Johnny Smith spent almost 24 hours shackled in the back of a prison van—barely conscious and muttering incoherently—before he died there in 2011. A private company was hauling the 48-year-old to Florida from Kentucky to face a drug charge: possession of a single oxycodone pill.

A judge ruled that the company’s “carelessness and gross negligence” had caused the disabled construction worker’s death and awarded Smith’s children nearly $650,000 in damages.

Such lawsuits are the only recourse that families like the Smiths have against private prisoner transport companies, which remain almost entirely unregulated despite the industry's extensive history of passenger deaths and injuries. Federal agencies that are supposed to oversee the industry almost never act, and because the vans cross state and county lines, local officials can say they don’t have jurisdiction.

To this day, the Smiths haven’t gotten a dollar of what they’re owed by USG7, the company that transported their father. As they and others have tried to hold the company to account for mistreating prisoners, an investigation by The Marshall Project and The New York Times found, the brothers behind USG7 have failed to appear in court, started a new company under a different name and claimed that its documents had gone missing in a U-Haul truck.

Yet the brothers, who operated out of Florida, have held onto lucrative contracts with jails and sheriffs. And they have acquired a major stake in the largest prisoner transport firm in the nation.

USG7’s history exemplifies the lack of accountability in the prisoner transport business—even when people die. Every year, tens of thousands of Americans are arrested and extradited, or transferred, to another state where they face criminal charges. While some law-enforcement agencies move their own prisoners, those in cities like Chicago, Atlanta and Las Vegas hire for-profit extradition companies to do this job for them, on the cheap.

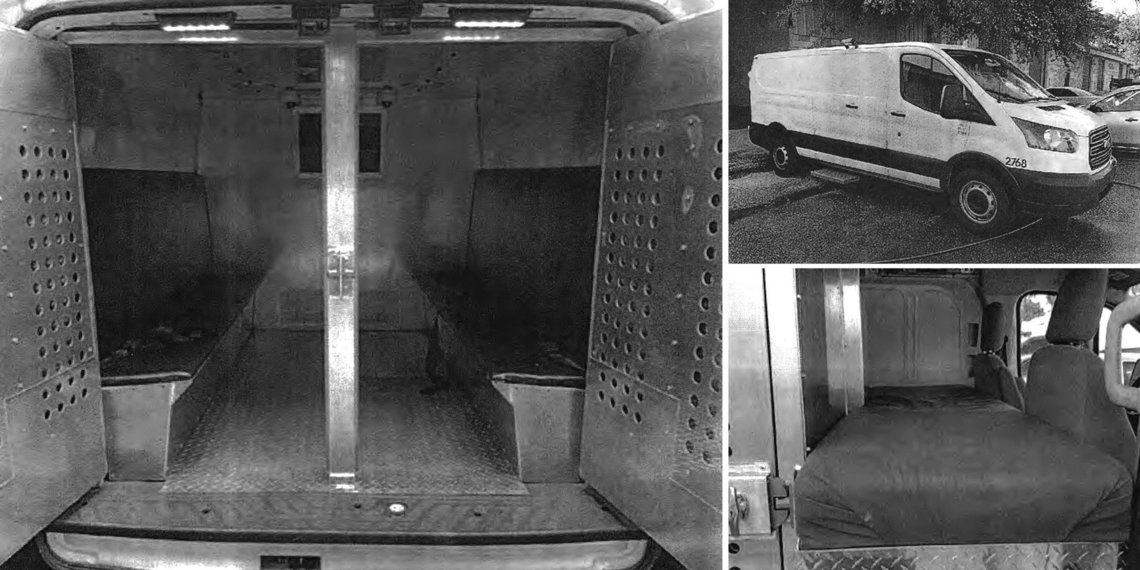

These businesses pack their vans with as many inmates as possible and spend weeks on the road making pickups and drop-offs on routes that zigzag across the country. They seat violent fugitives next to first-timers facing minor charges. The vehicles seldom stop and typically don’t have working seatbelts, air-conditioning, medical supplies or toilets, according to dozens of guards and inmates.

The handful of companies that make up this industry have been involved in more than 50 crashes, 60 escapes and 19 deaths since 2000, according to a review of lawsuits and local news articles.

After previous reports about fatalities and abuses in the prisoner transport industry, the Justice Department promised in 2016 to investigate. The status of the inquiry remains unclear. The agency declined to comment.

Last month, three members of Congress demanded information from the largest prisoner transport company about abuse and deaths aboard its vehicles, citing allegations of “inhumane and unsafe” conditions. Five of its passengers have died since 2012.

