On a humid day in April 2009, the sound of gunfire drew police to a suburban home in Jefferson Parish, La. Officers found no shooters or victims — just an empty backyard littered with shell casings. In an area with the nation's highest gun death rate, the incident seemed pretty minor. "Garden-variety case," is how one detective described it.

Still, the casings were taken to the crime lab and entered into a huge federal database run by the Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms and Explosives.

The next morning, just blocks away, men broke into an apartment intending to rob a drug dealer. Instead, they killed a toddler, his 19-year-old mother and a 6-year-old boy. An 11-year-old girl was wounded, and her two friends survived by playing dead. Scattered amid the carnage were eight shell casings. Those went into the database, too.

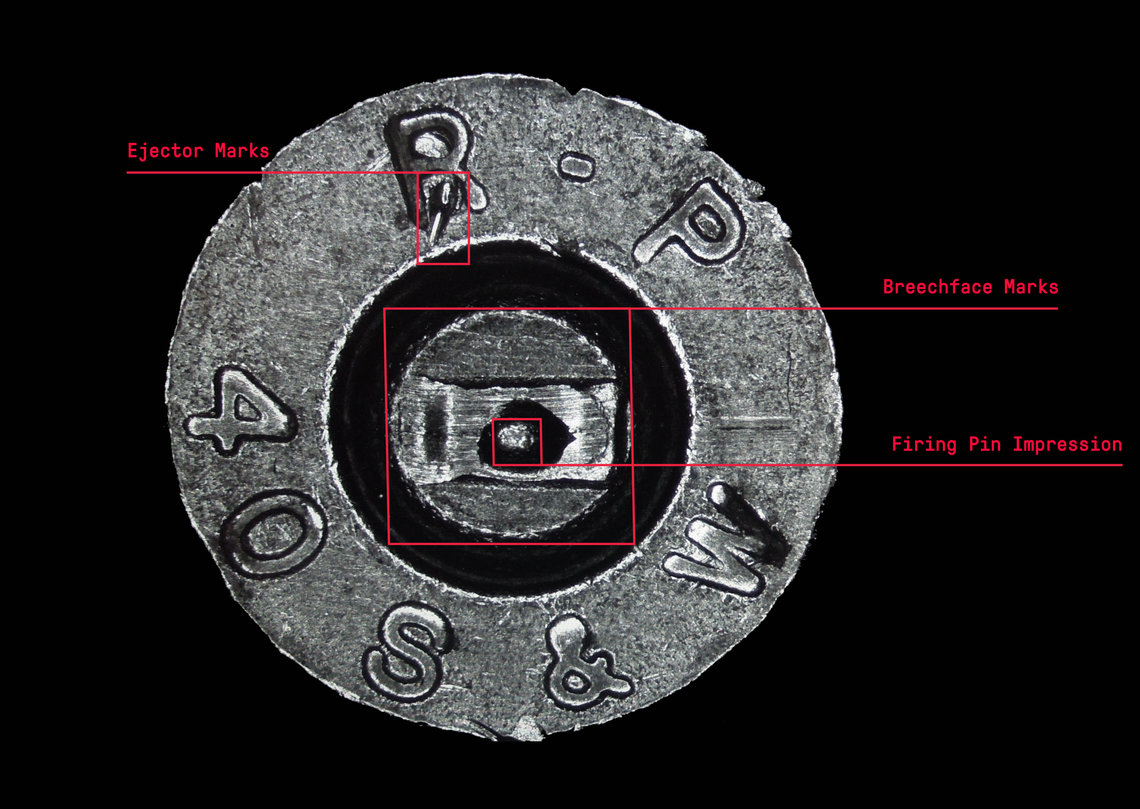

The database, called the National Integrated Ballistic Information Network (NIBIN), contains high-resolution images of almost 3 million casings police have collected from crime scenes or test-fired from guns used in crimes nationwide since 1999. The software reads unique markings that guns leave on shell casings and then flags potential matches, signaling when the same gun may have been used in more than one shooting.

