Late one spring night in 1984, the doorbell rang at the home of Norman and Mary Jane Stout. The Stouts, married thirty years, with three grown kids, lived in Guernsey County, Ohio, about a hundred yards off Interstate 70. Norman was a heavy-equipment operator; Mary Jane, who once worked as an office manager, was a collector of Holly Hobbie plates and figurines. They were at the kitchen table, paying bills. Norman opened the door to find two men, who looked to be in their mid-twenties. They said that their car had broken down on the highway and asked to use the telephone.

Norman invited them in, then watched as one of the men, after finishing the call, took out a handkerchief and wiped off the receiver. The two men—their names were John David Stumpf and Clyde Daniel Wesley—pulled guns. “Oh, by the way, this is a stickup,” Wesley said. When Norman rushed at Stumpf, Stumpf shot him twice in the head; the first shot, Norman later recalled, hit “the bridge of my glasses, right between my eyes.” He lost consciousness and fell to the ground. Afterward, one of the robbers shot and killed Mary Jane. Norman came to in time to hear the men’s voices in another room, and then the shots that killed his wife. But he couldn’t see who fired the gun.

Stumpf and Wesley were both charged with aggravated murder, and were prosecuted separately at the Guernsey County Courthouse. Stumpf’s case went to court in September, 1984. A county prosecutor, urging the death penalty, argued that Stumpf had shot Mary Jane : “Believing that he had killed Mr. Stout, this defendant then turned the same chrome-colored Raven automatic pistol upon Mary Jane Stout as she sat on the bed and shot her four times. Three times in the left side of the head and neck and one time in the wrist, obviously in order not to leave anyone available to identify him.” Stumpf was convicted and sentenced to death.

Seven months later, the prosecutor returned to court for Wesley’s trial. Again seeking the death penalty, he argued this time that Wesley had fired the fatal shots : “Believing that he had killed Mr. Stout, John David Stumpf pitched the gun aside.” At that point, the prosecutor continued, “this defendant, whose own gun was jammed, picked that chrome-colored Raven up and, as Mrs. Stout sat helplessly on her bed, shot her four times in order to leave no witnesses to the crime.” Wesley was convicted and sentenced to life.

Several years ago, a lawyer contacted me about a case in which he said prosecutors had argued contradictory theories of a crime. Looking into the subject, I didn’t find much—a few law-review articles and the occasional news story. The author of an article from 2001, a professor emeritus at Villanova University’s law school named Anne Bowen Poulin, told me that when she began her research a colleague said to her, “This is stupid. It never happens.” The next day, Poulin got a call from a former student, now a defense attorney, who had just such a case, in Philadelphia. “It does happen,” Poulin said. “And probably more often than we’d like to think.”

There’s no saying exactly how often. But, in a recent canvass of court rulings, I turned up more than four dozen cases, from California to Massachusetts, in which the defense attorney argued in an appeal that the prosecution had told conflicting stories about the crime. Prosecutors have offered contradictory theories about which defendant stabbed someone with a knife, or chopped a woman’s skull with a hatchet, or held a man’s head underwater. The most common scenario involves a fatal shot: the prosecutor puts the gun in the hand of one defendant, then another. Under the legal principle of accomplice liability, a defendant can be convicted of murder without being the killer. But, if the prosecutor says that a defendant pulled the trigger, it’s easier to ask a judge or a jury for a death sentence. At least twenty-nine men have been condemned in cases in which defense attorneys accused prosecutors of presenting contradictory theories. To date, seven of those twenty-nine have been executed.

Listen to an audio version of this story:

More often than not, judges who are confronted with inconsistent prosecutions have affirmed convictions, while, at times, expressing distaste for the tactic. The descriptions applied by judges include “unseemly,” “unseemly at best,” “troubling,” “deeply troubling,” and “mighty troubling.” “The state cannot divide and conquer in this manner,” a federal appeals-court judge wrote in one Georgia case, in which the court threw out a defendant’s conviction on other grounds. “Such actions reduce criminal trials to mere gamesmanship and rob them of their supposed purpose of a search for truth.”

