The sun has barely risen over Miami, and Dale Brown loads an orange shopping cart with everything he owns. Through the morning’s swampy heat, he pushes the cart to the edge of the railroad tracks, where he hauls the items one at a time into some overgrowth and covers them with branches. His tent from Wal-Mart, meticulously rolled and packed. A garbage bag with clothes and a blanket. He unscrews the lid to a plastic gallon jug and empties his urine into the brush.

“You feel like an animal,” says Brown, 63.

This industrial neighborhood just beyond Miami’s far western edge is home to lumber yards, auto parts warehouses, and, in recent months, roving encampments of homeless sex offenders. This summer, Brown and a half-dozen other men were living beside a chain-link fence outside a hardware company. Five blocks away, more lived in tents and makeshift shacks. And 12 blocks from there, about a dozen arrived in cars each night.

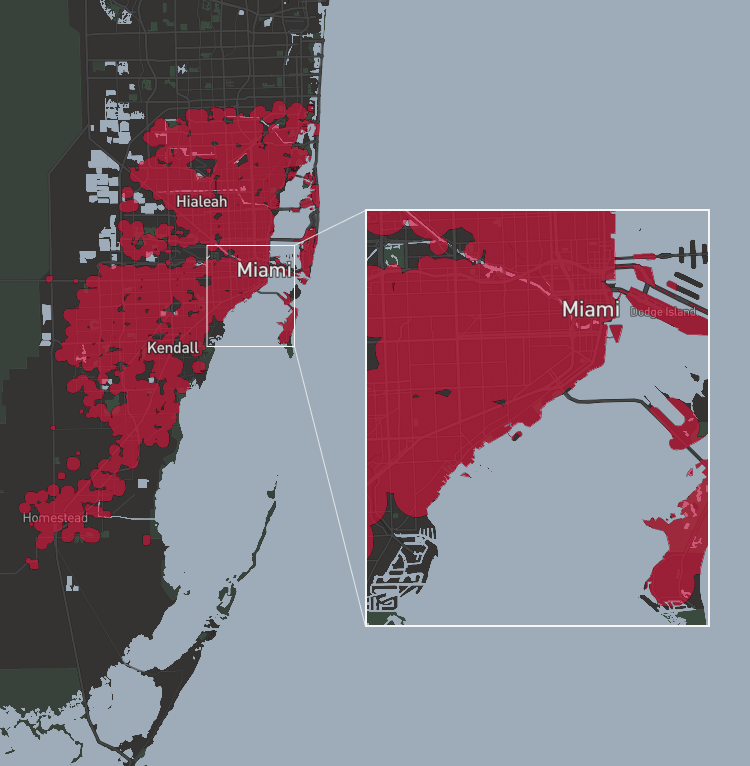

A combination of federal, state and local laws has rendered almost all of Miami-Dade County off-limits to sex offenders with young victims. The feds say they’re not allowed in public housing. The state says they can’t live within 1,000 feet of a day care center, park, playground or school. The county says they can’t live within 2,500 feet of a school. In a place so densely populated, forbidden zones are everywhere. And in the narrow slivers of permitted space, affordable apartments with open-minded landlords are nearly impossible to come by.

With so few options, almost 500 of Miami-Dade’s 2,200 registered sex offenders are homeless, according to law enforcement data. And a county ordinance amended earlier this year has essentially made that illegal, too—police can now arrest sex offenders for camping on public property. They’re also not allowed in homeless shelters. “You have one law that says you can’t live inside and another law that says you can’t live outside,” says Valerie Jonas, an attorney representing sex offenders in a lawsuit against the county brought by the ACLU and Legal Services of Greater Miami.

The suit claims that the residency restriction has left the sex offenders homeless, retroactively layering additional punishment atop their original sentences, which is unconstitutional. The county argues that the law is a regulation, not a punishment, saying in court papers that “if Plaintiffs have suffered any alleged harm, it is a result, in whole or in part, of their own conduct.”

