This is The Marshall Project’s Closing Argument newsletter, a weekly deep dive into a key criminal justice issue. Want this delivered to your inbox? Subscribe to future newsletters.

At a campaign rally in the border state of Arizona on Thursday, Donald Trump roused the crowd with a promise to undertake the largest mass deportation in U.S. history, after lamenting that the country has become “like a garbage can for the world.”

This promise to round up and ship off the estimated 11 million immigrants in the U.S. who lack permanent legal status is one of Trump’s signature campaign promises in 2024, and one of his biggest applause lines. Trump has privately worried that stump speeches focused on less divisive topics — say the economy — leave his audiences bored, the New York Times reported this week.

Several recent media analyses have found that a second Trump administration would face myriad challenges in affecting mass deportation at this scale, and that the effort would require a Herculean reworking of every aspect of the criminal justice and immigration detention systems.

A study by the American Immigration Council, a pro-immigration advocacy group, calculated that the deportation effort would require hundreds of new detention facilities, and hundreds of thousands of new immigration agents, judges and other staff. Fiscal analyses have concluded that mass deportation on this scale could cost hundreds of billions of dollars. Even at its current rate of enforcement, detention and deportation, Immigration and Customs Enforcement is already hindered in its “ability to maintain a safe and secure environment for staff and detainees,” at its facilities according to a Department of Homeland Security watchdog report released last month. Many of those detention locations are run by private companies on former prison grounds. Bloomberg News reports this week that Trump’s deportation plan could mean a huge financial opportunity for operators like CoreCivic and GEO Group.

To get around the already backlogged deportation system, Trump and his advisors have said they intend to invoke the Alien Enemies Act of 1798. The law — which was used during the two World Wars — allows the president to arrest, imprison or deport immigrants from a country considered an enemy of the U.S. during wartime without the usual due process. Its use would draw immediate legal challenges, and legal experts are divided over how such an effort would fare in the courts. The U.S. is not at war with any of the countries from which large numbers of migrants arrive, which the language of the act requires. Courts, however, are often deferential to the executive branch over this kind of authority.

Enforcement efforts would likely include the use of novel surveillance technology. Some tech observers worry about an increase of technology that’s already becoming ubiquitous on the border, including surveillance towers, high-tech blimps, incognito license plate readers and biometric readers.

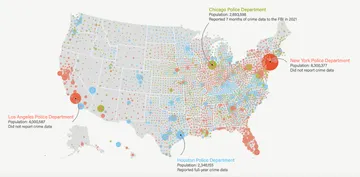

Trump has also repeatedly said he plans to mobilize local law enforcement to carry out elements of his deportation agenda, as well as the National Guard in states where the governor is sympathetic to this goal.

Some law enforcement leaders have already declared that they will not participate in mass deportation efforts. Even officials who have raised concerns about the challenges created by large influxes of migrants are not necessarily interested in mass deportation. In Whitewater, Wisconsin, Police Chief Dan Meyer told ProPublica that he’s been irritated by efforts to politicize the situation in his town, where at least 1,000 mostly Nicaraguan migrants have recently settled.

Meyer said his department has dealt with “very real challenges tied to the arrival of so many people from another country,” mostly related to poverty, language barriers and administrative challenges — like the fact that many migrants don’t have, and struggle to get, driver's licenses.

But what Meyer said was not happening was a migrant crime spree, a claim that’s been a cornerstone of Trump’s campaign for mass deportation. Meyer told ProPublica that the new immigrants aren’t committing crimes at a greater rate than other Whitewater residents.

In Aurora, Colorado, another police chief says that Trump’s claims don’t represent the reality on the ground. Chief Todd Chamberlain told NBC News earlier this month that the city is very safe, despite Trump describing it as “overrun” by members of the Venezuelan gang Tren De Aragua (TDA). Trump has identified Aurora as the epicenter of his deportation efforts.

Chamberlain said that there is crime related to TDA members, but that Trump’s rhetoric has dramatically overstated the situation. This week, NBC News reported that the Department of Homeland Security has identified about 600 migrants across the entire U.S. who may have connections to TDA, although some experts the outlet cited said that number was certainly an undercount.

Beyond the legal and logistical challenges of Trump’s deportation plan are profound potential economic costs. “It would certainly cause disruption and angst,” one Arkansas business leader told the New York Times, referring to the labor that migrants provide in fields that are either unattractive to U.S. workers or where there are acute shortages of homegrown labor. Some analyses suggest that a complete mass deportation could cut more than a trillion dollars of production from the U.S. economy and cause a contraction on par with the 2009 Great Recession.

None of that accounts for the human toll of mass deportations. Writing for Texas Monthly, Jack Herrera tells the story of Marco, a Honduran man in Georgia working in construction and landscaping. Marco was deported once before, in 2010, and had planned to make peace with life in Honduras. But the threat of violence by local gangs there, and the prospect of making 10 times his annual income, drew him back to the U.S. in 2021.

Like most undocumented people in the U.S., Marco lives in a mixed-status home, meaning “some relatives have citizenship or green cards and some have neither.” If Marco were deported, Herrera writes: “His family are the ones who would truly miss him — the girls waiting for their uncle to get home each sundown, with mud on his boots and wood chips on his shirt.”