Before prison, John Adkins, 43, didn’t care about politics. He watched the news regularly but said he mostly wanted to see reports about the ongoing gang violence in Southwest Detroit, where he lived. Now, after 23 years in a Michigan prison for murder, Adkins is an ardent Republican and supporter of Donald Trump.

He credits conservative media for his political education. In prison, Adkins began watching the news again but soon grew sick of “the demonization of straight, white, Christian men on CNN and MSNBC and just about all mainstream media,” he wrote, using the email system at Macomb Correctional Facility, where he is incarcerated. So he found himself drawn to right-wing shows such as “The O’Reilly Factor” and “Tucker Carlson Tonight.” The hosts’ positions on key issues such as abortion (against) and gay marriage (also against) won him over. But above all, Adkins says, he identifies as a conservative because he feels under attack by the left.

“I am so tired of the double-standard of the left in the country,” Adkins wrote. “Their rhetoric is what is divisive in this country, not Donald J. Trump’s!”

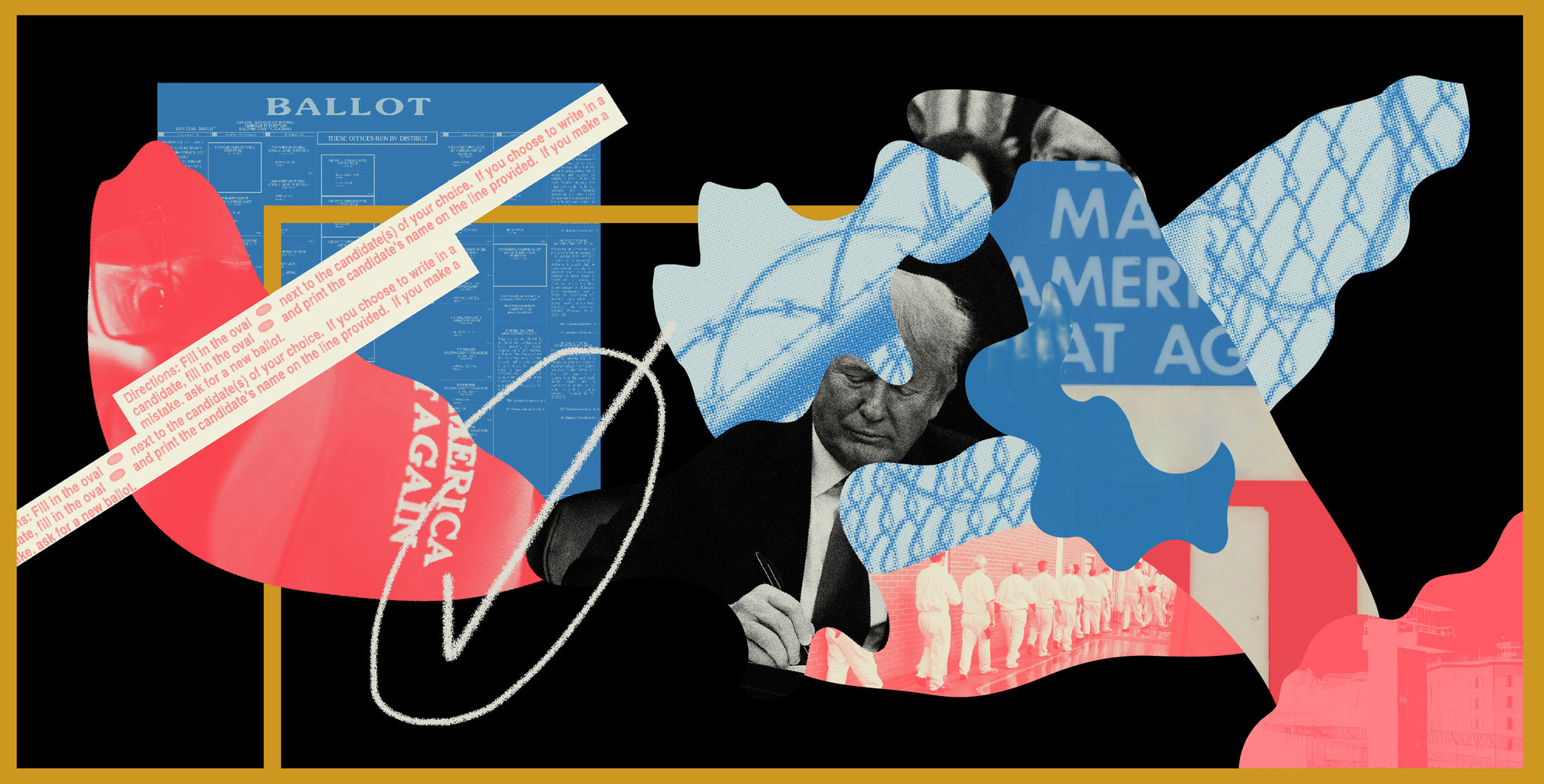

It is widely believed that the majority of people in prison are Democrats—and some Republicans who oppose restoring voting rights for released prisoners have expressed fears that they would vote Democratic. Black people, who consistently favor Democrats, are in fact overrepresented in prisons. Although white people are 64 percent of the total population, they only account for 39 percent of people in state prisons.

In a first-of-its-kind political survey of the incarcerated, The Marshall Project and Slate found that a significant share of white respondents called themselves Republicans and would vote to reelect Trump in 2020—if given the chance. Forty-five percent of white respondents backed Trump, about 30 percent picked among Democratic candidates, and the remaining 25 percent said they did not know or would not vote.

The survey is the most comprehensive snapshot of currently incarcerated people’s politics to date, but it has limitations. Respondents skewed whiter than the overall prison population, and many respondents are incarcerated in red states. As a result, it is not representative of the overall prison population. Instead of only focusing on the respondents as a whole, we looked for trends across race, gender, and other demographic differences to ensure our reported results were meaningful.

