Feature | Filed

Before her husband was deported, Seleste Hernandez was paying taxes and credit card bills. She was earning her way and liking it.

But after her husband, Pedro, was forced to return to Mexico, her family lost his income from a job at a commercial greenhouse. Seleste had to quit her nursing aide position, staying home to care for her severely disabled son. Now she is trapped, grieving for a faraway spouse and relying on public assistance just to scrape by.

She went, in her eyes, from paying taxes to depending on taxpayers. “I’m back to feeling worthless,” she says.

Across the country, hundreds of thousands of American families are coping with anguish compounded by steep financial decline after a spouse’s or parent’s deportation, a more enduring form of family separation than President Trump’s policy that took children from parents at the border.

Trump has broadened the targets of deportation to include many immigrants with no serious criminal records. While the benefits to communities from these removals are unclear, the costs—to devastated American families and to the public purse—are coming into focus. The hardships for the families have only deepened with the economic strains of the coronavirus.

A new Marshall Project analysis with the Center for Migration Studies found that just under 6.1 million American citizen children live in households with at least one undocumented family member vulnerable to deportation—and household incomes drop by nearly half after deportation.

About 331,900 American children have a parent who has legal protection under DACA, or Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals, the program that shields immigrants who came here as children. After the Supreme Court ruled on Thursday that Trump’s cancellation of the DACA program was unlawful, those families still have protection from deportation. But the court’s decision allows the president to try to cancel the program again. The debate cast light on the larger population of 10.7 million undocumented immigrants who have made lives in the country, raising pressure on Congress to open a path to permanent legal status for all of them.

We examined the impact of the wrenching losses after deportation and the potential costs to American taxpayers of expelling immigrants who are parents or spouses of citizens.

After an immigrant breadwinner is gone, many families that once were self-sufficient must rely on social welfare programs to survive. With the trauma of a banished parent, some children fail in schools or require expensive medical and mental health care. As family savings are depleted, American children struggle financially to stay in school or attend college.

Three families in northeastern Ohio, a region where Trump’s deportations have taken a heavy toll, show the high price of these expulsions.

Seleste Hernandez is now the sole caregiver for her 30-year-old son Juan, barely able to haul his 140-pound frame from his bed to his wheelchair and living with a pinched nerve in her back.

After Esperanza Pacheco was deported to Mexico from the country she had lived in for 23 years, two of her four American daughters attempted suicide, requiring emergency medical care that the uninsured family cannot pay.

Alfredo Ramos’s two American children suffered the hardest loss after he was forced to leave the United States. He was gunned down on a city street in his hometown in Mexico.

These families are part of a large and growing group of American households hit by deportation. From 2013 to 2018, more than 231,000 immigrants who were deported said they had American citizen children, according to the most recent data available from Immigration and Customs Enforcement, or ICE.

The number of children whose family members could face deportation is much larger. The figure of just under 6.1 million U.S. citizen children living in what are called mixed-status families with undocumented members was derived from a new analysis of 2018 Census data for The Marshall Project by the Center for Migration Studies, a research organization in New York affiliated with the Catholic Church.

When the earnings of undocumented immigrants are taken away from their households, family income plummets by as much as 45 percent, the center’s analysis found. Nationwide, about 908,891 households with at least one American child would fall below federal poverty levels if their undocumented breadwinners were removed, according to the analysis, making their American members eligible to draw public benefits, such as food assistance and, in many states, Medicaid.

When undocumented breadwinners are deported, families risk falling into poverty

Under rules established by President Trump, any undocumented immigrant in the United States can be deported. Over half of mixed-status families — with at least one undocumented immigrant and one U.S.-citizen child — fall below the poverty line, nationwide. Data show that about 909,000 more mixed-status families risk falling into poverty if their undocumented breadwinners are deported.