Those subject to the residency restriction have committed a range of crimes, from being in a “Romeo and Juliet” relationship to downloading child porn to sexual assault. Brown, a former teacher, molested students in his care. Darrell, 46, who asked to be identified by his first name only, raped his stepdaughter over four years starting when she was 12. It’s easy to see why lawmakers would want to banish these men to the farthest reaches of society.

But beyond the moral arguments about where sex offenders should live are the practical considerations of being human: They need to eat and sleep. They need a little money to get by. They need somewhere to pass the hours. And so they begin and end each day with a question: How do you build a life in the shadows of a society that no longer wants you?

First, you seek a place to stay where the police might leave you alone for a while. So you ask around. Text some guys you know. Scroll around the county’s interactive map to check an address against schools, daycares and parks. Find a corner or overpass where you can pitch a tent or park a car.

Once you find a good spot, “that’s like a military secret,” says “Stretch,” 26, who asked to be identified by his nickname because he fears for his safety. Stretch sleeps in a doorway on Brown’s corner. He and his friend, Michael Williams, 51, moved here from a loading dock in Opa-Locka, where they lived for five days before the police ran them off. Williams says he hated losing that place—a nearby gas station had a bathroom, and an overhang shielded them from rain. Like many homeless sex offenders, Stretch and Williams have families they could stay with, but they live too close to schools.

Housing restrictions for certain sex offenders in Miami-Dade County

State law

Miami-Dade law

During the rainy season, it thunderstorms almost daily. Some days, Darrell bikes in the rain to his job, gets drenched during his 12-hour shift washing cars and trucks, then returns to his damp tent at night. During storms, he prays he doesn’t get struck by lightning.

“There’s no mercy out here for us,” he says.

Any adult convicted of a sex offense in Florida must register their address with police; the information is displayed on a publicly-searchable government website. Homeless offenders must update their address each time they move, or every 30 days if they remain in one spot. They also must update their driver’s license information at the DMV with every move. Using public transportation, the process in Miami—which involves getting to the registration office in the suburb of Doral—can take up to two days.

One man at Darrell’s encampment lost his job at an elevator manufacturer, he says, because he missed too much work keeping his address updated. His boss hired him back, but he wonders what will happen next time the police come to move the men along.

Most offenders aren’t only navigating residency and registration laws. For years, many are on probation, which comes with its own requirements, including a curfew—usually from 10 p.m. to 6 a.m. An ankle bracelet and GPS box, which must be charged every day, transmit their movements to a probation officer.

Noncompliance brings the threat of jail time. Failure to register is a felony. Registering at one address and staying at another is a felony. Failure to report a new email address, tattoo, car, boat or job is a felony. And an offender on probation who isn’t in place during curfew, or who doesn’t charge his GPS box, or misses appointments or breaks any of dozens of other rules, could end up back in prison for years.

When they passed the residency restriction nearly a decade ago, Miami-Dade county commissioners said it was meant to protect children from sexual predators, “who present an extreme threat to the public safety.”

But offenders claim it’s doing no such thing. After all, the 2,500-foot rule and curfew only apply at night, when most kids are home asleep. “You can, in the daytime, go wherever you want,” says Brown, who spends his days at the mall or the library charging his GPS box, since there’s no electricity at his encampment. “It’s illogical,” he says. “Any place you go, children are everywhere.”

Part 2

By the Book

Across the country, thousands of cities and towns restrict where sex offenders can live; they commonly use a buffer of 1,000 to 2,000 feet from places children congregate. Florida has long been ground zero for these statutes: In 1995, it was the first state to enact one. The law came at a time when parents across the country were electric with fear over a series of high-profile child kidnappings, sexual assaults and murders. Jacob Wetterling, Adam Walsh and Megan Kanka had become household names, and Congress memorialized them with the first federal laws establishing sex offender registries and other tough measures.