In 2004, the Sixth Circuit Court of Appeals overturned John David Stumpf’s conviction in the murder of Mary Jane Stout, writing, “Inconsistent theories render convictions unreliable.” The state appealed, and on April 19, 2005, the Supreme Court heard oral arguments in Stumpf’s case. Justice David Souter said, of the prosecution’s contradictory theories, “It has to be the case that one of those arguments, if accepted, would lead to a false result.” Souter asked how the use of conflicting arguments could square with due process. Justice Antonin Scalia said that he saw no such problem: “Due process doesn’t mean perfection. It doesn’t mean that each jury has to always reach the right result.” Scalia’s language was so blunt that even Ohio’s State Solicitor saw a need to soften it. “I agree with that, Your Honor, and I hate to argue against my position, so I do this gently,” he said. “One of the old saws of American law is, it’s better one guilty person should go free than that one innocent person should be punished.”

Two months later, the Supreme Court issued a unanimous opinion, written by Justice Sandra Day O’Connor, affirming Stumpf’s conviction while avoiding the due-process question. Under Ohio’s law on aiding and abetting, Stumpf could have been convicted of aggravated murder no matter who fired the gun. The question, the Court determined, was whether the prosecution’s inconsistency should invalidate Stumpf’s death sentence. The Sixth Circuit had not tackled that issue, so the Supreme Court sent the case back for an answer. To this day, the Supreme Court has not ruled squarely on the validity of conflicting prosecution theories.

Cases like Stumpf’s have long offered the courthouse equivalent of what the counsellor to the President Kellyanne Conway described, in January, as “alternative facts.” In 1935, the Supreme Court said that a federal prosecutor “is the representative not of an ordinary party to a controversy, but of a sovereignty,” and that his “interest, therefore, in a criminal prosecution is not that it shall win a case, but that justice shall be done.” A prosecutor who presents contradictory theories risks violating this vision of his role. In “Do No Wrong,” a 2009 book about legal ethics, Peter Joy and Kevin McMunigal wrote, “Public respect and trust in our criminal justice system will suffer if factually inconsistent charges are pursued that result in an innocent person being convicted.” “Imagine,” they continued, how jurors “would feel about the prosecutor and the criminal justice system” if they learned that the prosecutor had told them one story of the crime—and then told another jury the opposite.

In the summer of 2000, Demetrius Pascall was twenty-seven—a large man, six feet tall, three hundred and two pounds, who played the bass guitar at Faith and Hope Ministries in Wellston, Missouri. He had been married two years, and he and his wife were looking to buy their first house. At about 10 P.M. on July 30th, he pulled into the parking lot of a Schnucks grocery store in St. Louis. The store, open twenty-four hours, was busy.

Pascall was driving a white 1990 Lincoln Continental with a blue ragtop. He dropped off a cousin at the store’s entrance, then pulled alongside a couple of women walking to their car. According to police, as he chatted with one of the women, his Lincoln caught the attention of four men nearby, in a black Nissan Pathfinder. Antoine Bankhead, who was eighteen, and Martez Shadwick, who was nineteen, had been friends since middle school. Bankhead had two children and had flipped burgers at Wendy’s; Shadwick had a daughter and had worked there, too. Bankhead told me that he had met the other two men, Alvin Washington and I. V. Simms, who were both eighteen, more recently.

Two of the men approached Pascall, wearing black baseball caps and gold bandannas, which left only their eyes exposed. The caps had lettering affiliated with a local gang. One of the two pulled a pistol, a .380 semiautomatic. They told Pascall to get out of the car and demanded his jewelry. Pascall resisted and ran toward the grocery store. A bullet hit him in the left side of his chest, and, as he reached the entrance, he collapsed into the arms of a woman who was shopping with her son and three grandchildren. “Somebody help me,” she heard him say. The gunman and the second robber jumped into Pascall’s Lincoln and sped away. Pascall died at Saint Louis University Hospital, shortly after midnight.

Detectives interviewed at least eighteen eyewitnesses to the murder. Aside from race—both robbers were black—their descriptions were not consistent. One witness described both men as four feet eleven. Another said that both were maybe five feet six. A third said that both were between five feet nine and five feet ten. Yet another said that one was short, the other tall. Three witnesses said that one robber wore white or tan shorts, while three others said both wore bluejeans.

The day after the shooting, police spotted Washington driving the Pathfinder, which had been stolen the previous week. They cornered him in a garage, where they found the gun that had killed Pascall.

That same day, police found Pascall’s Lincoln, stripped and partially burned. The only prints recovered from the car were Washington’s. He told police that, on July 30th, the four men had driven to the Schnucks so that he could buy some dog food. Washington said that Shadwick and Bankhead had robbed Pascall, and that Shadwick had fired the gun.