Inside prison, reasons for supporting Trump vary. Some of the reasons reflect the particular circumstances of prison life: Most prisoners share a cell, making it difficult to tune out conservative cellmates or right-wing media, or to even control which channel is on. Prisons are also notoriously segregated and can be a breeding ground for white nationalists.

Others are ideological: Some respondents are attracted to Trump’s tell-it-like-it-is personality and feel targeted by what they call political correctness on the left. And some are drawn to his policies, citing the president’s record on criminal justice and the economy.

Many survey respondents said they now spend significantly more time consuming news and following politics than they ever did before they entered prison. Some credited their political development to listening to Rush Limbaugh on a personal radio or watching Fox News on a shared television.

Christopher Shelton-Jenkins, 27, picked up his political views from a Trump-supporting cellmate. They would often discuss the news or the legal cases his cellmate had reviewed in his work at the prison law library. “I remember he talked about the Democrat and Republican stances on the wall on the border—that Democrats wanted to be all open arms, which was nice, but the Republicans thought it was just not practical in terms of managing our economy and social systems,” Shelton-Jenkins wrote in a letter. He considered his cellmate “very intelligent” and respected what he had to say. “He broke some things down to me. … That’s when I realized I had wrong and ignorant impressions.”

Before he was incarcerated, Shelton-Jenkins, who has a white mother and a black father, didn’t spend much time thinking about politics. But he felt loosely affiliated with the Democratic Party, “only because my mom labeled all Republicans racists who want to keep the rich rich and the poor poor.”

In the six years he’s been in prison in Kansas after he was convicted of murder, his understanding of politics has changed. “A lot of incarcerated, poor and black people identify as Democrat because we’re told that Republicans want to keep us poor and incarcerated,” he said. “But now I believe the opposite: that Democrats want to keep us spoon-fed by the government and Republicans want to wean us off.”

Criminal justice reform is broadly popular among Americans across the political spectrum, though Democrats are more likely than Republicans to support substantial changes to the current system. While some incarcerated Trump supporters don’t know or care what the president is doing—or not doing—on the issue, others applaud his pardoning of people convicted of nonviolent drug offenses and his signing of the bipartisan First Step Act.

