The Black Shield formed in Cleveland nearly 80 years ago. Initially, Black officers came together to support and protect each other from discrimination and retaliation in the mostly White police department. In the 1970s, the association took that battle to court, fighting for a more fair system of hiring and promoting Black officers and pushing for a police force that reflected the makeup of the city.

The Black Shield has also had outspoken leaders who called out civil rights violations or police brutality. One of those leaders was Vincent Montague, who in 2020 decried racism and police brutality at protests, on panels and in the press. But Montague also had his contradictions, and a history that included shooting a Black man at a traffic stop. Read the story of Montague's rise and fall, told by Marshall Project reporter Wilbert L. Cooper.

Cooper’s forthcoming book, “The Black Shield,” will explore what it means to be a Black cop in America, through the lens of the history of one of the country’s oldest Black policing organizations and his family’s own history as Black police officers in Cleveland.

Below is a timeline of some key events in the history of the Black Shield.

1866

A year after the abolition of slavery, according to the Case Western Reserve University Encyclopedia of Cleveland History, Cleveland creates its own modern police department. There are an estimated 1,300 Black residents living in the city of about 95,000 people by 1870, according to Case Western Reserve history Professor John Grabowski. But there are no Black members of the city’s police force in its early years.

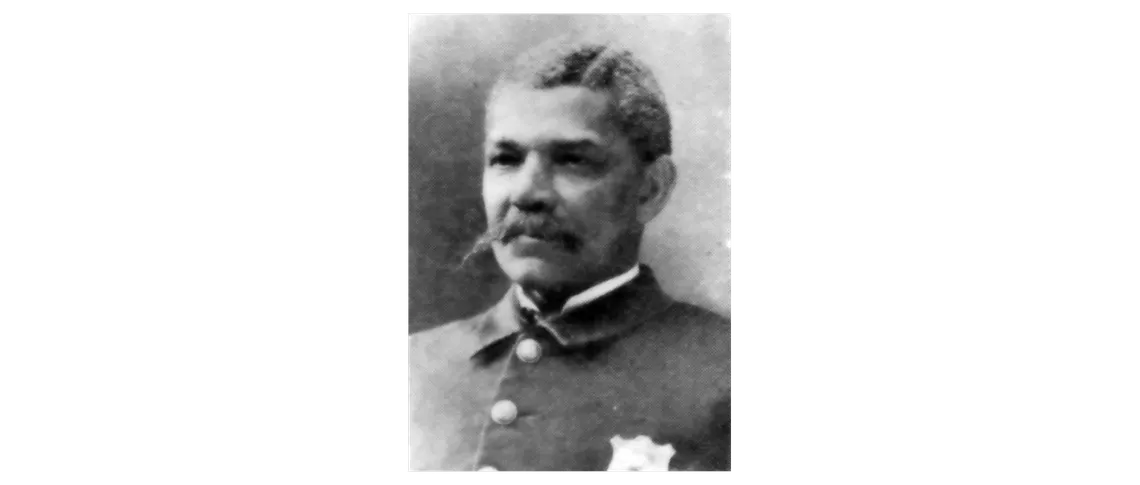

1881

According to the Cleveland Police Museum, William Manuel Tucker, a formerly enslaved man, becomes the first Black person appointed to the Cleveland police force. He’s one of the tens of thousands of Black people who migrated to the city after the Civil War.

1925

Social workers and women’s groups successfully lead a campaign to create a segregated Women’s Bureau for the police department, operated by policewomen and focused on diversion and working cases that involve women or children as victims or suspects. The bureau’s first director, trained social worker Dorothy Doan Henry, tells The Plain Dealer that they are seeking women of color to be officers because they “understand the colored problem better.”

1930

According to historian Kenneth L. Kusmer’s “A Ghetto Takes Shape: Black Cleveland, 1870-1930,” Cleveland goes from being the nation’s 15th largest city to becoming the sixth, with more than 900,000 people in 1930. During this time, the number of Black residents in the city balloons to 72,000.

1935

Cleveland officers form a chapter of the Fraternal Order of Police. Even though the union violates the department’s rules against officers organizing, the chief does not stop the efforts, according to the Encyclopedia of Cleveland History.

