In 1851, the rolling green hills of Lancaster County, Pennsylvania, were the scene of the Christiana Riot, an armed uprising against the Fugitive Slave Act, which required the capture and return of enslaved people who had escaped. The revolt took place nine miles from the site of a new art installation exploring rural incarceration—a fact that was not lost on the artist, Jesse Krimes.

“It was important for me to trace the history of slavery into Jim Crow into convict leasing, into segregation and all of those things into mass incarceration,” said Krimes, a formerly-incarcerated artist whose latest work combines a series of quilts and an interactive corn maze.

The scale of the installation, called “Voices from the Heartland: Safety, Justice, and Community in Small and Rural America,” is ambitious and its components intricately detailed. But perhaps most striking is Krimes’s use of artwork and stories from incarcerated people themselves.

Born and raised in Lancaster, Pennsylvania, Jesse Krimes graduated in 2008 from nearby Millersville University with a B.A. in art. He majored in sculpture and worked in metalsmithing, helping to run the bronze foundry there. “I had taken a few basic classes on painting and printmaking,” he said, “but it wasn’t until I was incarcerated that I had to reevaluate my practice and use materials that were available to me.”

Between 2001 and 2013, Krimes served several years in state and federal prisons on cocaine-related charges. Several of his earlier pieces were created during that time.

While in solitary confinement at Dauphin County Prison in Harrisburg, Pennsylvania, he worked on “Purgatory,” a series of 300 prison-issued soap remnants imprinted with images, mostly mugshots.

“When a mugshot is in a newspaper, it’s this process of shaming, of using people as an example,” he said. “It ends up creating these very dangerous stereotypes and makes people seem like they are only this singular event.”

To create each image, he would wet the surface of the soap, place the newsprint photo on it, then dab it with wet toilet paper. When he peeled the newsprint off, an inverse image remained on the soap. To avoid detection by prison officials, Krimes would create a container out of a stack of playing cards glued together with toothpaste, hide the soap inside, and mail it to a friend.

This kind of resourcefulness is a recurring theme in Krimes’s work. For “Apokaluptein:16389067,” he stitched together 39 prison sheets and used hair gel and a plastic spoon to hand-print them with images from The New York Times.