NIBIN revealed links between four guns used in the Jefferson Parish triple homicide, the backyard incident and five other shootings. The evidence led investigators to a witness who helped convict their main suspect in the triple homicide, one of dozens of highly publicized cases solved nationwide with the technology's help. In cases such as this, NIBIN has been an invaluable tool for police, linking seemingly unconnected crimes and helping to catch criminals who might otherwise go free.

But ATF's ambitions for NIBIN far outstrip its accomplishments.

Since the program began two decades ago, more than $300 million has been invested in it. Yet only a few hundred of the nation's 18,000 police departments use the database. Eleven states have no NIBIN terminal, where images of the casings are loaded into the database and matched. An additional 19 states, plus Washington, D.C., have only one or two terminals.

Even among departments that use the system, only a handful have been using it the way ATF intends. NIBIN has been hobbled by years of inattention inside ATF, according to more than two dozen current and former NIBIN officials and law enforcement agents, some of whom spoke on the condition of anonymity because they were not authorized to talk about it. Because the technology requires a considerable commitment of personnel and money, many departments have adopted it in a scattershot way: they enter shell casings inconsistently and fail to follow up on leads.

John Risenhoover, the former NIBIN national coordinator for ATF, retired last year after 26 years at the agency, in part, he said, because the agency's commitment to the program has been inconsistent. "If you initiate it and operate it in a real-time manner, it's phenomenal," he said. "But NIBIN to this point was a huge waste of cash."

The Police Executive Research Forum (PERF), an influential Washington policing think tank, is studying NIBIN programs in Denver, Milwaukee and Chicago, among the most widely lauded. The research — the first of its kind in the program's lifespan — was intended to show other departments how to set up successful NIBIN operations. But the findings have been far from clear. "Most departments, including those we are working with, have not comprehensively implemented the model," PERF told the Marshall Project in a statement.

The problems date back years. A 2005 audit by the Justice Department's inspector general found that few law enforcement agencies participated in the program, and those that did had a "significant backlog of evidence that had not been entered into NIBIN, primarily because of staffing shortages and other priorities."

Now, as ATF is in the third year of a new push to persuade local law enforcement agencies to embrace a NIBIN-centered gun crime strategy, the program is at a crossroads. Spending is set to grow to $36 million in fiscal year 2017 from $13 million in 2013. The bureau recently opened a national command center where departments can outsource one of the more time-consuming aspects of NIBIN to get more cities on board. And ATF has begun aggressively promoting the database as a powerful tool that can prevent gun crime by identifying the small number of people behind a disproportionate number of shootings.

James Ferguson, chief of the Firearms Operations Division at ATF, acknowledged in an interview that few police departments nationwide are using NIBIN the way the agency intends. But he said that ATF's new approach will lead departments to fully embrace NIBIN once they see the potential for long-term benefits.

Meanwhile, "is it more beneficial for them to do it halfheartedly versus not at all? I would argue that it is," Ferguson said. "If they are getting some leads out of the system, is that better than no leads?"

For NIBIN to work as a preventive strategy, police must investigate shots fired at stop signs as aggressively as they chase killers, said current and former top ATF officials. "My goal isn't to solve a murder," Risenhoover said, "but to catch these guys before they commit a murder."

In Denver last year, for example, police responded to an alert from ShotSpotter — a system of sensors that alert police to the sound of gunfire — to find shell casings on an empty sidewalk. Entered into NIBIN, those casings revealed a link between two shootings committed earlier that week. In one, a burglar shot at a woman who confronted him as he broke into her home. In the other, someone shot a family's dog during a break-in.

Witness descriptions from the ShotSpotter call led police to a man who ultimately pleaded guilty to charges related to all three incidents. If police had not quickly entered the casings from the seemingly low-priority shooting, the shooter would have continued his crime spree and "actually killed somebody," Jeffrey Russell, program manager of ATF's NIBIN branch, told law enforcement agents in a webinar in May.

The ATF calls this approach to gathering gunshot evidence "comprehensive collection," and the agency says it is critical for NIBIN's success. "If you're picking and choosing what you're putting into NIBIN, you're not getting a clear picture and you're going to limit your effectiveness," Russell said.