Then in 2005, Florida faced its own galvanizing tragedies: the back-to-back murders of two young girls by convicted sex offenders. In the most high-profile case, 9-year-old Jessica Lunsford was abducted from her home in west Florida, then raped and murdered by a child molester with a long criminal history who lived nearby. In response, Miami Beach passed its own law banning sex offenders from living near children, one of the first cities in the nation to do so. Officials set an exclusion zone of 2,500 feet, or about a half a mile, from schools, parks and child-care centers. On a 7-square-mile island, the message was clear: Sex offenders are not welcome here.

More than 100 nearby localities, including Miami-Dade County, followed suit. The man most responsible for all of these laws is Ron Book, one of the state’s most powerful lobbyists. Book specializes in lobbying state legislators on behalf of municipalities, and his outsize influence with lawmakers up and down the state means he’s used to getting his way.

For Book, the public shunning of sex offenders is a personal mission. In 2001, his daughter Lauren revealed she had been raped and abused by her family’s nanny for years, starting when she was 11. The nanny, Waldina Flores, pleaded guilty in 2002 and remains in prison. Ever since, Lauren has devoted herself to education and outreach on childhood sexual abuse, while Ron has focused on legislating the perpetrators of these deeds further into society’s margins.

“Everybody knows that Ron Book is the key to the county doing anything on sex offenders or trying to change this law to any degree,” said Brandon Buskey, an ACLU attorney suing the county over the ordinance. “If he were to say tomorrow, ‘I think we need a different path,’ I guarantee you the laws would be off the books.”

In 2010, the county passed the Lauren Book Child Safety Ordinance, which prohibits sex offenders from loitering within 300 feet of places children congregate “with the intent to commit a sexual offense.” It also consolidated a jumble of local rules, applying the 2,500-foot residency restriction only to schools and not to parks or other places.

By limiting the residency restriction, county officials hoped to address an embarrassing problem: About 100 homeless sex offenders were living on a spit of land underneath the Julia Tuttle Causeway, which connects mainland Miami with Miami Beach across Biscayne Bay. With no place else to send them, prisons were releasing people directly to the bridge. To get there, they had to walk along the six-lane roadway with their supplies, swing over the guardrail and climb down.

They called it “Bookville.”

As media came from all over the world to chronicle how these men had been virtually cast out to sea, police moved to shut the camp down.

But even with the new ordinance, it was no easier to find a place to live. A few years later, almost 300 sex offenders were registered to the blocks surrounding Northwest 71st Street and 36th Court in northern Miami-Dade County. There were no toilets and no running water. Nearby business owners complained about the stench and the trash. In the summer of 2017, health officials began documenting sanitary violations at the site; later that year, they told the mayor’s office to shut it down.

Officials were determined to take a compassionate approach, they said. Vans from the Homeless Trust, a local quasi-governmental organization, brought career coaches and outreach workers to help people find jobs and places to live.

In what critics see as a dark irony, the chairman of the Homeless Trust is Ron Book.

“He is the head of an organization charged with finding housing for the homeless. And he helped draft, helped pass, and supports a law that actually makes people homeless,” says Buskey of the ACLU.

In the weeks leading up to the camp’s closure, the Trust announced it would provide a security deposit and several months of rent to anyone who found a home. But by all accounts, almost no one did. According to Olga Golik, an attorney for a Homeless Trust contractor that provided assistance to the offenders, only one person found housing—and only because the landlord was himself a sex offender. “He was a little bit more sympathetic,” Golik says. Deputy Mayor Maurice Kemp says more than one person was placed but did not cite a number.

That left hundreds of sex offenders at the site. So officials devised a new plan to force them out: They would make it illegal to stay there.

Camping on county property was already forbidden, with an exception for the homeless; police had to offer shelter before arresting them. Because sex offenders are not allowed in public shelters, they were shielded from arrest for camping. In January, the Board of County Commissioners amended the ordinance; police could now arrest sex offenders on sight for sleeping overnight in a tent or shack on county land.