Another program Trump is trying to end is Temporary Protected Status, or TPS, specifically the legal status it has provided for immigrants from six countries, including El Salvador, Honduras and Haiti. About 210,600 U.S. citizen children have a parent with TPS, according to the Center for Migration Studies analysis. Trump’s plans to shut down this program for those countries remain held up in federal courts. Like the DACA program, TPS only accepts immigrants who have no serious criminal record.

Despite his tough talk, Trump’s record on deportations is mixed. Under his administration the numbers have climbed, reaching 337,287 deportations in 2018—the latest figures available—but still well below the peak of 432,281 set by President Obama in 2013, according to Department of Homeland Security statistics.

Yet under Trump, any immigrant without legal status is vulnerable, after he reversed a 2014 Obama administration directive that instructed ICE to concentrate on removing immigrants convicted of serious crimes or posing other public security threats.

In each year under Trump the number of deportees with no criminal convictions has increased, from 98,420 in 2017 to 117,117 in 2019—43 percent of all deportations last year, according to ICE reports.

Many of those recorded as criminals are immigrants whose crime was to cross the border without documents. According to the most recent data from the Bureau of Justice Statistics, 85 percent of immigrants arrested on federal charges in 2018—a total of 105,748 arrests—were accused of immigration crimes, mainly entering the country illegally. In March, due to the coronavirus, ICE said deportations of some immigrants who do not pose immediate public safety threats would be delayed. But the agency still removed 17,965 people that month.

ICE officials say their strategy is working to make communities safer because they are taking lawbreakers off the streets.

“These individuals, they’re here illegally, and they’re committing crimes,” said Matthew Albence, the senior official serving as director of ICE, at a press conference earlier this year laying out the agency’s approach. “The crime rate should be zero because the people here illegally shouldn’t be here to begin with.”

Back in 2004, when Seleste Wisniewski met Pedro Hernandez in her hometown of Elyria, she was a harried single mother from Ohio’s battered working class, raising three children, including a son with cerebral palsy.

But Hernandez was not put off. He won her heart, she said, by bringing her a ripe watermelon instead of flowers, to show her his pride in his farming skills.

He moved in and soon they had a routine. Pedro went to his landscaping job in the early morning. Seleste, a nursing assistant for the elderly, worked at night. They alternated the care of her son Juan, who doesn’t talk and can’t eat or move on his own. Together Pedro and Seleste had a son, Luis, now 11.

Pedro was never convicted of a crime. He had been deported three times but, as is general practice in immigration cases, his illegal entries were handled as civil, not criminal, violations. Like many unauthorized immigrants, Pedro was given a chance under Obama to gain legal immigration status. Under Trump, that chance was taken away.

In 2013, Pedro was stopped by local police for a broken license plate light. Instead of settling for a ticket, the police turned him over to the Border Patrol. Twelve years earlier, he had been deported after crossing the border without papers, so the Border Patrol deported him again. Determined to get back to his family, he crossed again illegally. But immigration agents were tracking him and arrested him soon after he returned home in July 2013. This time they charged him with illegal re-entry, a federal felony, hoping to send him to prison.

When Pedro was led in handcuffs into a federal courtroom in Cleveland, Juan, in a wheelchair, let out an agitated cry. The judge and the prosecutor said they were surprised to learn that Pedro was supporting a family member with a disability. They quickly agreed to dismiss the criminal case, court records show.

By then Obama was discouraging ICE from expelling immigrants with no criminal convictions. Pedro was granted a stay of deportation. For the next four years, according to his case file, he checked in regularly with ICE. He received a work permit, and with that he got a driver’s license, a full-time job growing poinsettias at a local greenhouse, even a 401K retirement account. He and Seleste got married. Her application for his permanent resident green card was approved.

In a letter to his lawyer, ICE officials said Pedro was officially off their list of priorities for deportation.

That changed under Trump. On Aug. 8, 2017, ICE agents went to the Hernandez home, ordering Pedro to leave by Sept. 30.

“You got something wrong,” Seleste insisted. “What has changed?”

There is a new president and a new administration, an agent told her.

“Sir, we’re still the same family,” she protested. “We’re doing everything we were supposed to.”