Another critical step is timely turnaround: getting the casings into the system, and the leads back out again, within 24 to 48 hours.

In the past several years, ATF has been pushing local law enforcement to adopt this new wraparound approach to gun crime through local "Crime Gun Intelligence Centers."

Denver police, with help from ATF, opened the first center in 2013, and similar programs followed in Phoenix, Chicago, New Orleans, Milwaukee and elsewhere.

But police departments using NIBIN rarely treat every shooting as a potential homicide.

Comprehensive collection and timely turnaround requires buy-in from everyone involved. Multiple sources from inside ATF and law enforcement around the country said that few departments have even come close. Police officials in Denver and Chicago declined to be interviewed. In at least a dozen cities, officials said one of the main obstacles to using NIBIN as ATF envisions is manpower.

"We have way too much gun violence, and there's only so many police officers," said Milwaukee police Capt. David Salazar, who oversees that city's crime gun intelligence efforts.

The impact of NIBIN on violent crime over the past two decades is unclear: ATF does not formally track it.

The primary NIBIN metric that ATF makes publicly available is the 75,000 "hits" — or confirmed matches — the system has generated nationwide since it began. The bureau does not track how many hits end in arrests or convictions or whether the number of shootings or violent crime rates have gone down in places that use NIBIN.

The theory underlying NIBIN — that every gun leaves its own fingerprint — has never been scientifically proven. The National Institute of Standards and Technology has a long-term research project underway to answer that question. But most experts think the basis for NIBIN is sound, a belief borne out by the tens of thousands of confirmed matches the system has identified over the years.

Before NIBIN, firearms examiners looked for matches by tacking Polaroids of casings to the wall, grouped by caliber, and comparing them when new photos arrived. NIBIN's predecessor programs — Drugfire compared casings at the FBI, Ceasefire compared bullets at ATF — automated the process and linked it with other departments.

Today, NIBIN searches millions of high-resolution 2-D and 3-D images from machines in multiple states for comparison. It takes about 10 minutes for a technician to enter a casing into the system. Several hours later, the computer spits out a list of up to 200 potential matches.

A technician then reviews each image to look for more exact matches. This year ATF opened a centralized clearinghouse where departments can outsource this step. It takes about 15 minutes.

Until recently, once NIBIN identified a potential hit, a firearms examiner had to confirm the match by comparing the original casings under a microscope. If the original casing was in another city or state, someone had to drive or fly to pick it up and bring it back to be compared and then peer-reviewed — a labor-intensive process that could take months.

This made the technology essentially useless in solving typical gun crimes, where trails go cold in a matter of days. For years, police departments tended to use the system only for homicides, cold cases and other rare high-profile crimes. The problem created a catch-22: NIBIN needs police to regularly enter casings to be effective, but police did not want to use it because they did not see the payoff.

In 2011, ATF began slashing the program's budget and pulling machines from sites not generating enough hits. The program went from a high of about 230 sites in 2005 to a low of about 140 in 2012. As of last month, there were 161 sites.

This number is not likely to change much in the future: Each machine costs upwards of $150,000, including maintenance and other costs. Although ATF used to fund the machines, local law enforcement now has to pick up the cost.

John DeVito, deputy chief of firearms at ATF, said in an interview that the agency's money is better spent providing education and support to the cities that already have NIBIN machines. "We want to first ensure that the machines that are out there are being used in the most efficient way possible," DeVito said.

In 2013, a National Institute of Justice report concluded the system was hobbled by "chronic underfunding and a limited vision of its true capacity." The researchers noted that by focusing too much on NIBIN as a tool to solve individual crimes, ATF missed the chance to prevent new ones.

The report jolted ATF, which decided to experiment with a new way of using NIBIN, several officials said. Instead of waiting for a firearms examiner to confirm a match, the system would push out potential leads to investigators while they were still hot.

"A 10-month-old NIBIN hit is no good to anybody," says Lt. Jack Donegan of the New Jersey State Police, which recently streamlined its processes to slash wait times on NIBIN leads. "A 24-hour NIBIN hit means the world to the detectives that are out on the street."