1945

The Fraternal Order of Police’s ranks encompass nearly half of the Cleveland police department, according to the Encyclopedia of Cleveland History. Amid this growth, Black officers who are sidelined by fraternal organizations begin to meet on their own to discuss their “unfair treatment,” according to the Black Shield Police Association’s website.

1946

According to W. Marvin Dulaney’s book, “Black Police in America,” Black Cleveland cops are galvanized by what was known as the “Euclid Beach Park Riot,” in which Black patrolman Lynn Coleman was wounded during a scuffle with private police while trying to protect Civil Rights activists at the segregated amusement park. Black officers move to create a formal organization called the Shield Club. But the city refuses to recognize the organization or its grievances, and the leaders of the group face harassment for its formation.

1950s

Faced with institutional opposition, the Shield Club becomes a social club, focusing on community service and youth athletics, according to interviews with former Shield Club President Alfred Zellner and former Shield Club Secretary Curtis Scott.

1964

Inspired by the Civil Rights Movement and the organizational efforts of other Black cops across the country, a new generation of Black officers in Cleveland begins to meet to discuss how they can pool their power to get promotions and police their community differently, according to Scott.

1968

A firefight between the Cleveland police and a Black nationalist group breaks out in Glenville, leaving several cops and citizens dead. Fearing violent retaliation from police against the Black community, the following night, the city’s first Black mayor, Carl Stokes, makes use of an all-Black squad of officers (including several future Shield Club leaders) to successfully quell unrest in the neighborhood with no casualties, according to Stokes’ memoir “Promises of Power: A Political Autobiography.”

1969

The group of Black officers that began meeting in 1964 officially calls itself the Shield Club to honor the Black officers of the past, according to former Shield Club Secretary Scott. The group is chartered as a nonprofit organization, according to Shield Club documents. Scott and former club President Zellner say its original focus is on promotions, social events and community service.

The same year, rank-and-file officers break away from the Fraternal Order of Police and launch the Cleveland Police Patrolmen’s Association to address their labor concerns. In the wake of the violence in Glenville, they also demand armored vehicles and grenade launchers, according to Stokes’ memoir. According to a 1969 Plain Dealer interview with a White police officer, officers who didn’t sign up for the CPPA were accused of being “[n-word] lovers.”

1972

Shield Club President Fred Johnson and Secretary Jean Clayton lead legal efforts to increase diversity in the police department, according to numerous internal Shield Club documents. Clayton files a lawsuit over gender discrimination at a time when police women’s careers are stymied in the segregated Women’s Bureau with unequal pay and little hope of promotion. Johnson spearheads the filing of a suit claiming that the city’s hiring and promotional practices are racially discriminatory — Cleveland’s population is 38% Black, while the police department is only 8% Black, according to court documents.

1973

Clayton’s lawsuit causes the city to disband the Women’s Bureau and integrate women into the police department, according to her obituary in The Plain Dealer.

1977

After years of litigation, the city drops its appeal of the Shield Club lawsuit and enters into a federal consent decree, agreeing to continue to follow minority hiring and promotional quotas until minority representation surpasses 35.8%, according to court documents.

1978

The Shield Club changes its name to the Black Shield Police Association, according to internal Shield Club documents.

1985

The Fraternal Order of Police successfully appeals parts of the Shield Club consent decree that apply to officer promotions, dismissing those quotas. But the hiring quotas remain in place, amended to now set the goal of minority representation in the department at 33%, according to court documents.

1995

The consent decree’s hiring quotas expire when minority representation in the department surpasses the 33% benchmark, according to court documents. However, since the start of the lawsuit, the city is even more diverse. More than half of the city’s population is Black, Hispanic or Asian, according to a Plain Dealer article.

1997

Two years after the expiration of the hiring consent decree, the number of Black cadets in police academy classes in Cleveland drops from 43% to less than 15%, according to a Plain Dealer article.

1999

Cleveland Mayor Michael R. White holds a news conference and announces an investigation into reports of bigoted graffiti in police locker rooms and racist symbolism worn by White officers. Black Shield Police Association President Anthony Ruffin supports the claims. A city investigation doesn’t find evidence of organized racism among officers, though many Black officers declined to participate citing safety concerns, according to a Plain Dealer article.