Three days later, Shadwick turned himself in, accompanied by a lawyer, who advised him not to talk to the police. On August 14th, police arrested Bankhead and Simms. Asked who committed the robbery, Bankhead named Washington and Simms, and said that Washington fired the fatal shot. Simms, on the way to the police station, told two officers that Washington and Shadwick were the robbers, and Washington the shooter. Then, at the station, Simms claimed that Shadwick, Washington, and Bankhead had all got out of the Pathfinder, and that Shadwick shot Pascall.

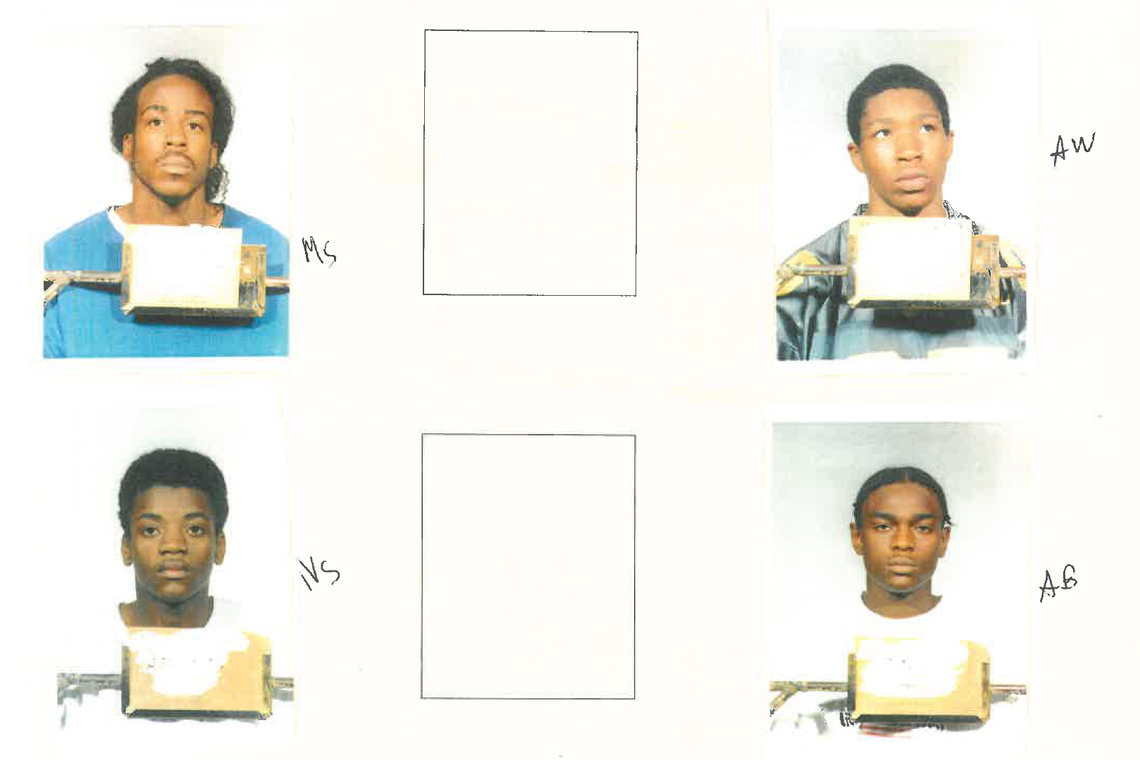

Police created at least four different photo lineups and showed them to eyewitnesses, asking if they could pick out the robbers. Some selected Washington, some Shadwick, some Bankhead. The task was complicated by the fact that Shadwick and Washington were both five-eleven and a hundred and fifty pounds, while Bankhead and Simms were both short and slim. “If you see his picture and my picture, we kind of favor each other,” Bankhead told me. Police settled on Shadwick as the shooter, and Shadwick, Bankhead, and Washington were all charged with murder, robbery, and two counts of armed criminal action.

The task of trying the three went to Robert J. Craddick, an assistant prosecutor with the St. Louis Circuit Attorney’s office. Craddick, who was in his mid-forties, had received his law degree from Washington University, in St. Louis, and had been with the office since 1984; at one point, he had been responsible for training new prosecutors. Police are often critical of prosecutors for being overly cautious, but in St. Louis the police praised Craddick. “He’s the best they’ve got. He’s been an aggressive prosecutor who knows the importance of getting murderers off the street,” one detective later told the St. Louis Post-Dispatch. Craddick told the paper that, during his twenty-one years in the office, he had won all but four of a hundred and sixty-seven cases.