Even Milwaukee, which has made a big commitment to the Crime Gun Intelligence Center it launched in 2014, struggles to meet ATF's NIBIN benchmarks. As part of its new comprehensive gun crime strategy, Milwaukee began using ShotSpotter, revealing that residents in some high-crime neighborhoods were so used to the sound of gunfire or so wary of police that they rarely called 911 when shots were fired.

To follow ATF's new tenets, police had to respond to many more incidents, and collect and input hundreds of additional casings into NIBIN. Even with a combined force of five police employees and ATF agents, it can take several days, or longer, for casings to be entered and potential hits to go out.

In the majority of sites, the NIBIN machine is still located in the crime lab, where firearms examiners — at times, reluctant to cede control over what has long been their turf — resist sending out unconfirmed leads, according to ATF and law enforcement officials in cities that have tried to implement the crime gun intelligence model. "The biggest roadblocks at the beginning were cultural, and were primarily with the prosecutors' office and the crime lab," Milwaukee Police Chief Ed Flynn said.

In Washington, D.C., the Metropolitan Police Department works closely with ATF's new regional crime gun intelligence center in Greenbelt, Md. District police Cmdr. Robert Alder says NIBIN is "invaluable" to police in solving crimes and identifying hotspots in conflict areas. But limited resources force them to prioritize: not every shooting gets assigned a detective, and not every lead is run down, according to Alder and Christie Weidner, ATF's Crime Gun Intelligence group supervisor.

"If you tried to vet 100 percent of the information, the line detectives and the line agents will be overwhelmed. They will get discouraged," said Rich Marianos, who retired as assistant director of ATF's Washington field division in 2014.

Other cities have not made the same level of commitment to NIBIN.

The Los Angeles Police Department — which was a NIBIN trailblazer in some ways, pushing out unconfirmed leads as early as 2003 — requires the detective on a case to personally bring shell casings to the lab, said Doreen Hudson, the commanding officer at the department's forensics division. This often means only the high-priority crimes get entered quickly, if they are entered at all. Other officials at the department declined to comment on why the agency does not use NIBIN more widely.

In San Antonio, ATF pulled the police department’s NIBIN machine because the city was not using it enough, despite having a firearm death rate on par with Washington, D.C. One county official there said he did not think comprehensive collection was a worthwhile goal. “There are just so many guns out there. That attitude is, ‘Wouldn’t it really be important to look through every haystack just because there’s a needle in there?’ ”

Whether using NIBIN feels worth the effort depends, in part, on how many leads it generates. In Milwaukee last year, 38 percent of entries resulted in a potential lead, according to data provided by ATF. Milwaukee's rate was the nation's highest. The average rate nationwide last year was 10 percent, and it was in single digits the previous four years, ATF data shows. In New Jersey, it's 14 percent. "Most of our guns that we process, turns out, we don't need to even process them," says Maj. Geoffrey Noble with the State Police. "But we don't know that until we do it."

But most departments using NIBIN have trouble keeping up with the leads.

In Chicago, where police take more than 6,500 guns off the street each year — more than one for every two-hour period — 36 ATF agents and Chicago police detectives are dedicated solely to following up NIBIN leads. Is that enough to run down every lead? "Absolutely not. There's too many," says Jim Needles, who recently retired from the ATF's Chicago field division.

Instead, the team identifies which leads provide the most readily actionable information, and which are associated with the most serious crimes.

Even in a small city like Portland, Ore., detectives can’t keep up. Lt. Mike Krantz, who heads that city’s NIBIN program, said they received 76 leads in the first four months. “It’s a little bit overwhelming number of leads for us to follow up on,” he says. The team reviews leads at roll call each morning and identifies the high-priority ones to pursue.

That approach frustrates those who see the potential of NIBIN.

"If you don't address these kids who shoot up a house, you see an escalation of violence," Risenhoover said. "How many shootings have you committed before your aim was accurate enough to kill somebody?"