An ICE spokesman, Khaalid Walls, said the agency had acted because Pedro was a “repeat immigration violator.” On Sept. 28 he was put aboard a flight to Mexico. At the door of the plane, ICE officers handed him a notice: he was barred from returning for 20 years.

“We were getting there,” Seleste said, between hurt and rage. “We’re almost there. And then, boom, get out. And I’m left to put the pieces together.”

These days Pedro is farming a corn patch in the mountains above Acapulco, scratching out just enough to eat. Seleste is home with Juan, who requires regular feeding through a stomach tube. Someone must be near him at all times.

When both Pedro and Seleste were working, they made about $4,300 a month, enough to buy groceries, pay the bills and buy Pedro a scarlet red pickup truck. They paid taxes and had health insurance through their employers.

Now Seleste must draw on public services to survive. She had to leave her job at an elderly care center to care for Juan. The household income dropped to zero, and her housing subsidy, which she had long received as disability assistance for Juan, soared from $90 to $811 a month, with the county housing authority now paying her entire rent. She receives $509 a month in food stamps.

She lost her private health insurance and is on Medicaid. She was paid $1,200 from the federal coronavirus stimulus.

Leaders in the community took note of the family’s fall. “Pedro was a contributor,” said the Rev. Charlie Diedrick, the priest at St. Mary’s Church in Elyria, where Pedro attended Mass and Luis attends school. “He was a hard worker, took care of his family and his neighbors. And we put an end to that.”