On September 21, 2001, Washington appeared in circuit court with his attorney and pleaded guilty to the four charges.

Craddick, asked to summarize the state’s evidence, said that it would show beyond a reasonable doubt that Washington and Shadwick had “decided to take it upon themselves” to rob Pascall. Shadwick shot him, and the two fled in Pascall’s car.

“Did that happen, Mr. Washington?” the judge asked.

“Yes, sir,” Washington said.

At the hearing, and in others to come, Pascall’s family described their loss. In July, 2000, Pascall’s church had held a two-week revival, where he played the bass guitar. The day he was shot, he had persuaded his father to attend. “He was smiling all day,” his dad said. “We had dinner, he was playing with me. And at the end of that day I didn’t have a son anymore.” Pascall’s wife wrote of seeing his body at the morgue, a tube still in his mouth. She said that, at the funeral, “I just wanted to fall into the casket with him.”

In exchange for Washington’s plea, the state recommended a sentence that would make him eligible for parole in about twenty-two years. The judge accepted the recommendation, but told Washington, “I think I must be getting cranky in my old age. I think you probably deserve to die.”

Nine months later, Martez Shadwick went on trial, before another judge. Craddick, in his opening statement, again said that Shadwick and Washington were the two robbers, and that Shadwick was the gunman. Five prosecution witnesses identified Shadwick as one of the robbers. Craddick didn’t ask the first three witnesses—a nurse, a shoe saleswoman, and a gas-station cashier—about the identity of the second robber. But he did ask the last two: the woman in whose arms Pascall had collapsed, and the woman’s son. Both testified that in a photo array they had picked out Washington.

In closing arguments, Shadwick’s lawyer challenged the reliability of the prosecution’s witnesses. One witness’s description of the robbers didn’t fit Shadwick’s height. Another’s didn’t match his skin tone. The most damning evidence was against Washington: he had been found with the murder weapon, and his fingerprints were the only ones recovered from the Lincoln. “Alvin Washington killed Demetrius Pascall, Your Honor, and Martez Shadwick had nothing to do with it,” the defense lawyer said.

At the trial’s end, on June 20, 2002, the judge complimented both attorneys for “an excellent job of presenting evidence” and found Shadwick guilty of first-degree murder, robbery, and the two other charges.

At Antoine Bankhead’s trial, which began on July 1st, Craddick appeared before a third judge, Joan M. Burger. This time, he changed his lineup of witnesses. The woman and her son, who had identified Washington as Shadwick’s accomplice, weren’t called to testify, but the three witnesses whom Craddick had not asked about the second robber’s identity were called again.

At Shadwick’s trial, the defense attorney had asked two of those witnesses to identify the second robber: the gas-station cashier said it was Washington; the saleswoman said that while looking at police photos she “couldn’t pick that second person out.” Now both said that the second robber was Bankhead. The third witness, the nurse, named him as well.

Bankhead’s attorney later said that he had attended part of Shadwick’s trial, but he did not ask the cashier or the saleswoman about the inconsistencies in their testimony from one trial to the next. Bankhead recalled that, after Washington’s and Shadwick’s convictions, he found the case against him baffling. “I’m, like, hold on, this ain’t right,” he said. “I’m not the smartest man in the world, but this doesn’t make sense.”

In Craddick’s closing argument, he told the jury that there was “no doubt” that Shadwick was the shooter, and that the evidence that Bankhead was the second robber was “uncontradicted.” If Washington had been the second robber, he said, why had no eyewitnesses picked out his photo? Any suggestion that Washington was Shadwick’s accomplice was a “smoke screen.” The jury, after deliberating for less than two hours, convicted Bankhead of all four charges.

When I spoke to Bankhead recently, he gave me his account of Pascall’s murder. He’d been drinking and smoking marijuana that evening, he said, and was asleep in the back seat of the Pathfinder when the sound of the gunshot woke him. He saw that Shadwick was sitting in the front seat. (Shadwick’s lawyer told me that her client was not present. Washington and Simms could not be reached for comment.)

A couple of days after Bankhead’s conviction, while his sentencing was pending, he wrote to Burger, asking for a retrial. “I’m a innocent man,” he said. Only two people had committed the crime, but Bankhead was the third to be convicted. He wrote, “Now don’t you think somethings wrong with that picture your honor.”

