A vast web of institutions that detain immigrants stretches through every major city in the United States. And while undocumented people often power the restaurants and construct the skyscrapers in these urban centers, the detention centers and county jails where they’ve been held for months, or even years, are often invisible to people on the outside.

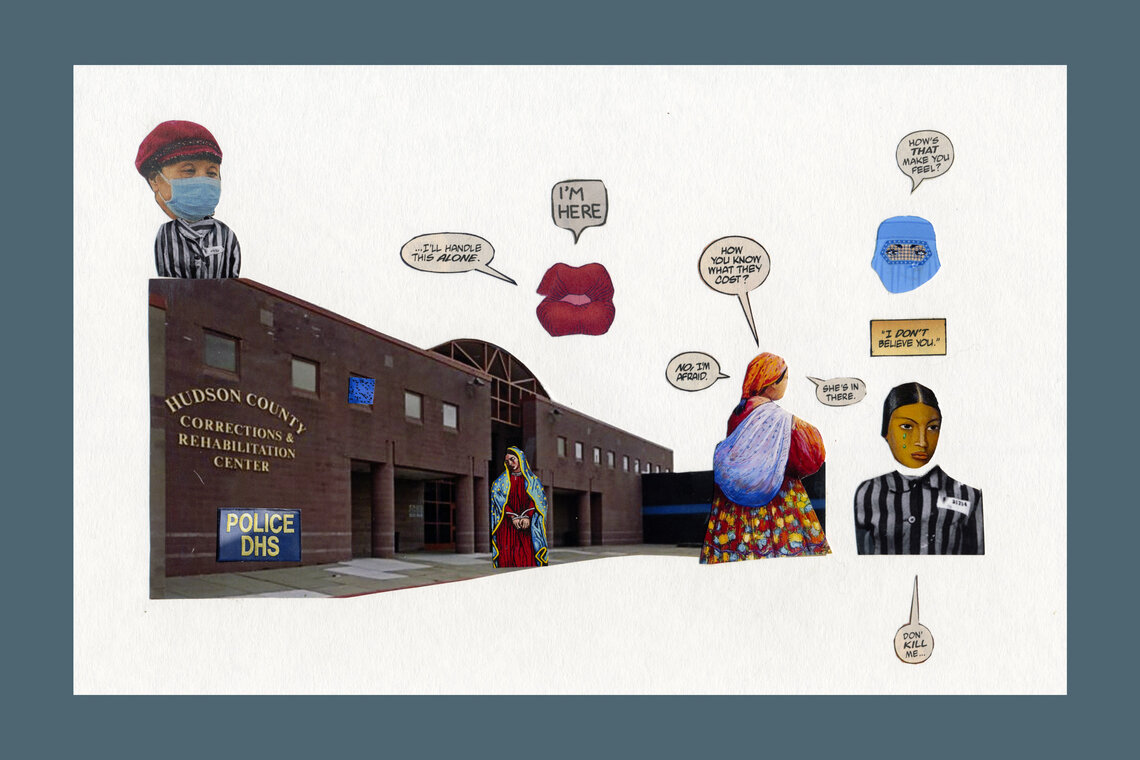

In her multimedia project “Spaces of Detention,” photographer and anthropologist Cinthya Santos-Briones pairs the drawings, poetry and oral histories of formerly detained immigrants with collages she makes to shine a light on life in four New Jersey facilities: the Elizabeth Detention Center and the Bergen, Essex and Hudson County jails.

Through contracts with Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE), the jails currently hold 117 undocumented people, according to the most recent available count by ICE officials. The number is much lower than in previous years. Elizabeth Detention Center, a for-profit facility run by CoreCivic, currently holds about 138 migrants.

All four lockups have faced years of lawsuits, protests, an unprecedented wave of hunger strikes decrying inadequate medical care, lack of due process for detainees and a failure to protect the people they incarcerate from COVID-19. Essex County ended its engagement with ICE in May, claiming that it made a more lucrative deal to incarcerate people from neighboring Union County Jail, which is closing.

In late June, the New Jersey state legislature passed a bill that would bar county jails from contracting with ICE and prohibit the state from entering into agreements with private immigration detention facilities. If Gov. Phil Murphy signs the bill, New Jersey will become the fifth state in the nation to stop counties from signing new contracts with federal immigration authorities.

Briones began curating “Spaces of Detention” during the Trump years. As the former president’s anti-immigrant rhetoric and policies intensified news coverage of the U.S.-Mexico border, Briones, who is Mexican, became tired of the barrage of traumatic images of crossings.

“I got to a point where I didn’t want to see any more pictures of parents being separated from their children and cells full of immigrants who were cold and hungry,” says Briones, who lives in New York City and self identifies as a “migrant artist of color with Indigenous and mestizas roots.”