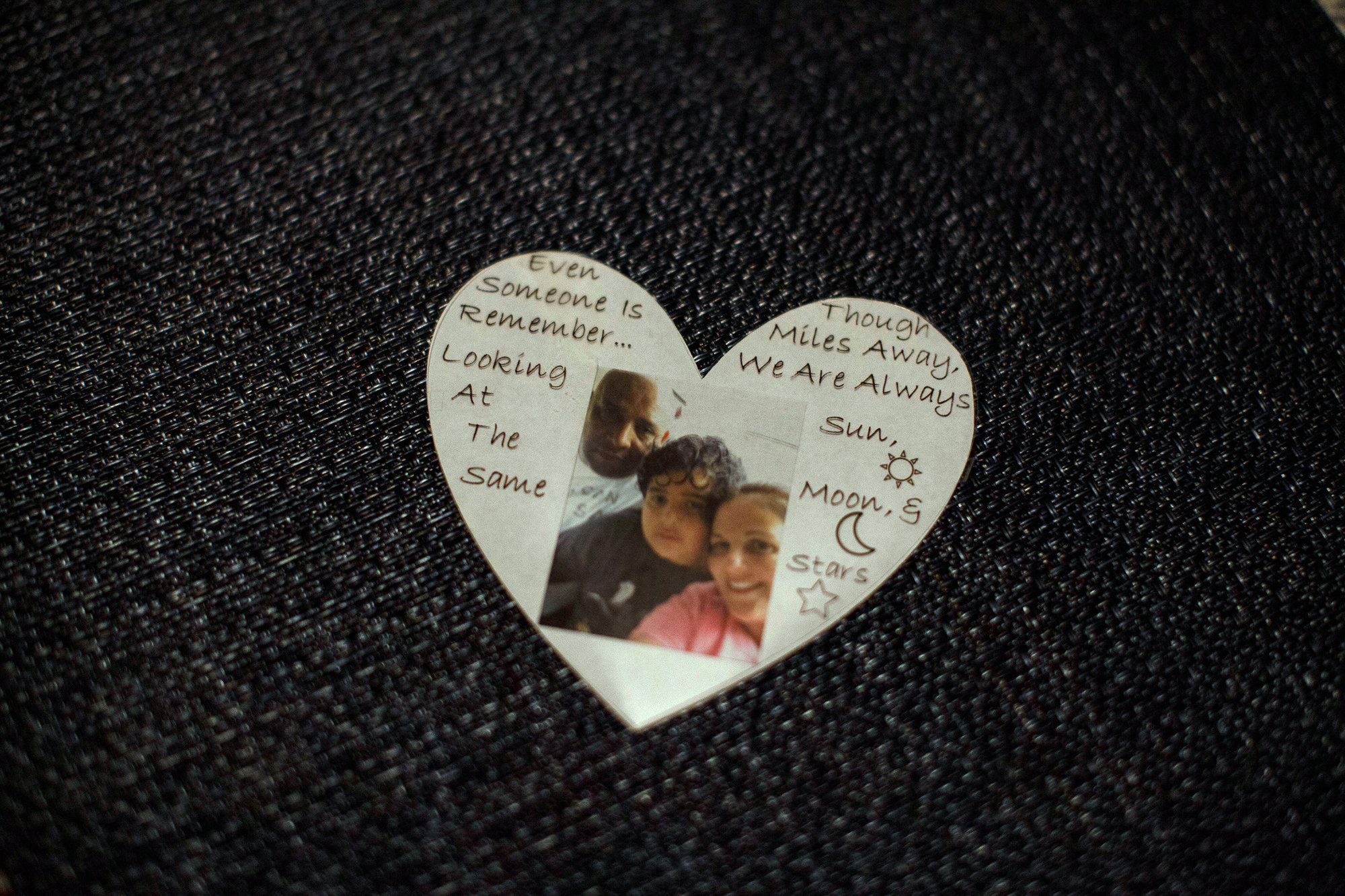

Seleste organizes her day around four or five fleeting conversations by WhatsApp, when Juan is calmed by hearing Pedro’s distant voice from Mexico. With the coronavirus threatening his frail health, Juan can never leave the house. Pandemic travel restrictions have cut Luis off from his summer visit to his father.

“Only thing I know is me, my kids, we sit in disbelief, struggling,” Seleste said. “Unnecessary suffering of the separation. Unnecessary worry. Is the country a safer place?”

In November 2017, Esperanza Pacheco went to the ICE office in Cleveland for a regular check-in. She was detained and never came out. A week later, she was dropped by ICE in Nuevo Laredo, Mexico.

“We never got to say goodbye, nothing,” said Thalia Moctezuma, her American daughter, who was 18 and a high school senior at the time. “If they are taking away a mother from a child, the child should at least get to hug her.”

The northeast Ohio town of Painesville, where Pacheco lived, has been an epicenter of enforcement under Trump. Immigrants, mainly from Mexico, were drawn to the town in the 1990s, and today 28 percent of the population is Hispanic, Census figures show. Since 2017 ICE has been tracking down undocumented people in town and cancelling stays of deportation, leading to dozens of deportations. Many undocumented immigrants, under pressure, packed up and left on their own.

“There used to be so much energy,” said Veronica Dahlberg, executive director of HOLA, an immigrant advocacy group in Painesville. “What you see now is a community that is very demoralized.”

Pacheco, a vivacious woman with an infectious giggle, is one of 14 children of a Mexican bracero farmworker who years ago became a U.S. citizen. He applied for citizenship for his children and all were approved. But due to bureaucratic errors and delays, Pacheco’s naturalization never went through.

In more than two decades living in the United States, she married another Mexican, Eusebio Moctezuma, now a legal resident, and had four daughters born in Ohio. Pacheco had one blot on her record, from a day in 2002 when she left two of the girls, just toddlers, alone in her trailer home to run to a job interview. A neighbor called the police, and Pacheco drew a misdemeanor conviction for endangering a child.

Ten years later, under Obama, ICE threatened to deport her. HOLA mobilized. Her daughters made signs and marched in Painesville streets. ICE desisted, citing Pacheco’s role as the mother of American citizens. She was granted a deportation stay and a work permit. By 2017 Pacheco’s oldest daughter was about to turn 21 and was ready to present a new petition for a green card for her mother.