Alvin Washington might have helped Shadwick’s and Bankhead’s defenses, and at one point he had promised to do so. In June, 2002, a few days before the start of Shadwick’s trial, Washington wrote to Bankhead’s mother, “i’m sorry for you having to lived these last 2 years without your son and no-dout i feel as if it was my fault because if i wouldn’t have said nothing he wouldnt be in this situation … i was thinking selfish at that time … getting them before they got me.” He said that he would help Bankhead and Shadwick when their trials came, “cause theirs no reason for everybody to go down for one dead body.” He even signed an affidavit, saying that Bankhead and Shadwick played “no active part” in the crime.

Shadwick’s lawyer arranged for Washington to testify at Shadwick’s trial, and had him transported from prison. But at the courthouse Washington balked. Bankhead’s lawyer wanted a jail officer to testify that she had overheard Washington tell other inmates that he was the shooter, and that Shadwick and Bankhead had stayed behind in the S.U.V. But the judge prohibited the account as hearsay.

On July 26, 2002, the sheriff’s department carried Shadwick into court for sentencing, restrained with a belly chain and leg irons. “You convicted me for something I didn’t do, man,” Shadwick said as the hearing started. “Why you doing this, man? God, I don’t know why you’re doing this—”

“Mr. Shadwick, please,” the judge said.

Shadwick kept saying that he was innocent: “I didn’t do it, man…. God know I didn’t do it…. I know you think in your head, oh yeah, I got gold, I got braids, I’m black, I’m a teen-ager, but that ain’t me, man…. I’m not no robber, I’m not no murderer.” Shadwick said, “Craddick know that I’m innocent. He know. He just wants a conviction, man.” He claimed that Bankhead was innocent, too, and all but named Washington and Simms: “The dude that done it may be sitting in the penitentiary right now, laughing at me, and the other dude did it, man, and he didn’t even get convicted, man.”

On Craddick’s recommendation, the judge sentenced Shadwick to life without parole.

“Why? Why life without? Why?” Shadwick said.

“Mr. Shadwick, please,” the judge said.

The following month, Bankhead returned to court to be sentenced by Joan Burger. “I thought it was a just trial,” Burger said, in court. She knew that two other men had been convicted in the case, but she wasn’t aware of the particulars: a judge is supposed to see only the evidence presented in her court. Burger sentenced Bankhead to life with the possibility of parole.

In late 2003, Bankhead asked to have his conviction thrown out based on the prosecution’s conflicting theories and his trial attorney’s failure to capitalize on the inconsistencies. The motion went before Burger, and, for the first time, she was presented with transcripts from Washington’s plea hearing and Shadwick’s trial.

Burger told me that when she read the two court files she was shocked by the contradictions. Burger had been a circuit-court judge for thirteen years and, before that, an attorney in the same office as Craddick. As a prosecutor, she said, “you have a duty to justice, for both the victim and the defendant, and we took that to heart.” Craddick had often appeared in Burger’s court, and she considered him a good, experienced prosecutor. “He was very serious. There was no lightheartedness in him,” she said. “He didn’t think he did anything wrong. But, wow.”

Burger held a hearing on Bankhead’s motion in March, 2004. Arthur Allen, an assistant public defender, represented Bankhead, who had turned twenty-two the week before. “He just struck me as a kid,” Allen told me, adding that Bankhead was small and “extremely quiet.” Going into the hearing, Allen didn’t give much of a chance to his argument about conflicting theories. “It seemed to be something that prosecutors got away with,” he said. But that changed when Burger summoned the lawyers to the bench. “She was angry. You could tell that,” Allen said.

Craddick wrote that the state “did not use inherently factually contradictory theories.” It had accused the three defendants of “acting with each other.” Burger was unmoved. Two months after the hearing, she threw out Bankhead’s conviction, writing, “The state has convicted three people for the acts of two.”

There is no simple explanation for why a prosecutor might argue contradictory theories. In a 2012 law-review article on inconsistent prosecutions, Brandon Buskey, now a senior staff attorney with the A.C.L.U. Criminal Law Reform Project, identified “three basic types” of prosecutor in these cases: the “win at all costs” prosecutor, obsessed with conviction rates; the “agnostic” prosecutor, who feels no need to be convinced of a defendant’s guilt and defers “responsibility for protecting innocence to the trial judge, defense counsel, and the jury”; and the “genuinely uncertain” prosecutor, who doesn’t know which defendant did what, and is fine with leaving it to a judge or a jury to decide.