“There is a lucrative market for photos that show the pain of ‘the other.’ I was very tired of seeing images like this while almost nothing was changing.”

Rather than focus on what Trump characterized as a “border crisis,” Briones says she wanted to create a space for migrants to tell their own stories. To gather material, she met with small groups of formerly detained people at Brooklyn’s Lutheran Church of the Good Shepherd, which serves as a hub for undocumented people. Briones volunteers at Good Shepherd alongside her husband, Pastor Juan Carlos Ruiz. The artist also held one-on-one workshops at the homes of some participants.

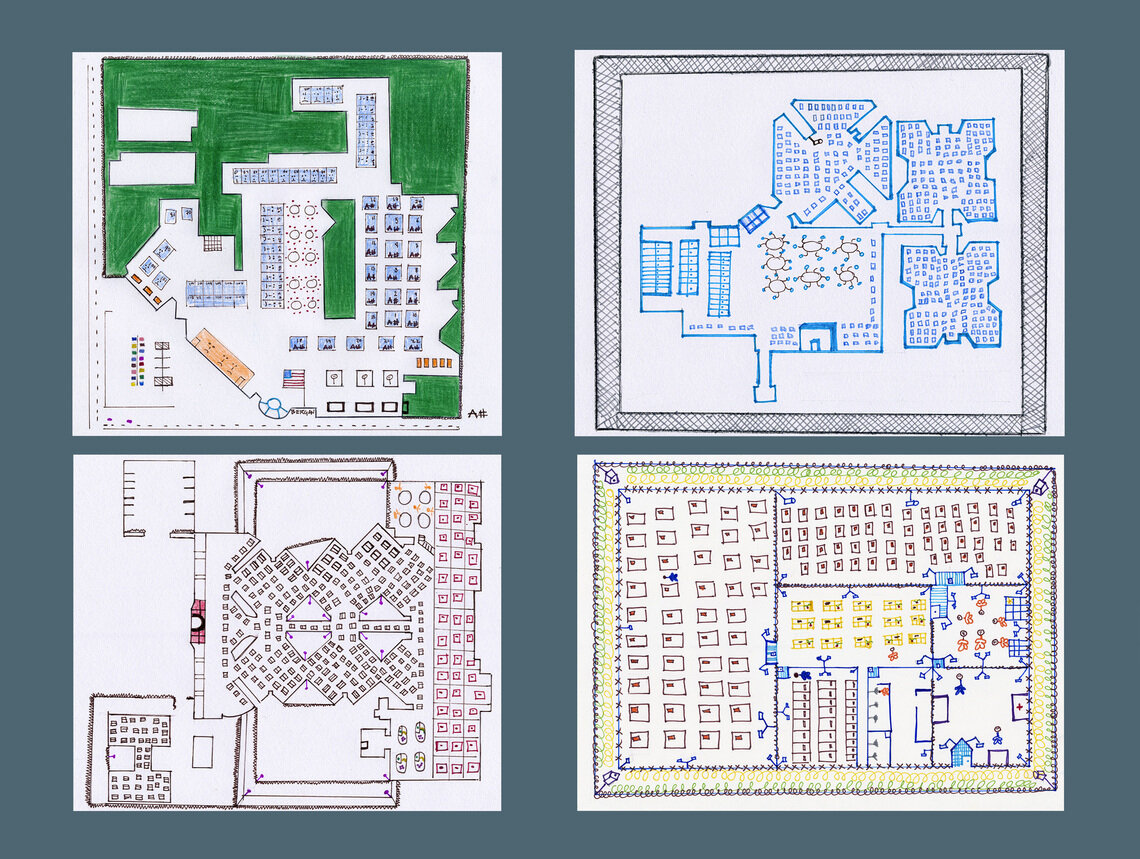

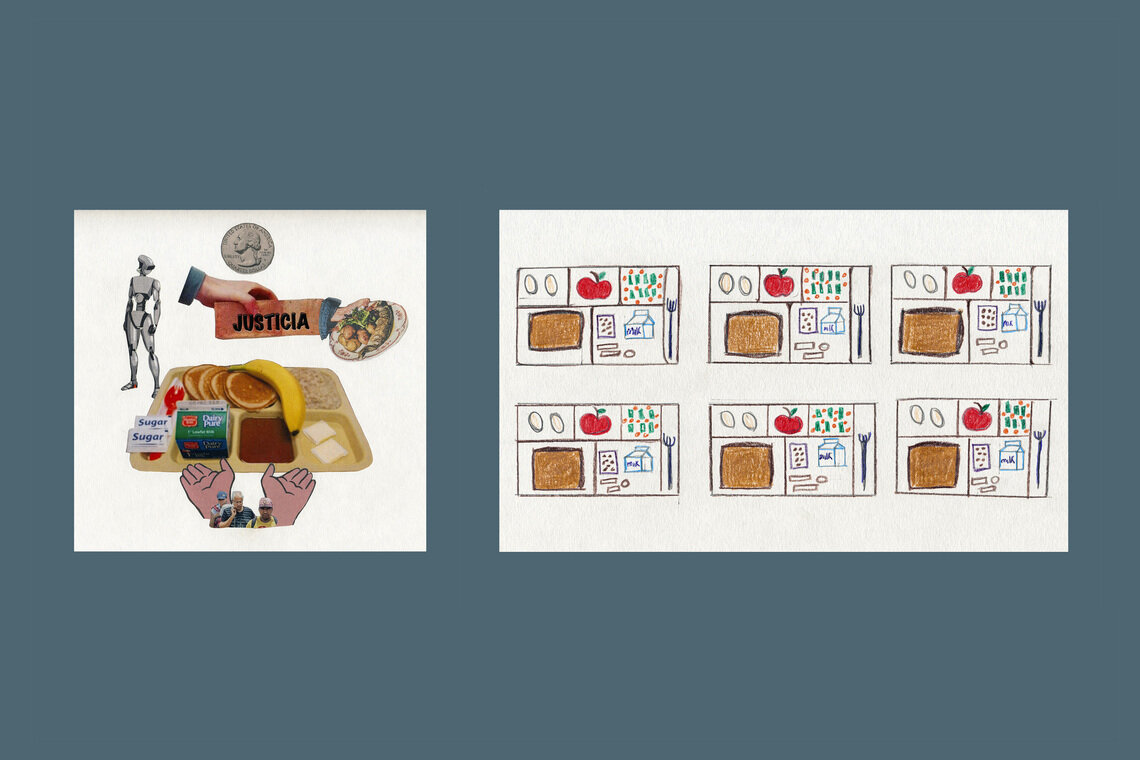

Briones invited workshop attendees to draw the physical spaces where they were held and narrate features of their confinement. The results were detailed images of brick walls, prison layouts, security cameras, metal fences and tray after tray of processed food. The overall theme is the drowning monotony of life behind bars.

Briones’ collages combine images from the media with her own photographs to represent subjects’ homelands, their multi-national routes to the U.S., and the political and economic displacement often at the root of their migration. She had originally planned to collaborate on the collages with workshop attendees, but COVID-19 made sharing materials risky.

So far, about 17 people have participated in the project. Most workshop-goers are from Honduras, Guatemala, El Salvador, Venezuela and Mexico. Of that group, many are Indigenous, from the Ki’che’, Mam and Mixteco communities of Guatemala and Mexico. One participant is from Zimbabwe.

Isaac Garay Ponce, a Salvadoran immigrant who cleans offices in Jersey City, participated in a workshop last year. He lives five minutes away from the Hudson County Jail where he was detained for three years before winning his asylum case in 2019.