Then Trump took office. Fifteen years after Pacheco’s maternal lapse, ICE officials pointed to that offense to categorize her as a convicted criminal and to justify deporting her, separating her from her daughters.

The girls were cast adrift. Their father had to work extra hours at his landscaping construction job to pay the bills and could rarely be home.

“When mom was here, she was cooking, talking, everything was right,” Eusebio said one morning in the kitchen of the family’s ramshackle trailer, his mood despondent. “I thought I was OK to handle my daughters. But now I find out they need mom over here. She’s the one that makes us a family together.”

Pacheco landed in a walk-up apartment in her old hometown of León, in the Mexican state of Guanajuato. She tries to console her husband and raise her daughters by WhatsApp, messaging them throughout the day.

For her daughters, it’s not the same. “In our house, I feel that vibe where it’s cold, it’s just dark,” Thalia said. “It feels like a place but not a home.”

Not long after Pacheco’s deportation, kids in the girls’ schools took to taunting them.

“They started saying, your mom’s illegal, you should have gone back to Mexico, you’re not really from here,” Eusebio said.

One daughter, M., who was 17, lashed out, getting into fistfights in the hallways. (The Marshall Project is not using the full names of the younger daughters because they were minors when their mother was deported.)

“She became so isolated, so angry,” Thalia said. “She would just be in her room with the lights off and she would cry and cry.”

M. began missing classes and drinking a mix of vodka and beer before school. A year after the deportation, Thalia came home one night to find M. passed out on the floor, foaming at the mouth, with a bottle of sleeping pills by her side. She called Pacheco and turned around her phone to show her mother that M. was unconscious.

“I wanted to fly to them, but I couldn’t do anything,” Pacheco said in a phone interview from León. Suppressing panic, she instructed Thalia on the video call how to keep M. alive and find a relative to rush her to a hospital.

M. spent a week in Rainbow Babies and Children’s Hospital in Cleveland. She went to a rehab center for another week.

“We asked her why she did that and she said, because she feels so lonely, she needed mom,” Eusebio said, his voice thick with sorrow. “They are so very close to mom,” he said.

After M. recovered, her outlook changed. She graduated from high school, got a job, and was dreaming of going to college, even law school.

But the youngest daughter, M.D., still struggled. In August 2019 she went to visit her mother in Mexico. The girls often felt torn when they returned from those visits, realizing they loved their mother, but they did not want to live with her in Mexico. M.D. begged her mother to come with her to the United States.

“Baby, I’ll be there soon,” Pacheco said, knowing it wasn’t true.

Not long after, M.D., who was then 15, imitated her sister and swallowed 60 pills of ephedrine. Her medical chart on Sept. 25 of last year, the day she entered Rainbow Hospital, stated that she was “currently admitted due to suicide attempt with ingestion.” It noted that she “has attempted to overdose 3 prior times in last 3 months.”

Doctors observed that M.D. had spurts of abnormally fast heartbeat, a result of the overdose. After two weeks in the hospital and an in-patient mental health center, on Oct. 9 she went back to Rainbow for four more days for a procedure to repair her heart.

Thalia found a diary M.D. had kept. She hated her life, she wrote, because her school friends had their mothers at home and were happy, and she didn’t have hers. Do we deserve this? she asked. Why us?

By March, M.D. was back in school and the family seemed to be stabilizing. But as the coronavirus was crippling the economy, their financial situation was already dire.

Eusebio, who was making $3,500 a month at his job, lost more than $7,000 when he missed work caring for his daughters in the hospital. When Pacheco was home, she brought in at least $350 a week cooking Mexican specialties to sell to trailer park neighbors. Now the family has to send Pacheco $100 a month to pay her rent. Three of the sisters are working instead of going to college, just to keep the family afloat.

Rainbow Hospital, and the private University Hospitals system it is part of, absorbed practically the entire cost of the medical care for both girls. The family was uninsured. Prodded from afar by Pacheco, Eusebio said he had attempted to sign up his younger daughters for Medicaid, for which they were eligible as citizens before they turned 19. But his application had stalled. In all, he paid out $500 for an ambulance for M.D. and $720 for her psychiatric treatment.