USG7, the company that was taking Smith to Florida, was relatively small, but it contributed significantly to the toll of accidents and escapes. In at least five cases, prisoners suffered severe injuries including a broken neck in crashes of the company's vans, which often traveled at dangerously high speeds and late into the night, according to accident reports and interviews with employees.

Ashley Jacques, one of the brothers who ran USG7, declined to comment when reached by phone. His brother Steven could not be reached. The family did not respond to certified letters sent to seven addresses associated with them or their companies.

Two lawyers who have represented Jacques companies declined to comment.

In depositions, the Jacqueses have said they worked at USG7 but insisted they were not its owners. But according to recently obtained emails between law-enforcement officials in Florida, as well as phone interviews with 10 of the brothers’ past employees and associates, the Jacques family operated the business.

The Smiths’ lawyers spent several years trying to collect the $650,000 judgment, but USG7 had apparently disappeared. They decided it would be too difficult to go after the owners and closed the case.

Meetings in Parking Lots

Ashley Jacques was born in South Yorkshire, England, according to a copy of his birth certificate. By 2007, he had joined the U.S. Marine Corps Reserve.

His family appears to have gotten its start in the prisoner transport industry at a company called Statewide Prisoner Extraditions. That firm’s former manager, Michael Harte, said Ashley Jacques did not follow instructions and was lax about security, and that jail employees would call in with complaints. Harte says he fired Jacques and his father, Leslie.

By 2010, the Jacques brothers and their parents had begun operating USG7. More than a dozen guards and executives interviewed by The Marshall Project said the company provided low-cost service, training its drivers only briefly before sending them out in poorly maintained vehicles.

Three former USG7 drivers interviewed by The Marshall Project said that in 2013 and 2014 they went to addresses listed for the company to try to collect back pay, but found empty offices. (In previous interactions with the Jacques brothers, guards said, they had met in parking lots, fast-food restaurants or hotels.)

At 5:30 a.m. on Aug. 24, 2010, Leslie Jacques was driving prisoners across Florida when his van slammed into a pickup truck, flinging him from the vehicle and into a river. He died. His wife, Pauline Jacques, who was in the passenger seat, survived.

The following year, a USG7 van crashed into a tree in Florida; a prisoner named Fred Ellis said that he suffered multiple broken bones in the crash and that he still has chronic back and hip pain. The company never responded to a lawsuit filed in Florida and did not pay the $400,000 that a judge awarded Ellis.

“They were not driving like they had human beings on board,” Ellis told The Marshall Project in 2016. Last December, he reached a confidential settlement with USG7’s former insurance company, his lawyer said.

The Department of Transportation found that the company was missing paperwork, including an insurance document, when the agency initially audited USG7 in 2010, according to filings obtained through the Freedom of Information Act. But the agency says that first-time audits focus on education, not enforcement. The agency rarely imposes significant financial penalties against prisoner transport businesses when they fail audits, often giving them repeated chances to improve, according to a review of hundreds of the department’s records.

The Justice Department is also supposed to regulate the prisoner extradition industry under a 2000 federal law known as Jeanna’s Act, which is aimed mainly at preventing prisoner escapes but also sets basic safety standards for their transportation.

The law has been used only once, in 2013, to penalize a transport company for allowing a convicted sex offender to escape from an unlocked van into a cornfield in North Dakota. The fine was $10,000, plus the cost of a manhunt.

The Justice Department declined to comment on Jeanna’s Act, but a spokeswoman pointed out that a private prisoner transport guard had been indicted on charges of sexually assaulting three women in his care. He pleaded not guilty in January

After a Seizure, A Plea for Help

When the USG7 van arrived at the Franklin County jail in Kentucky to drive Johnny Smith to Florida, he was so weak that jail employees had to push him to the vehicle in a wheelchair, according to police interviews.

Smith’s doctor had warned the jail that he had a variety of serious medical conditions. “I think his risk for an adverse event with extradition is high,” the doctor wrote.

Instead of heading to Florida, the van went east to pick up other passengers. In Philadelphia, Smith fell out of his seat while apparently having a seizure, according to a police report in Orange, Connecticut, where he was found dead in the back of the van 11 hours later. Smith had asked the guards for help in Philadelphia, an inmate interviewed by the police said, but after a cursory check-in, the van had driven on.

The police in Orange declined to pursue charges, saying that Smith had died of natural causes. Both guards involved in the incident declined to comment.

Smith’s next of kin decided to sue. “It wasn’t just the money,” said Michael Smith, his son. “I wanted them out of business. I didn’t want a family to go through that again.”