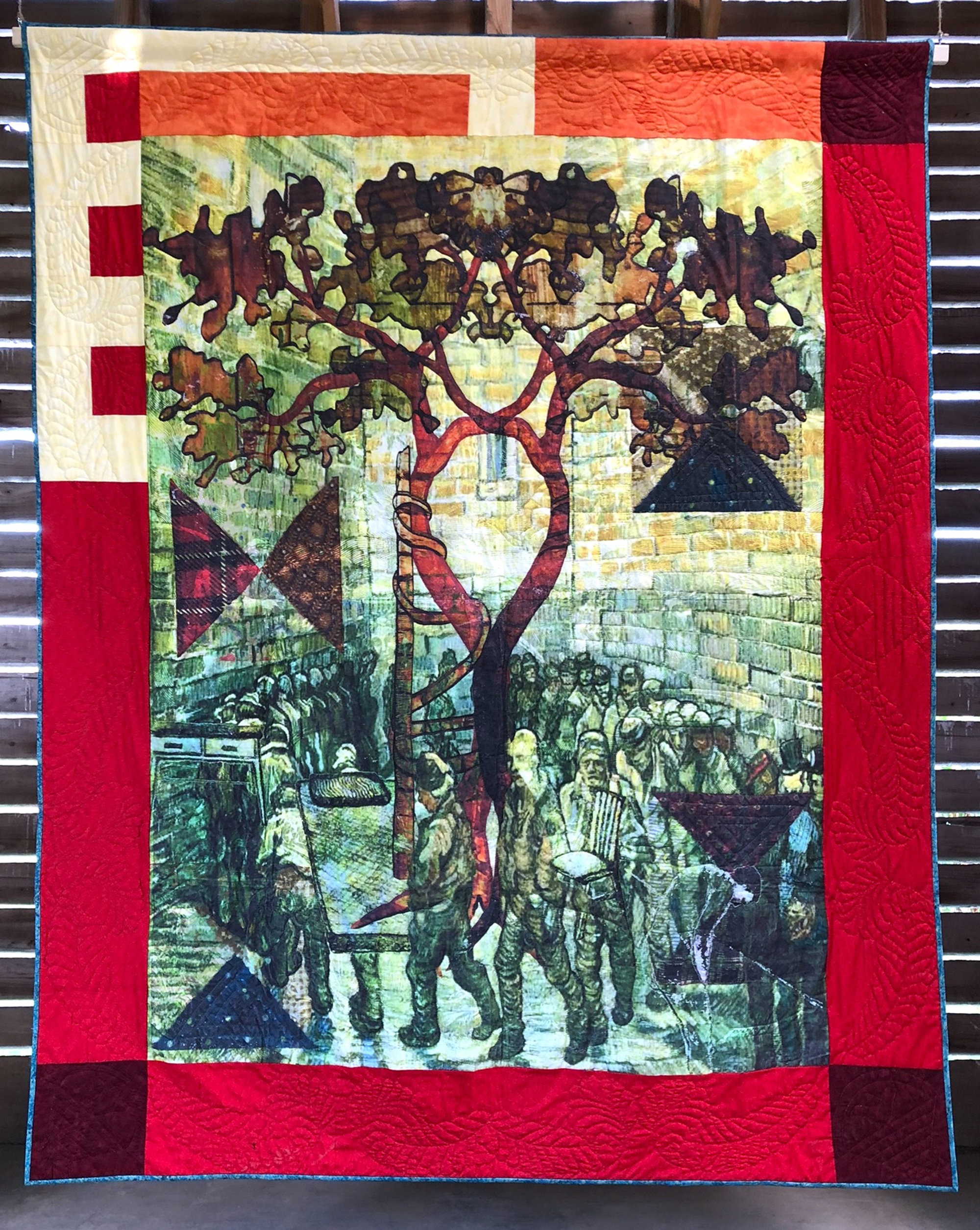

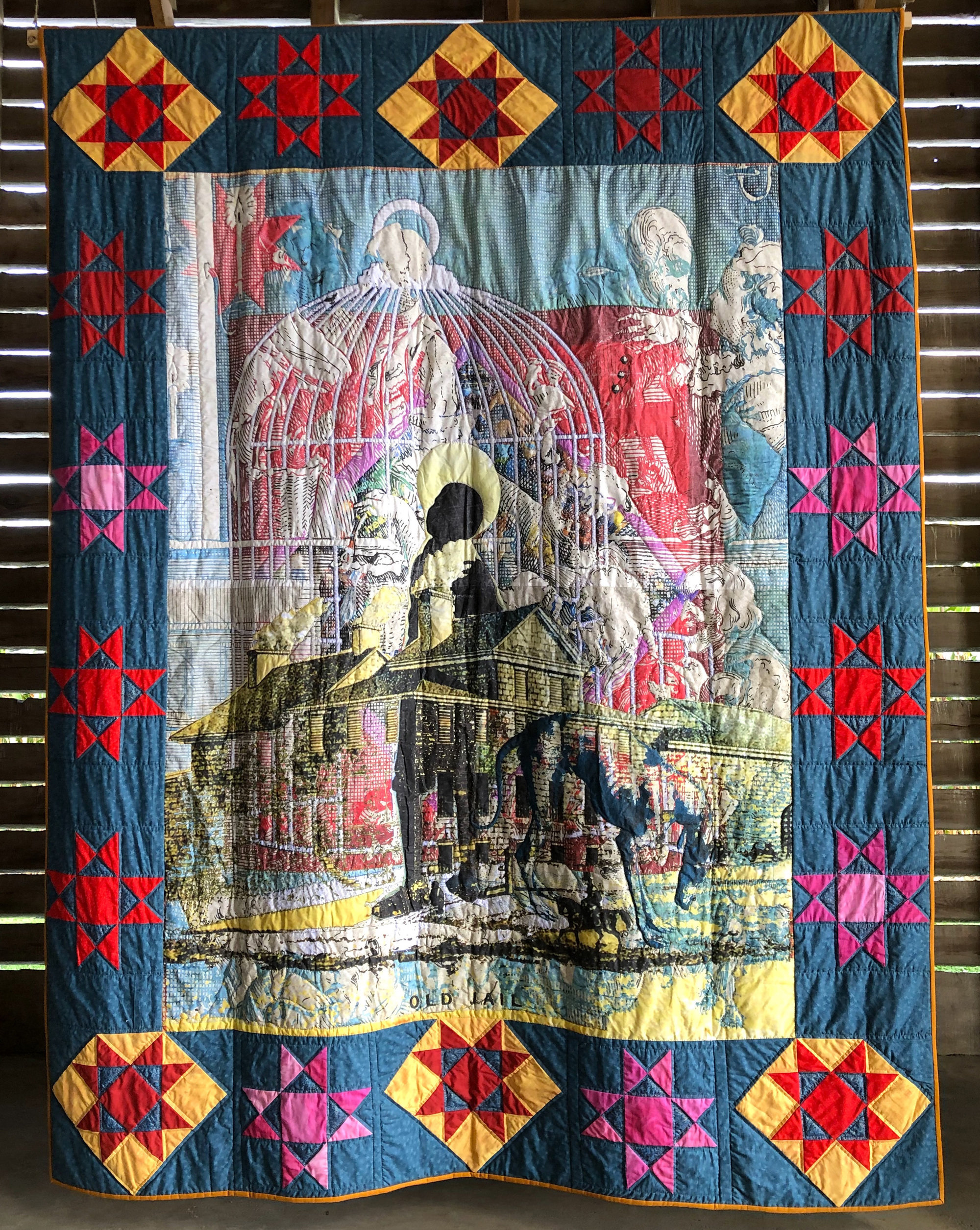

For his current piece, half of which is an art installation in a barn, he printed imagery related to incarceration in Lancaster County and elsewhere in Pennsylvania onto transparency film. To transfer the images, he placed the film over prison sheets treated with hand sanitizer. A community of Amish and Mennonite women in Lancaster then quilted the piece, which covers the entire wall of the barn.

Accompanying the quilt is a timeline of the history of incarceration in the United States, from the Transatlantic slave trade in 1619 to the First Step Act in 2018. Jasmine Heiss of the Vera Institute, a non-profit focused on criminal justice reform, worked with Krimes on the timeline, graphics, and placards in the exhibit. The imagery on the quilt includes the first jail built in Lancaster County, an old local courthouse, and a barn which served as a stop on the Underground Railroad. Superimposed on the quilt are graph lines illustrating how the African-American population in Lancaster County is disproportionately incarcerated in the state prison system. The rate of incarceration for black people from the county is nearly 14 times higher than for white people.

Also in the barn are wall-height quilts that incorporate imagery from more than two dozen workshops Krimes conducted with incarcerated and formerly incarcerated people and others. One quilt utilizes drawings by two men at a halfway house in Philadelphia. Circles are positioned like the hours of a clock-face, with symbols inside showing the cycle of incarceration. At the top, an image depicts an incarcerated father; a following image shows a mother and child alone; then the son runs away; then the son becomes an incarcerated father himself.