He received no bills for either girl’s emergency care or pediatric hospital stays, so the total cost to the system is unclear. Rainbow did send a bill for $9,800 for M.D.’s cardiac procedure, with instructions to set up a payment plan. But with Pacheco not home to maintain order, Eusebio says, the bill was lost.

Then Eusebio was out of work for a month with the pandemic lockdown. The family has not sought federal assistance, fearing it could hurt Pacheco’s green card application, her only hope of returning to her family.

On the other end of a mobile app, Pacheco fights desperation. “I’m Mexican,” she said, “but I hope God hears me, I don’t want to be here in Mexico.”

Alfredo Ramos had been living in the United States for nearly a decade when he met Susan Brown, an American from a blue collar family in Painesville. She was 20 at the time and a single mother. They had a joyful courtship of raucous parties and walks in the woods.

Brown became pregnant, and in 2000 she and Ramos married. But when she was in her ninth month, ICE raided the factory where Ramos was working and deported him. Two weeks later Brown, lonely and frantic without her husband, gave birth to their son, Cristian.

“I did what everybody would want to do in that situation,” Brown said. She sent Ramos $2,000 to pay a smuggler to help him cross the border illegally. He was back in Painesville a few weeks later.

Brown’s family rejoiced. “I knew he wouldn’t just walk away from a child being born,” said Jessica Brown, Susan’s sister. “We are a family that knows right from wrong. But we believed there would be a pathway for him to something legal.”

Because of Ramos’s deportation, the legal pathway proved hard to find. Two years later, a daughter, Diona, was born. To make ends meet, Brown worked two jobs, and Ramos took any work he could find, but his wages stayed low because of his undocumented status. Over time, tensions arose. Ramos and Brown divorced.

But he remained a hands-on provider, at times taking both children to live with him in a cramped Painesville apartment, vigilant that they got to school and athletic games.

“Maybe we weren’t hugging and stuff like that, but I would always know he was there for me,” Cristian said.

In March 2014, Ramos was a passenger in a vehicle that was pulled over for a minor traffic stop by local police. Without legal authority, the officers demanded his immigration papers. They turned him over to ICE.

A pattern was repeated: ICE tried to convict Ramos in federal court for an illegal entry crime. His children stood among protesters outside the courthouse in Erie, Pennsylvania, chanting support for their father. The federal prosecutor dismissed the case “in the interests of justice.” ICE relented, issuing a stay.

After that the children grew even closer to their father. Of his times spent with Ramos, Cristian said, “I just wanted it always to be this way.”

But shortly after Trump took office, ICE agents cancelled the stay and came looking for Ramos. After a month on the run from house to house in Painesville, he summoned his children. He would leave before ICE deported him, he said, so he would have a chance of returning legally to be with them someday.

“He never wanted to leave, never wanted to be separated from his children,” Brown said.

Beaming in on Facetime from a family homestead, also in León, Ramos invariably showed a smile. But on Sept. 4, 2018, a relative called from Mexico. Ramos had been killed, executed with 27 shots by a rampaging drug gang who mistook him for a rival trafficker. His children watched the funeral by video.

Susan Brown takes stock: if Ramos had been allowed to stay, he would have paid a share of Cristian’s graduation party, Diona’s car, their college fees. Now Brown’s small savings are depleted.

Cristian decided he could not afford college and enlisted in the Navy. Diona just graduated from high school, a track star whose final season of competition was halted by the pandemic. A scholarship she won to the University of Kentucky will partially pay her tuition, but loans will have to do the rest.

Brown just manages to pay her bills working in an aerospace parts factory, still going in every day during the pandemic even though she is at risk, since she has debilitating diabetes and was diagnosed last year with cancer.

Brown cannot identify a benefit from Ramos’s expulsion. But she has no difficulty assessing the cost: “Two children who are American citizens lost their father.”