The incarcerated artist Vincent Nardone stopped painting when he realized he might be annoying his cellmate. “I ended up slinging paint all over him and the room,” he said.

He picked up a ballpoint pen. “I thought, there must be a way to transform this pen into a paintbrush.” Instead of lines, he made dots. “As I got older, my hands got affected by arthritis, and it was hard to make the lines, so the dots were more convenient.”

The results are stunning. Nardone is uniquely gifted at conveying the warmth that surrounds memories when they are recalled from the grimness of prison, while also capturing the hallucinatory, time-stopping atmosphere of prison itself.

Some of Nardone’s drawings are on view at the Aldrich Contemporary Art Museum in Ridgefield, Connecticut, in an exhibit organized by Jeffrey Greene, an artist and curator who has been teaching art in prisons for decades through a non-profit called Community Partners in Action.

When the two met in 1999, Nardone had already served two decades for his role in a murder that a friend committed in Maryland. “While the person created an alibi for themselves in Las Vegas, I got rid of the body,” Nardone told me. He was 25 and was transferred to Connecticut under an interstate compact.

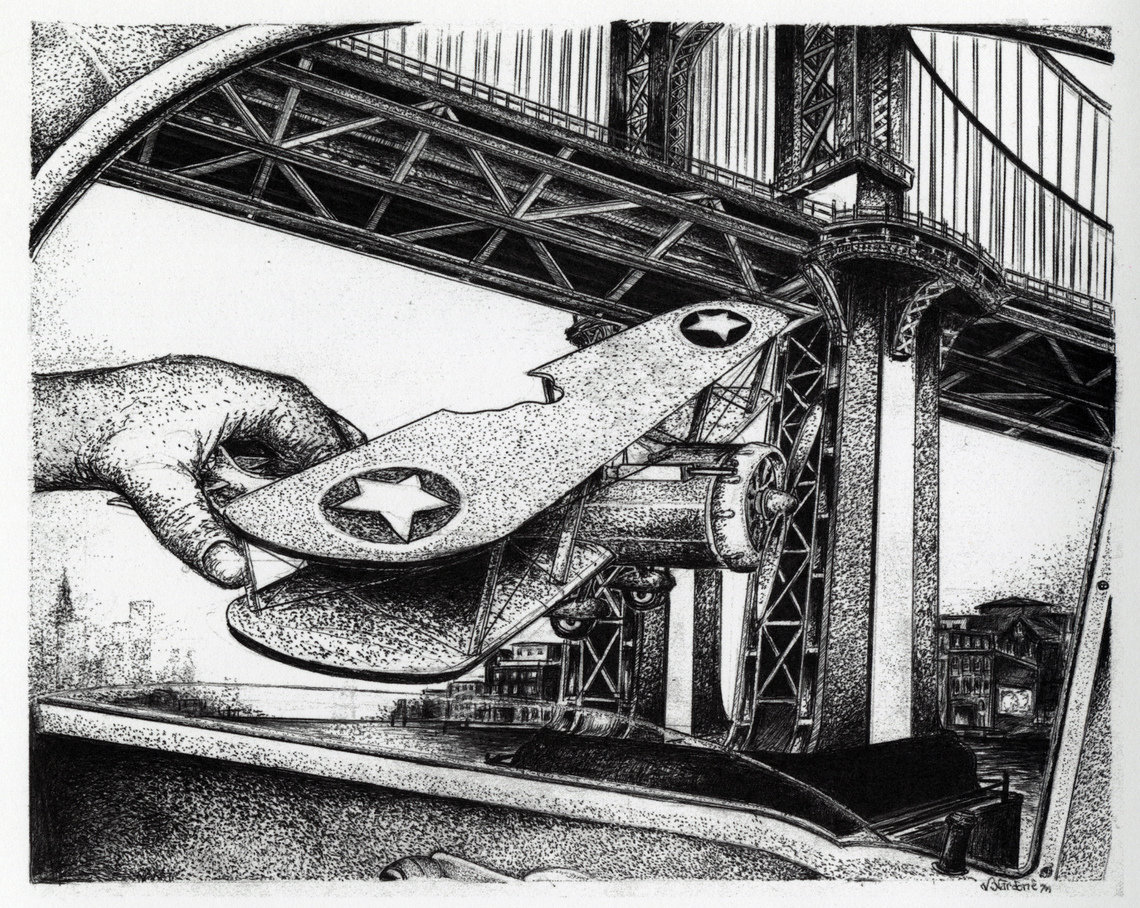

Before meeting Greene, Nardone, now 67, was in an artistic rut, producing an endless series of nautical scenes — especially clipper ships. Greene assigned him to draw an early memory, and Nardone remembered a drive he made with his parents to New York City. “He recalled how excited he was,” Greene said, “because that is where King Kong lived.”

The image shows his arm reaching out a window, his hand holding a toy plane, with the Manhattan Bridge in the background.

After that, “tons of pictures came flooding into my mind,” Nardone said. They were all from his youth in the 1950s—hyper-real, nostalgic Americana, full of soda shops and drive-in movies and cars with chrome bumpers.

But over time, his work began to address life in prison, and it grew more surreal, more symbolic, more emotional.

In “Saints, Sinners & Lost Beginners,” from 2014, hundreds of open-mouthed figures crowd towards a wall with a slot machine. “It was sort of about the appeal system,” Nardone said. “Everyone was turning a blind eye, even God. The dice are snake eyes.” In “Silence...Repent,” from 2005, prisoners appear to live in repetitious anonymity, in rings that orbit the earth. In “Last One Done in a Cell,” from 2016, a hand reaches up towards a ladder, surrounded by cell bars, as pocket watches fall from the sky: “Every watch has a time that represents when I lost someone while I was in prison. I went in with a flesh and blood family, and I came out to tombstones.”

Nardone was released in 2016, when he won an appeal; his jury had been given improper instructions. Now, he works as a fishmonger. “These pieces were my bubble, and they’re why I’m not bitter,” Nardone said. “I’m just grateful to be here. I’ll never get my life back, but I’m not trying anymore,” he said. “They ask when I’m gonna retire. I say, ‘Five minutes before they close the lid!’”