But when a hearing was scheduled in 2014, no one from USG7 showed up.

A Deadly Journey

Johnny Smith was picked up in Kentucky by USG7 in 2011 to be transferred to Florida. But instead of heading south, the van went east to pick up other passengers. Smith was in ill health and asked for help. Eleven hours later he was found dead. He spent nearly 24 hours in the van.

A guard checked on the prisoners, and found Smith dead in the back of the van.

CONN.

New London

5:30 p.m., March 1

Orange

New York City

PENNSYLVANIA

11 hours

in transit

Philadelphia

OHIO

Smith was picked up in Frankfort, Ky., for delivery to face a drug charge in Florida.

In Philadelphia, Smith asked guards for help. After a cursory check-in, the guards kept driving to pick up another prisoner.

12.5 hours

in transit

KY.

6 p.m., Feb. 28

Frankfort

100 MILES

5:30 p.m., March 1

Orange, Conn.

A guard checked on the prisoners, and found Smith dead in the back of the van.

6 p.m., Feb. 28

Frankfort, Ky.

Smith was picked up in Frankfort, Ky., for delivery to face a drug charge in Florida.

11 hours

in transit

In Philadelphia,

Smith asked guards for help. After a cursory check-in, the guards kept driving to pick up another prisoner.

12.5 hours

in transit

200 MILES

5:30 p.m., March 1

Orange, Conn.

A guard checked on the prisoners, and found Smith dead in the back of the van.

6 p.m., Feb. 28

Frankfort, Ky.

Smith was picked up in Frankfort, Ky., for delivery to face a drug charge in Florida.

11 hours

in transit

12.5 hours

in transit

In Philadelphia, Smith asked guards for help. After a cursory check-in, the guards kept driving to pick up another prisoner.

200 MILES

Source: Marshall Project review of police report

Note: Exact routes are not known.

The company’s lawyer, Walter Thomas, had appeared multiple times in USG7’s registration documents from 2009 to 2012, and was listed as its president in Department of Transportation filings during the same period. But in the Smiths’ case in 2014, he told the court that he’d severed ties with USG7’s management and no longer had any contact information for them.

By 2015, though, Mr. Thomas was representing a new Jacques company in a Florida lawsuit. He declined to comment.

“Yes, This is the Company That Was USG7”

Just a few months after the company stopped responding to the Smith lawsuit, the Jacqueses were moving to open another transport firm. They called it U.S. Corrections, and kept many of the same agreements with the law-enforcement agencies that had given USG7 business before, according to recently obtained emails and interviews with employees and associates.

In one email exchange, the manager of warrants and extraditions at the Broward Sheriff’s Office in Ft. Lauderdale, Florida, wrote that Ashley Jacques “requested, if possible, we execute a new contract with his company under the name of US Corrections so we can be sure the conditions of our original contract are being met by his new company.”

“Yes, this is the company that was USG7,” she says in another email.

The sheriff’s office said in a statement that it has had concerns for several years about the poor record of U.S. Corrections, but that whenever the agency puts out a request for a new transport provider, it gets little response.

In two documents from April and May 2014 signed by Ashley Jacques, he states that U.S. Corrections was assuming contract obligations previously held by USG7.

In bids for new contracts, the Jacques’s company has written that “U.S. Corrections is a new company by name but not by existence, experience, and management.”

But the Jacques brothers have maintained in multiple court filings that USG7 and U.S. Corrections are separate entities. And that has been enough to thwart lawyers trying to collect judgments.

Businesses often set up limited-liability companies, or L.L.C.'s, and in some states, these companies don’t have to disclose the names of the people behind them.

A person named Graham Wright, who signed at least one document in 2014 as the “owner” of USG7, could not be found. None of the employees interviewed said they had ever heard of him.

U.S. Corrections has been registered in North Carolina, Tennessee or Delaware, according to various filings, but it has operated from Florida, according to those who have worked for the company. Lawyers said they have been unable to find the Jacques family because rather than list their street addresses in court documents, they often used post-office boxes.

How do we know the two companies are functionally the same?

Take a look at these documents:

One of USG7’s biggest clients, the sheriff’s department in Fort Lauderdale, Florida, says so.

Ashley Jacques asks the sheriff’s department to transfer USG7’s contract to his new company, U.S. Corrections.

U.S. Corrections uses USG7’s email address and identity number.

They tell their clients that U.S. Corrections is taking over USG7’s contracts.

In bids for new business, U.S. Corrections says it employs the same people and uses the same equipment as USG7.