On rare occasions, attorneys for a defendant get a chance to ask prosecutors under oath about their thinking. That happened in one case with conflicting prosecutions in California. In 1982, Samuel Bonner and Watson Allison robbed an apartment in Long Beach. One resident, twenty-three-year-old Leonard Wesley Polk, was shot twice in the head and killed. Kurt Seifert, of the Los Angeles County District Attorney’s office, prosecuted both men.

At Bonner’s trial, in November, 1983, Seifert , pursuing the death penalty, argued that Bonner and Allison went into the apartment, and Bonner fired the two shots. The jury convicted Bonner of murder and robbery but concluded that he wasn’t the shooter, and Bonner received a life sentence. Two months later, at Allison’s trial, Seifert again pursued the death penalty. This time, he argued that Allison went into the apartment alone, and that he fired the shots. Bonner, Seifert now argued, was only a “wheelman,” who drove Allison to and from the crime. Allison was convicted and sentenced to death.

In 2008, Allison’s attorneys questioned Seifert as part of Allison’s federal habeas-corpus petition. Seifert, now retired, had been a prosecutor for thirty-two years, and said he believed that “the role of the prosecutor is not to win. The role of the prosecutor is to represent the parties that he represents with an eye to doing the right thing. And the right thing means, right or wrong, present the truth. And if the truth stacks up against your position do not prosecute.”

Seifert went on, “Truth is not a block of stone. It is a malleable gray area. There can be nuggets of truth, bits of lies. It’s all—it’s a fluid idea, even. What’s true one day may not be true another. Pluto is no longer a planet.”

Martin Sabelli, one of Allison’s lawyers, recalled that Seifert seemed indifferent to the importance of the case: “He had a smile that leaned more toward sarcasm than irony.”

“In the Bonner trial, you had argued that Mr. Bonner had been in Mr. Polk’s apartment?” Sabelli asked Seifert.

“Absolutely.”

“And in the Allison trial you argued that Mr. Bonner had never been in Mr. Polk’s apartment.”

“Well, huh. That was a booboo. You can quote me.”

When Seifert was asked about arguing in the first trial that Bonner was the triggerman, then in the second trial that Allison was the triggerman, he referred to that switch as “the big oops.”

Seifert didn’t say those words with any sense of embarrassment, Sabelli told me. “It was more, like, boastful, it was more a ‘What are you going to do about it?’ kind of tone.” Michael Clough, another of Allison’s lawyers, said he believed that Seifert wasn’t being flippant. His words were an “honest, direct reaction” to realizing what he’d done. (At another point, Seifert, reviewing the contradictions in his arguments, said, “Whoa.”)

A minute or two later, Seifert said, “There was only one issue ever in the case, and that is triggerman. And, frankly, I don’t know who pulled it. Today, if you asked me who pulled the trigger, I don’t know.”

“At the time, you didn’t know, either?” Sabelli asked.

“I would have to say that’s true based on the way things panned out,” Seifert said. (He could not be reached for comment.)

In 2010, a district-court judge ruled that Seifert’s first theory—that both Bonner and Allison entered the apartment—was more likely true than his second, and threw out Allison’s death sentence. Allison is now serving twenty-five years to life at the California State Prison in Solano. Bonner is at the California Men’s Colony, in San Luis Obispo.

In the Missouri case, Bankhead remained in prison while prosecutors appealed Burger’s ruling. The case came up for oral argument in August, 2005, before the Missouri Court of Appeals. The three judges—all former prosecutors—left little doubt that they believed the state’s theories to be irreconcilable. “This has a smell-test problem,” one of them said.

The following month, the St. Louis Post-Dispatch reported that Craddick was leaving the Circuit Attorney’s office to practice civil law. Craddick said that he had four children and couldn’t afford “several college tuitions on a government salary.” “His leaving is a great loss,” one police detective told the newspaper. Another said, “He’s the only guy over there who would take a chance on a case. It didn’t have to be a slam-dunk winner for him to take it.”

In January, 2006, the Court of Appeals unanimously upheld Burger’s ruling. Bankhead was released from state custody later that year. Shadwick also appealed his conviction, but lost. Both Shadwick and Washington remain in prison. Bankhead, who later spent another five years in prison, for unrelated crimes, works at a packaging warehouse in southern Illinois.