2014

A group of White officers involved in the notorious 2012 chase and fatal shooting of Timothy Russell and Malissa Williams sue the City of Cleveland for reverse racism. In their suit, they allege the department has a “history of treating non-African American officers involved in the shootings of African Americans substantially harsher than African American officers.” The lawsuit is dismissed the following year.

2016

Black Shield leadership calls on the Cleveland Police Patrolmen’s Association to retract its presidential endorsement of Donald Trump. It was the first time in the union’s history it endorsed a presidential candidate. The union doesn’t retract the endorsement, but CPPA declines to endorse a presidential candidate in 2020.

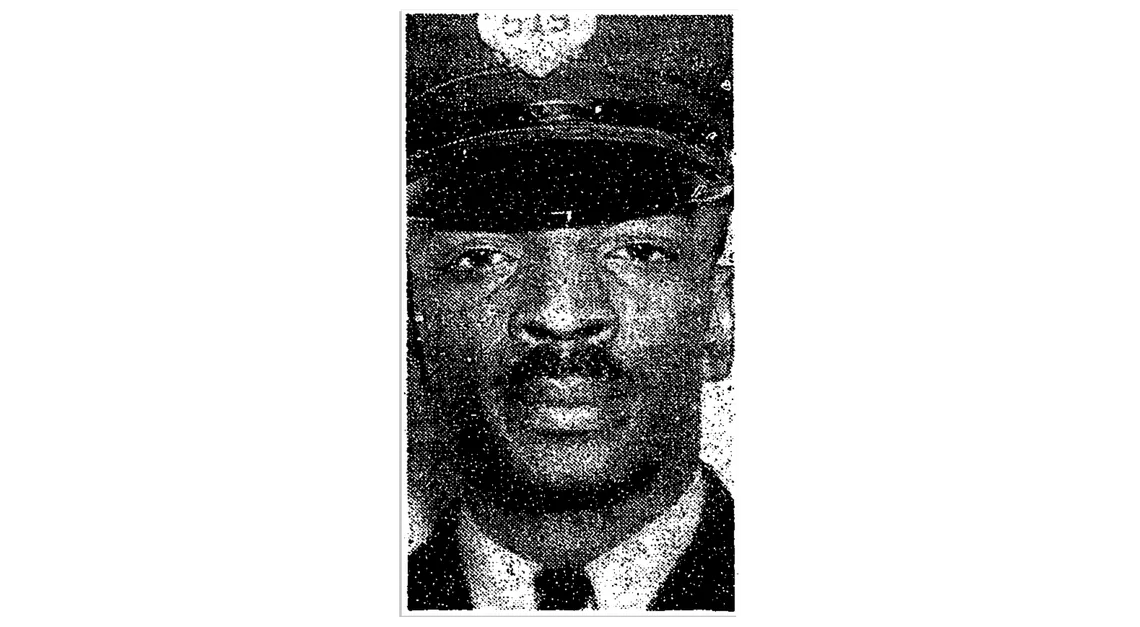

2018

Vincent Montague becomes Black Shield president and issues condolences to the family of 12-year-old Tamir Rice, who was killed by a Cleveland police officer in 2014. Tamir’s mother, Samaria, was pushing back on police union efforts to have the officer who killed her son rehired. The Black Shield offers its support and vows to aid in the family’s healing process.

2020

After the police killing of George Floyd, in a public forum, President Montague expresses the need for something “extreme, something radical,” to ensure that another person doesn’t die “unjustly by the hands of the police.” The comments generate heated responses from other officers.

2021

Montague is fired. According to the city, he was terminated because of involvement in a bribery scheme. (Montague did not face criminal charges in the case.) Montague claims he was fired in retaliation for speaking out against racism and police misconduct.

2023

The Cleveland Division of Police is nearly two-thirds White, while Cleveland’s population of people of color grows to about 47% Black and 12% Latino. The city, like many across the country, struggles to recruit officers and launches a marketing campaign to attract more diverse recruits.

2024

Under the leadership of current President Mister Jackson, the Black Shield is focusing less on the issues of the Black community and more on internal issues faced by Black officers. “Vince made a lot of dynamic moves,” Jackson told The Marshall Project. “After that, not only myself, but our members have become a lot more cautious.”

An earlier version of this story incorrectly stated the timing of Vincent Montague’s termination from employment with the Cleveland police department.