Jason/Terrence,

USG-7 changed name and ownership and is now operating under the name of US Corrections. I am not aware of any new contracts being signed or any old ones being amended. Apparently USG-7 moved all operations to California and all accounts under USG-7 were inherited to US Corrections.

Did either of you receive this information? If not, should we stop using US Corrections until a contract is signed?

I appreciate your prompt attention.

Kathy Moniz, Manager

Broward Sheriff's Office

Warrants/Extraditions Unit

Terrence,

... Mr. Jacques further requested, if possible, we execute a new contract with his company under the name of US Corrections so we can be sure the conditions of our original contract are being met by his new Company. ...

Thank you,

Kathy Moniz, Manager

Broward Sheriff's Office

Warrants/Extraditions Unit

July 28, 2014

Dear GRAHAM WRIGHT,

This notification is being sent as a result of an FMCSA online USDOT Number PIN request for your USDOT Number XXXX165. The following information is provided:

Name of Requestor: Graham Wright

Email Address to which PIN was provided: info@usg7.com

... WHEREAS, the Assignor, USG7, is withdrawing operations and affiliations with any involvement having to do with Prisoner Transportation and/or Extraditions as of April 1st, 2014. As of this date the Assignee, U.S. Corrections shall assume the assignment, responsibility, and provide services to all existing transportation contracts in place between USG7 and Agencies involved. ...

... The Assignee, “U.S. Corrections” shall assume no liability for any services or lack thereof provided prior to the date of agreement, April 1st, 2014. Such liabilities include but are not limited to, complaints, missed pick-ups, releases, lawsuits, or any other business related issues. ...

ASSIGNOR:

United States Group 7 (USG7)

Name: Graham Wright

Title: Owner

ASSIGNEE:

U.S. Corrections, LLC (USC)

Name: Ash Jacques

Title: Director

... CORPORATE BACKGROUND AND EXPERIENCE

U.S. Corrections is a new company by name but not by existence, experience, and management. The name U.S. Corrections, often referred to as U.S.C., was formed in January of 2014 after an existing company decided to leave the prisoner transportation industry and focus their efforts elsewhere. The management team of the existing company’s transport unit, which had been around since 2008, had an agreement with the owners to continue to employ all transport staff, purchase all vehicles and equipment, and launch the U.S. Corrections that you now know today. ...

Ashley Jacques remains a member of the Marine Corps Reserve. He’s been deployed to Iraq and currently serves about one weekend a month and two weeks a year as a military police officer in Brooklyn, according to a spokesman for the Marines.

He has signed some business correspondence “Capt. Ash Jacques.”

“Slap a New Name on the Side”

About two years ago, U.S. Corrections was acquired by Prisoner Transportation Services, the nation’s largest extradition outfit. The Jacques brothers received a combined 11.25 percent share of P.T.S., and Steven Jacques was given the title of chief transition officer, according to court records.

In a statement, the company said that the Jacqueses “neither have the right or ability to manage or control P.T.S. nor are they involved in the company’s daily operations.”

“Make no mistake, P.T.S. remains committed to doing things right and working to raise the standards of service across the entire industry,” the statement says.

The company said it did not assume the liabilities of U.S. Corrections and had no relationship with USG7.

But one lawyer whose client recently brought a lawsuit against U.S. Corrections asserts that the P.T.S. deal was part of a recurring effort by the Jacques family to evade responsibility.

“Slap a new name on the side of its business and escape its day of reckoning,” the lawyer, Frank Hedin, wrote in a June email requesting evidence for the lawsuit, which proceeded for much of last year in federal court in Ft. Lauderdale.

The plaintiff said that in 2015, he was transported by U.S. Corrections for 52 hours inside a cage in a windowless van with no ventilation, no way to lie down, not enough water and only an empty bottle to urinate in.

The judge initially said she needed to determine whether the company had avoided liability through “a corporate transformation in form only.”

But in later depositions and filings, the Jacques brothers said they could not provide information about the company’s history because they had mislaid their records.

In one instance, they claimed that U.S. Corrections’s records are on a flash drive that they could not find. Other documents, they said, were on a rented truck that went missing. They have also claimed that it would take precisely 5,528 hours to gather information about past inmate transports.

In late December, the judge in the case ruled that the lawsuit could not be turned into a class action, because it would be too difficult to define who had been harmed by U.S. Corrections, when and how. The plaintiff agreed to a confidential settlement with the company, and the question of who is liable for its debts remains unresolved.

Months after the merger of U.S. Corrections and P.T.S., the company was moving a man to Florida from Virginia to face a 9-year-old charge of stealing a pearl necklace during a burglary. Other passengers said he pleaded in vain for help. He died en route.