Craddick now serves as in-house counsel for a health-care company. When I asked him about Bankhead’s trial, he recalled that the jury’s deliberations had been short—“one hour and thirty-three minutes”—but said he hadn’t heard that the conviction had been overturned. I explained that Burger and the Court of Appeals had found that he had violated Bankhead’s due-process rights. Craddick said, “Hmm. I don’t have any real comment about that, because it was so long ago.” He added, “I prided myself on being a prosecutor who played by the rules,” but otherwise declined to talk about his time in the Circuit Attorney’s office. “It doesn’t do any good to talk about something so long ago,” he said.

This past August, I called one of the jurors from Bankhead’s trial, Susan Conway-Wiesen, who described herself as “a little old lady with gray hair.” She had no idea that, two weeks before that trial, the prosecutor had argued that the second robber wasn’t Bankhead but Washington. When I told her, she gasped.

“That is terrible. That is just terrible. I think our justice system should actually be”—she paused—“justice. I think that is awful.” Later, she began to cry. “My goodness, I really need to think about this one.”

She said that the deliberations were short and straightforward. “Based on what we were told, it was hard to come up with a different conclusion.”

I asked if it would have made a difference to know that the prosecutor had earlier accused someone else. “Absolutely,” Conway-Wiesen said. “Oh my gosh, that’s outrageous.”

More than thirty-three years after John Stumpf and Clyde Wesley appeared at the Stouts’ door, the debate over Stumpf’s fate will soon be renewed. In 2011, six years after the Supreme Court declined to rule on whether the conflicting prosecutions should invalidate Stumpf’s death sentence, the Sixth Circuit Court finally ruled on the question. A three-judge panel vacated the sentence. Two years later, the court agreed to rehear the case with all judges sitting, and reinstated Stumpf’s death sentence. The vote was 9–8.

Last month, I spoke on the phone to Norman Stout, who is eighty-seven and still lives in Guernsey County. I asked him if he wanted to attend Stumpf’s execution. “Absolutely,” he said. “I offered to pull the lever.” For Stout, the use of contradictory stories was unimportant—the man who didn’t fire the gun did nothing to stop his wife’s murder. He recalled that Mary Jane sang Patsy Cline tunes on a weekly radio show, and wore her hair the way Cline did. After his wife’s death, Stout continued to add to her collection of Holly Hobbie memorabilia, eventually opening a gallery where he displays more than twelve hundred items. He thinks about her constantly, he said.

Stumpf is scheduled to be executed in the spring of 2020. In 2005, during oral arguments in Stumpf’s appeal, Justice Scalia suggested the clemency stage as the time to argue the right and wrong of alternative theories. Let the governor “figure out which one of the two wasn’t the shooter,” he said. That’s an invitation Stumpf’s attorney, David Stebbins, will likely accept, when it comes time to ask Ohio’s governor for mercy. In clemency, the issues can be esoteric. But that’s not true in this case. Stebbins said, “This is one issue that I think everyone can understand.”

We've identified more than four dozen cases in which a defense attorney argued in an appeal that the prosecution had told conflicting stories about the crime. Here are nine of them.

Lynn, Massachusetts

Cristian Vargas-Martinez was killed with a single gunshot outside a restaurant. Two men stood trial — Bonrad Sok, then Kevin Keo. At Bonrad Sok’s trial, in May of 2009, the prosecutor argued: “Kevin brought the gun and Bonrad shot it.” Six months later, when Kevin Keo stood trial, the same prosecutor argued that Sok had been too far away to fire the shot. The actual triggerman, the prosecutor said, was Keo: “Who else is out there? Him [Keo], right there. He came around the side and shot him.” Both men were convicted of murder. The Supreme Judicial Court of Massachusetts affirmed Keo’s conviction in 2014, saying the prosecution’s about-face did not violate due process.

Stuart, Florida

Frances Slater, a convenience store clerk, was kidnapped and shot to death in 1982. Three men stood trial, separately. At John Earl Bush’s trial, the prosecution argued Bush was the shooter; at Alphonso Cave’s trial, that Cave was the shooter; at J.B. Parker’s trial, that Parker was the shooter. All three men were sentenced to death. A federal appeals court found nothing wrong with this, saying the evidence was uncertain, so it was okay for prosecutors to argue alternate theories. Bush was executed in 1996.