One May morning, police descended on the 71st Street encampment with their bullhorns and a pre-recorded message: IMMEDIATELY GATHER YOUR PERSONAL BELONGINGS AND VACATE THE AREA PEACEABLY. Only Brown and a handful of other offenders remained; everyone else had fled to other street corners.

As chairman of the Homeless Trust, Book pushed for the ordinance. At a board meeting and in public testimony, he described the law as a “pressure point” to urge homeless offenders into housing. These men weren’t accepting the Trust’s offers for housing assistance, he said, because they weren’t motivated to leave.

When asked about the dozens of sex offenders who say that they have worked with the Homeless Trust to find an apartment but failed, he says: “Tell them my response was they're lying.”

The Marshall Project reached out to the 13 sitting county commissioners, including Xavier Suarez, who was elected after the 2,500-foot rule passed. “We need to find a better solution than to say, ‘There is no place they can legally exist,’” he says. When asked what a better solution might be, he deferred to his colleagues whose districts include more homeless sex offenders than his does. No other commissioner agreed to comment.

Olga Vega, spokeswoman for Commissioner Jose Diaz, the prime sponsor of the 2,500-foot rule, suggested we speak to Ron Book.

Part 3

Cat and Mouse

When the police come to break up a camp, you see the blue and red lights first, shining through the walls of your tent. “They tell you, ‘pack up or you go to jail,’” Darrell says. “They want you out of the area, off the grid. They don't want you nowhere near nothing.”

Miami-Dade police say they haven’t arrested any homeless sex offenders for camping under the new ordinance. But they do threaten people with arrest if they don’t move. The towns and cities that compose the county, many with their own police forces, seem to have varying degrees of tolerance for sex offenders who set up camp in their public spaces.

One night earlier this summer, police from Hialeah, just west of Miami, came to tell Brown and others that they couldn’t camp on the west side of 37th Avenue. That was in their jurisdiction. So the men moved to the east side of the street.

“We’re like nomads,” Brown says.

Beyond chasing sex offenders from street corners, police must also verify that they’re staying at their registered locations. Most nights a team from the county’s Sexual Predator and Offender Unit drives around with a list of addresses, finding a dozen or so each time.

In a deposition in the ACLU case, a county police lieutenant said that many sex offenders who can’t find a proper home far enough from a school simply ignore the ordinance: They register as homeless and then live where they want. If they’re no longer on probation, it’s hard to prove they’re not “living” at their registered spot since they have no GPS box and no curfew.

Not knowing where these people actually live makes it nearly impossible for police to keep an eye on them. That’s one of the reasons that many criminal justice researchers argue these laws don’t protect anyone. In fact, they say, setting sex offenders up to be homeless, difficult to employ and cut off from family makes society less safe.

Studies in a half-dozen states all found that residency restrictions didn’t prevent sex crimes. But they do increase homelessness and transience—and offenders who move a lot are more likely to commit crimes than those who don’t, research shows.

Katy Sorenson, a retired Miami-Dade county commissioner who co-sponsored the 2,500-foot ordinance, says learning about some of this research has prompted second thoughts about the law. “We were looking for a solution to a problem,” she says. “But obviously it’s created additional problems. You just can’t have people being homeless on the street without anywhere to go and no options. It’s like people being without a country.”

Sorenson argues that lawmakers should reconsider residency restrictions and “re-focus on where the problem really is.”

The problem is most often close to home: Research shows that more than 90 percent of sexually abused children know their abusers. These are relatives, teachers, clergy and other trusted figures who have access to kids in their own homes, schools and churches. The real risk to children is “social proximity, not residential proximity,” says Jill Levenson, a social work professor at Barry University in Miami-Dade County and a leading researcher on this population. The laws misdirect resources, and parents’ attention, towards “stranger danger” cases, which are very rare, rather than potential abusers in the family’s circle, Levenson says.

