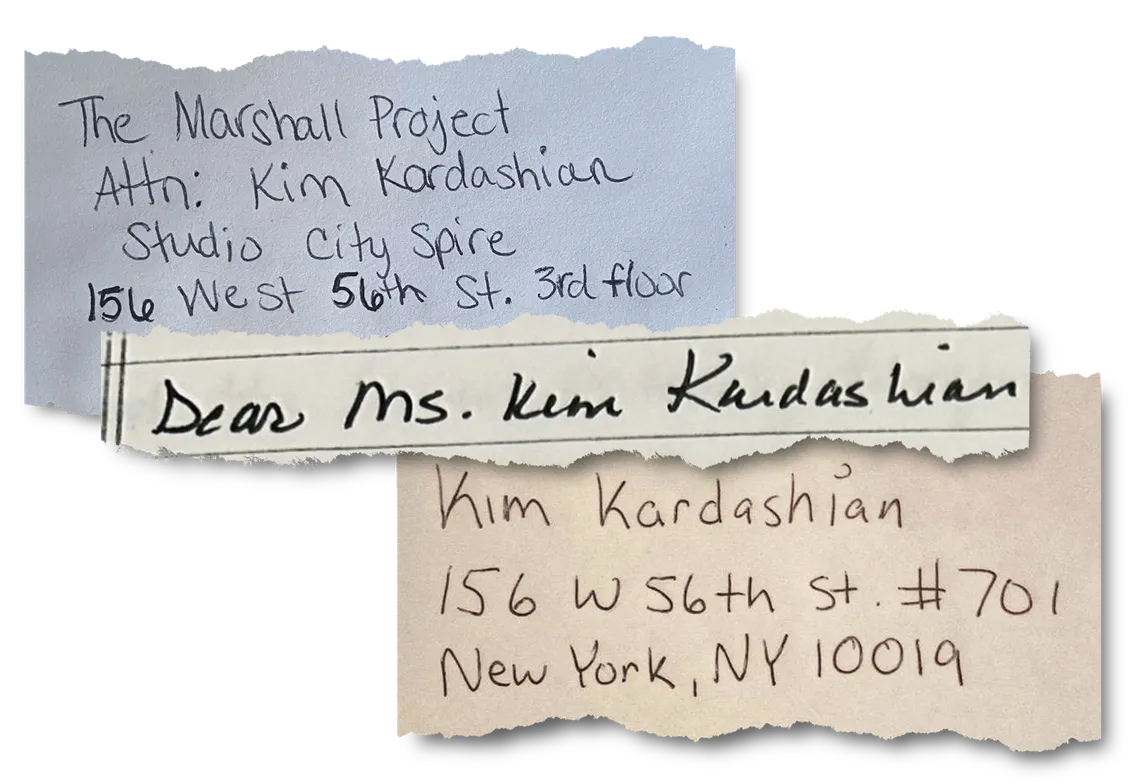

The Marshall Project receives scores of letters addressed “To the Offices of Kim K.”

Kim Kardashian has become one of the most recognizable faces of prisoner advocacy in recent years. She helped secure freedom for Alice Marie Johnson, a grandmother serving life for a nonviolent drug offense. Since then, she’s used her popular television show to explore prison issues in California and even attended a criminal justice reform roundtable at the White House.

Each letter to Kardashian highlights the systemic issues that make it necessary for celebrities to step in where policies and institutions fail. For years, criminal justice advocates have lobbied sitting presidents to help clear the Department of Justice’s lengthy clemency backlog. President Joe Biden inherited over 14,000 petitions for clemency from the previous administrations. He pardoned his son Hunter Biden in December, but has made nearly no progress addressing the list. In recent years, presidents have used their pardoning power less and less frequently while their limited decisions have become increasingly political.

If you’re curious, I did go down the rabbit hole of trying to figure out why people think we work with Kardashian. It turns out that one of our staff members was interviewed for “Kim Kardashian West: The Justice Project.” And The Marshall Project is the only newsroom in the U.S. to publish a magazine specifically for incarcerated people, which is how many people in prison come across our work (learn more about News Inside here).

Prisons fuel loneliness, yet are excluded from the public health conversation.

Last year, the U.S. Surgeon General Vivek Murthy declared loneliness an “epidemic,” comparing its negative effects to smoking up to 15 cigarettes a day. The advisory makes clear that emotional connection — or the lack of it — seriously affects individual and societal health. But his vision didn’t include prisons and jails, home to nearly 2 million people.