Torrance, California

Willie Yen was killed with a single bullet in 1995. On back-to-back days, two men stood trial. “The evidence is manifest,” the prosecutor said the first day. “It’s unrefuted that John Winkelman is the actual killer.” The next day, before a different jury, the same prosecutor said that the evidence was “100 percent consistent with Stephen Davis firing that fatal round.” Winkelman and Davis were both convicted of murder and sentenced to life. The prosecutor told the Los Angeles Times that the two juries heard from different witnesses, and he simply argued “logical inferences that can be drawn from the evidence.” “Legally, I’m on solid ground,” he said. A Torrance Superior Court judge agreed, refusing to throw out Winkelman’s conviction.

New Haven, Connecticut

Gunfire from a passing car killed one man and wounded another. Three men were in the car. Forensic evidence indicated only two guns were used. At Thomas Rogers’ trial, the prosecution argued Rogers was a shooter; at Isaac Council’s trial, that Council was a shooter; and at Larry McCown’s trial, that McCown was a shooter. Council claimed the illogical result — two guns, three shooters — violated due process. In 2009, an appeals court disagreed, saying that while the state varied its arguments, the evidence it presented in each trial was the same.

Newark, New Jersey

Two people were murdered during a gas station robbery in 1991. Four men stood trial. At three of the four trials — for Billy Jackson, Lawrence Wright, and Kevin Oglesby — the prosecutor argued that the two shooters were Jackson and Wright. At the fourth trial, for Winston Roach, the same prosecutor argued that the shooters were Jackson and Roach. The state “contends that the evidence permits two factual scenarios,” wrote the New Jersey Supreme Court — which was fine with that. “The prosecutor properly presented different, plausible interpretations of the conflicting evidence,” the court wrote.

Houston, Texas

In 1980, two men robbed a delicatessen. In the holdup, an employee, Claude Shaffer Jr., was killed with a single shot. At Willie Ray Williams’ trial, the prosecutor argued: “Willie Williams is the individual who killed Claude Shaffer. That’s all there is to it. It is scientific. It is complete. It is final and it is evidence.” Later, at Joseph Bennard Nichols’ trial, a different prosecutor from the same office argued: “Willie could not have shot him. And I submit to you from this evidence [Nichols] fired the fatal bullet.” Nichols also received a death sentence. A federal judge threw out Nichols’ conviction, writing: “Williams and Nichols cannot both be guilty of firing the same bullet because physics will not permit it.” But that judge’s ruling was subsequently overturned. Both men were executed — Williams in 1995, Nichols in 2007.

Oklahoma City, Oklahoma

Two men robbed a Root-N-Scoot convenience store in 1992. The store’s owner was shot and killed. At Glenn Bethany’s trial, the prosecutor argued Bethany was the triggerman, citing eyewitness testimony that the taller of the two robbers opened fire. At Emmanuel Littlejohn’s trial, the same prosecutor argued the shooter was Littlejohn, citing a witness who saw Littlejohn pointing his gun (but did not see it fire). “[G]iven the uncertainty of the evidence it was proper for the prosecutor to argue alternate theories as to the facts of the murder,” an appeals court wrote.

Cape Girardeau, Missouri

In 1987, in a fight outside Corky’s Lounge, William Fondren cut John Lupo’s face with a knife, the wound requiring thirty-five stitches. At Lupo’s trial, the prosecution said Lupo was the aggressor. He was convicted of disturbing the peace. Six months later, the prosecution said the aggressor was Fondren, with Lupo now “the victim.” Fondren was convicted of assault and sentenced to six years. In 1991 the Missouri Court of Appeals affirmed Fondren’s conviction, saying Fondren wasn’t a party to the first case — that is, the criminal proceedings against Lupo — so any position the state took in the first proceeding did not restrict its position in the second.

Minter City, Mississippi

A deputy sheriff transported three prisoners from a county jail to the state penitentiary in Parchman, Mississippi. On the way, near Minter City, the prisoners escaped and the deputy was killed, shot three times with his service revolver. When Stephen A. Sutherland stood trial in 1986, the prosecution argued Sutherland fired all three shots. Four months later, at the trial for Marvin Edward Hoover, the prosecution argued Hoover fired every shot. Both men were convicted of capital murder. At the second trial, Hoover wanted the jury to know what the prosecutor had argued in the first trial — but the judge disallowed it. The Supreme Court of Mississippi ruled that the judge fouled up, but affirmed Hoover’s conviction anyway, concluding the error was harmless.