Citing such research, courts have struck down some residency restrictions. In 2015, California’s high court invalidated that state’s law, calling it “unreasonable, arbitrary and oppressive.” (The lead plaintiff in that case had AIDS, throat cancer and diabetes; he was jailed on a parole violation because he did not register the address of his hospital bed.) More recently, the U.S. Supreme Court left in place a federal ruling that struck down aspects of Michigan’s sex offender school zone restrictions. And local ordinances—including one this year in Fort Lauderdale—have been found unconstitutional, too.

“We have reason and science on our side,” says Jonas, the civil rights attorney, who has represented sex offenders in the Fort Lauderdale suit and the ongoing Miami-Dade lawsuit. “All they have is panic.”

Book dismisses the science, saying that sexual abuse is so under-reported as to render any data about it meaningless. “These so-called ‘experts’—they opine that I don't have studies to show [anything] different about recidivism rates,” he says, referring to the rate at which offenders commit other crimes. “I got common sense.”

The Marshall Project attempted to reach victims of Brown and others featured in this story through the Miami-Dade State Attorney’s Office, but a spokesman said the victims’ contact information was outdated.

Homeless sex offenders in Miami-Dade County have little reason to hope their circumstances will change anytime soon. Even if the suit against the county succeeds, the ruling would only apply to those who committed crimes before the original ordinance passed in 2005. Barring other legal action, someone like Stretch, who pleaded guilty in 2012, will still spend the remainder of his life displaced.

Stretch says he doesn’t want to get too comfortable living on the street. So as night fell one day in June, he unfolded a chair in a doorway near Northwest 43rd Street and 37th Avenue. He sleeps like that, feet propped on a ledge.

Williams assembled a folding cot next to him. After more than 10 years in and out of prison, he was just a few months from finishing probation. When he imagined the relative freedom, he said, “It’s like a ton of bricks taken off me. It feels so good.”

But one evening soon after, Williams didn’t come back.

On the previous night, according to his probation officer, Williams’ GPS box registered that he was not at his site during curfew, and he went to jail. Williams says he had walked about a mile to the closest gas station bathroom. A corrections department spokesman said Williams was gone for two hours and ignored warnings from his box to return home. Williams has since been transferred to a prison near the Georgia border and is scheduled to be released in February.

The nightly ritual of making camp continues without him. Brown and several others carry their tents and trash bags out of the brush and begin setting up for the night. A fluorescent orange sign—UTILITY WORK AHEAD—is upended, and someone is using it as a makeshift nightstand, his glasses folded on top. Brown looks around at the broken glass sparkling in the streetlights and the port-o-potties locked behind a chain-link fence at a nearby warehouse, just out of reach. “When we were at 71st Street, we thought that was a really bad place,” he says. A half-dozen corners later, with likely many more ahead, he realizes, “that was the best place we were at so far.”

Text Beth Schwartzapfel

Video and Photo Emily Kassie

Additional Cinematography Aidan Shipley and Dominic Easter

Additional Editing Elise Coker and Juhui Kwon

Drone Photography William Ciani

Creative Direction and Design Alex Tatusian and Emily Kassie

Development and Design Katie Park, Gabe Isman and Anna Flagg

Motion Graphics Yaniv Fridman

News Clips CBS Channel 4, ABC News, France24

In December, a federal judge in Florida ruled against the group of homeless sex offenders that filed suit against Miami-Dade County. The sex offenders argued that the county’s housing rules layered additional punishment atop their original sentences, which the Constitution forbids. But Judge Paul Huck found that the residency restrictions were not punishment and were “rationally related to the goal of protecting children.”

The offenders were homeless for many reasons beyond the residency restrictions, Huck wrote, including that it’s difficult to find housing in Miami in general, especially with a criminal conviction of any kind.

Attorneys for the sex offenders say they are considering their options, including whether to appeal the ruling.