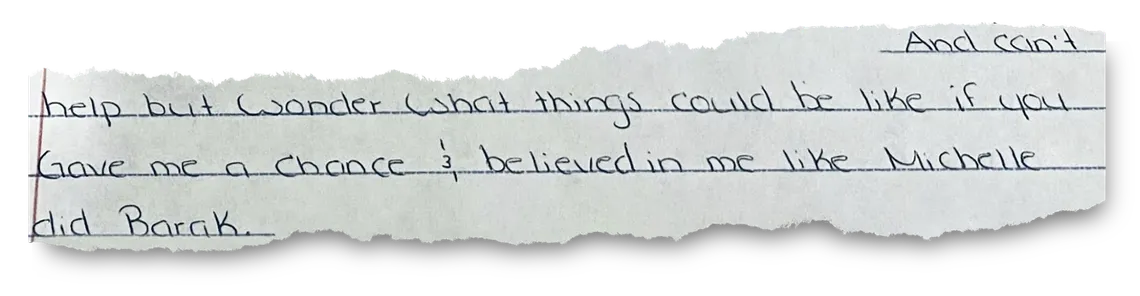

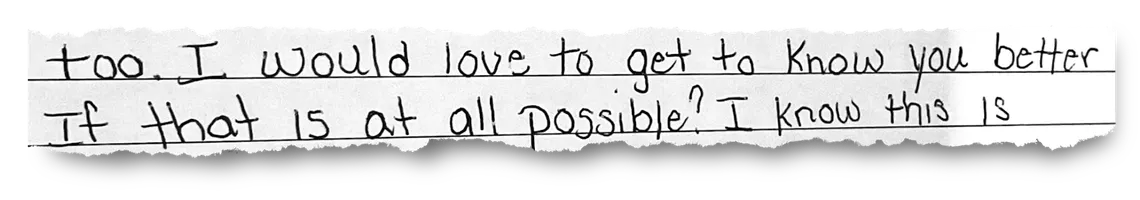

We see this loneliness epidemic reflected in the mail in a number of ways. We receive quite a few letters addressed to our female reporters — some direct, like, “I want to get to know you better,” and others more subtle, like, “Can we talk?” Some writers are bashful about their request (“Pardon my intrusion”), while others use their lengthy sentence as an excuse (“... due to 30 years of sexual deprivation”). The need for connection is also reflected in the many letters asking for advice on finding pen pals or building meaningful relationships, both inside and outside of prison.

Prisons and jails don’t just isolate; they engineer disconnection. From the barriers to visiting loved ones, to the stigma that discourages communication with the outside world, incarceration entrenches loneliness in ways few other environments do.

Small, everyday complaints show how prison slowly erodes dignity.

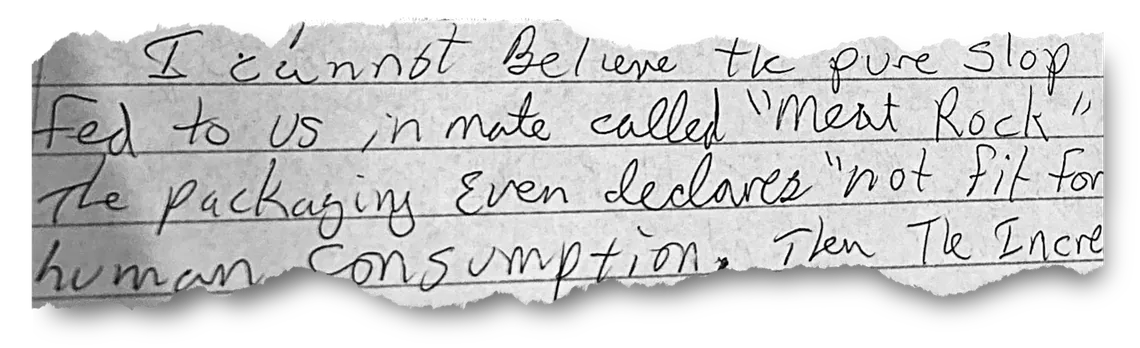

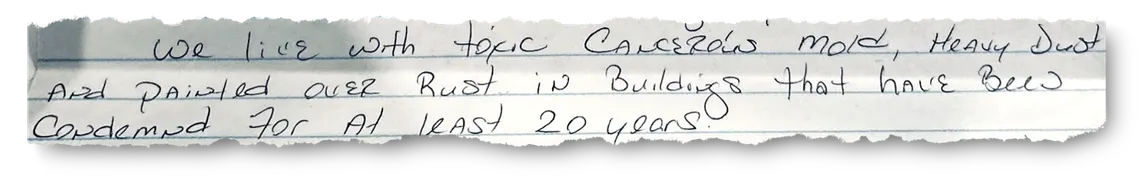

The small details that people share in their letters are often the ones that stand out the most. These seemingly trivial details reveal the harshness and neglect of daily life inside.

One man incarcerated in Virginia wrote to us recently about the food: “pure slop” he calls it, including meat labeled “not fit for human consumption” and “yeastless” bread that crumbles if you touch it. Another man, in Illinois, noticed the heavy layer of dust that settles everywhere. He pointed out rusted walls, painted over instead of being replaced, in a building he says has been “condemned for at least 20 years.” Another man wrote to us about how expensive commissary hygiene products are. In his facility in Ohio, a 4-ounce bottle of shampoo can cost up to $2. He lamented that it’s so pricey, staying clean feels impossible unless you’re willing to go broke.

These aren’t stories of outright abuse and violence — though we do get many of those, too. One man incarcerated in New York described the “air of fear” that comes when officers stop wearing name tags. Without a name, he says, there’s no way to hold anyone accountable if they mistreat you.

These everyday things — the food, the dust, the noise, the lack of hygiene — wear people down over time.

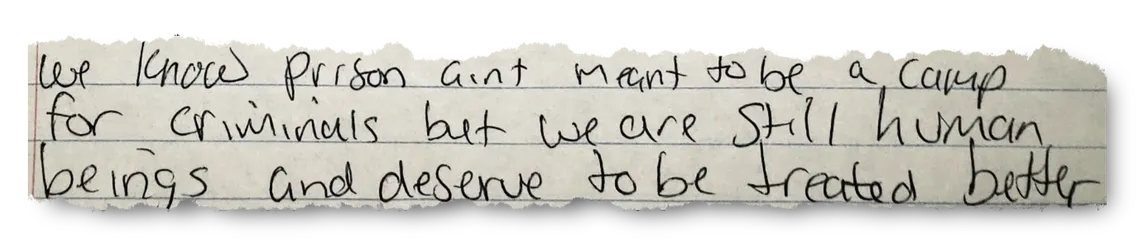

“We know prison ain’t meant to be a camp for criminals,” one man wrote. “But we are still human beings and deserve to be treated better.”