The 2018 law reduces the length of some automatic federal prison sentences, gives federal judges more discretion to ignore mandatory minimum sentencing guidelines and retroactively reduces prison sentences for people convicted of federal crack cocaine offenses before 2010, among other changes. Thousands of federal prisoners have been released as a result of the law, and more could see their sentences reduced in the future.

William Robinson, a 39-year-old black man who has been incarcerated in Arkansas since 2012 for negligent homicide, points to the contrast between the punitive crime bill signed by President Bill Clinton in 1994 and the First Step Act as evidence that Trump is doing more for incarcerated people than Democrats have. Robinson also praises the Trump administration’s support for expanding the Second Chance Pell Grant program, an Obama-era initiative that allowed Robinson to earn an associate degree. He was delighted that Trump commuted the sentence of Alice Marie Johnson, who’d served two decades of a life sentence for a nonviolent drug crime.

“These things matter,” Robinson wrote in a letter. “Trump is a leader that makes hard decisions, sets trends,” while Democrats “keep playing politics.” That’s exactly the message Trump has been broadcasting as he seeks reelection. “Politicians talk about criminal justice reform. President Trump got it done,” said a campaign commercial that aired during the Super Bowl earlier this month. The ad also showed Johnson thanking Trump through tears on the day of her release.

Like many Americans, some incarcerated Trump supporters are motivated by the way he’s handled the economy. Neal Stephen, a 44-year-old white man who’s been in an Oklahoma jail for less than a year on a domestic assault and battery charge but has spent more time incarcerated on other charges, hopes the First Step Act will help the economy by saving taxpayers the cost of lengthier prison sentences. “I really can’t tell you anything that the Democrats have done in recent years, as far as criminal justice reform is concerned, that has had an impact comparable to President Trump passing these new laws,” he wrote in a letter.

Before Derek Bedford, 46, was convicted of murder, he didn’t think politics affected his life. “I was living a carefree lifestyle,” he said in a phone interview. Once he entered a Kansas prison, he started paying more attention to the news—he prefers the Wall Street Journal and Fox News—and soon became concerned that his work hours might get cut if companies that employed prisoners began sending jobs overseas.

Bedford has watched presidents come and go during his more than 20 years in prison, at times feeling disillusioned by their performance. “I was thinking that Obama was gonna do some things positive for the country, and he turned out to be a puppet for big businesses and for the rich,” he said. “I don’t see Donald Trump as being anyone’s puppet. From what I’ve been seeing and hearing, he’s given businesses some tax cuts for bringing jobs back, so that’s helping the small people in this country.”

Still, respondents’ enthusiasm for Trump doesn’t translate into optimism about the government as a whole. Four out of 5 Republican respondents say politicians rarely, sometimes or never act in their interest.

While some survey respondents call Trump a “hero” and “the best president” they’ve seen in their lifetimes, others temper their praise with caveats. Many who indicated that they’d vote to reelect Trump clarify that they don’t love everything about him, especially if their politics are more moderate. They still credit the president with trying his best to change the country for the better, even if his rhetoric is too extreme. “I would vote for President Trump again, but not because I like him. To be honest, I think he is kind of a fool,” wrote William True, a 26-year-old white man who’s been in prison in Maine for a little over four years.

True, who was convicted of murder, believes the Republican Party is less inclined to make strides on criminal justice reform but identifies with the party anyway, in part because “the Democrats demonize white males.” If some Trump policies, such as the border wall, seem a little radical to True, he still approves of their underlying principles: “If we get to the nitty gritty, he is right. Illegal immigration is a problem.”

Stephen isn’t so concerned about the brash comments and confrontational tweets that give some of his fellow incarcerated Trump supporters pause. A former member of the Army National Guard, he thinks Trump is more apt to use economic incentives and sanctions to advance U.S. interests, without projecting weakness, than to carelessly rush into war. “A strong country like the U.S. needs strong leaders that won’t back down from a fight,” he said. “I also appreciate his honesty, not being afraid to speak his mind. At least you know where you stand when you deal with a man like that.”