“I pass by there all the time, and I remember those times with mixed feelings,” said the 31-year-old who crossed into the U.S. in 2015 after receiving death threats from gangs in El Salvador. “No one else can talk about what happens on the inside like we can. No one is going to tell you that the food is bad. That you have to cry in order for someone to give you a roll of toilet paper. That the showers are so hot that they burn your skin. That the officers are racist. So it's better for people who have been inside to give others an idea of what it's like.”

Ponce, like many workshop participants, highlighted how the county jails rely on different uniforms and physical spaces to delineate immigrant detainees from incarcerated citizens.

“People call you a ‘detainee’ or a ‘prisoner,’ but there is no difference for me,” he says. “You bathe at the same time; you have rec at the same time; you eat at the same time. What you really come to understand is that you are no longer Isaac or Juan or Ernesto. You are a number.”

Briones hopes that by creating community spaces for storytelling, the project can go beyond participants’ trauma. For Ponce, survival in detention required envisioning a future on the outside. Inside, he learned English by talking to other detainees, and he used his skills to read about the U.S. legal system and fight his own asylum case.

“Now, I see my life now 10 years from today,” he says. “If I could survive three years eating bad food, struggling with solitude, navigating the tempers of others, and the mistreatment of the authorities, I don't think there is anything I can’t do. You would be surprised about all of the things we could do in such a limited space.”

“Spaces of Detention” is a continuing project. It can be found on Cinthya Santos-Briones’ website and is currently featured in the We, Women exhibition at Photoville this year in New York City. The exhibit will be on public display until September 12 at the Empire Fulton Lawn.