Another workshop participant drew a circular maze to reflect on his incarceration, and Krimes referenced this design when he designed the corn maze.

The maze has a solitary cell at the center, with seven paths to choose from, but only one way out. There are 13 dead ends—each with a road sign telling the story of someone now or formerly incarcerated. There’s the story of a young woman who committed suicide while in solitary confinement; a man who was charged with homicide for sharing drugs with someone who fatally overdosed; and a woman who had to choose between getting fired for leaving work to take a drug test required for probation or going to jail for skipping it.

The maze is designed to be disorienting and difficult to navigate, similar to the experience of being incarcerated or on parole or probation.

Though Krimes’s techniques and style are modern, his work falls partially into the category of folk art; the quilts reflect the Amish and Mennonite traditions specific to Lancaster, and the corn mazes are common there as well.

By using local art forms and traditions, Krimes said he wanted to reach an audience that is increasingly affected by incarceration.

“Major cities are cutting incarceration rates, while rural communities’ incarceration rates are going through the roof,” he said. “Racial disparities are the most drastic in these smaller communities. We all have a stake in reversing that.”

The installation is open to the public on Saturday, September 21 and Saturday, September 28, 2019, at Cherry Crest Adventure Farm at 180 Cherry Hill Road in Ronks, Pennsylvania.