It’s not yet publicly known if Officer Jeronimo Yanez ran the plates of the Oldsmobile Aurora that Philando Castile was driving before pulling him over in Falcon Heights, Minn., the night of July 6.

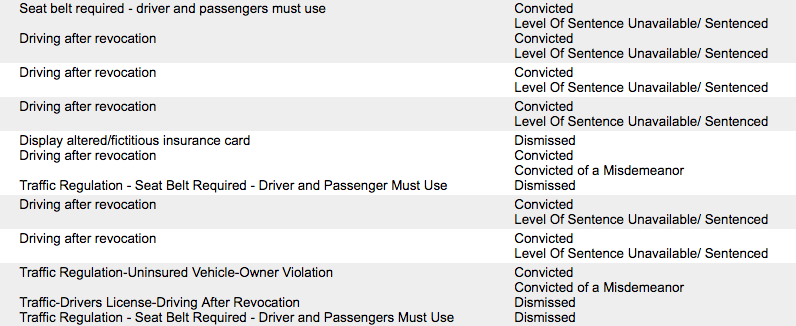

If he did — assuming Castile owned the car, also still unconfirmed — the computer in Yanez’s cruiser would have lit up like a Christmas tree. With at least 52 charges and 35 convictions over 14 years, Castile would seem to have the record of a career criminal.

Yet look closer and there’s no evidence of that. Minnesota courts list serious crime and driving records together, and Castile’s show no citations for criminal behavior beyond motor vehicle infractions and a dismissed marijuana charge.

In the heat of the moment of a police stop, that distinction could be lost on an officer scanning the record while maneuvering his quarry to a stop, says one prosecutor.

“If an officer has a report like that, it could cause an extra rush of adrenalin,” said Mark Rubin, the county attorney for Minnesota’s St. Louis County, about 130 miles north of the Twin Cities. “And there could be consequences.”

Rubin is not involved in the case. His personal reaction was “Wow!” when told of the extent of Castile’s file — before learning that none of it involved serious crime.

And virtually no safety violations, either. Castile, 32, had no drunk driving, hit-and-run or reckless driving charges. Except for two speeding tickets and a cryptic charge of “Public Nuisance-Interfere/Obstruct/Render Dangerous Public Road/Water,” none involved safety — save to himself, with three citations for failing to wear a seat belt. His most recent charge, in January, was a parking ticket for “abandon [ing a] motor vehicle on any public/private property without consent,” for which he was fined $36.

Mostly, the St. Paul public schools cafeteria supervisor was dogged by repeated charges of “no proof of insurance,” going back to 2002 when he still had his learner’s permit, and driving after suspension and, later, revocation of his license.

Fred Friedman, the retired chief public defender for Northeast Minnesota, called it unusual to be stopped so many times with no serious charges.

“It’s a big deal to get stopped 52 times. You can’t find somebody who’s been stopped 52 times and doesn’t have any felony convictions or drunk driving. That’s highly unusual,” he said.

“Why was his license revoked? Was it just this insurance nonsense?” he continued, noting there’s little chance that officers would know of Castile’s troubles with the Department of Motor Vehicles just by seeing him driving along. “Here’s the heart of it: Why did he keep getting stopped?”

Diamond Reynolds, Castile’s girlfriend, who live-streamed the harrowing events moments after the shooting as Castile lay dying in the driver’s seat next to her, said they were pulled over for a broken taillight. With an officer’s gun still trained on her, Reynolds also said Castile told the officer he had a concealed carry permit.

Yanez’s lawyer responded to the Associated Press that the St. Anthony, Minn., officer shot Castile not because Castile was black but because he saw a gun.

A report from KARE-TV presented unconfirmed audio purportedly from Yanez’s squad car before the shooting. In it, officers can be heard saying that Castile resembles a man who robbed a nearby gas station on July 2 because of his “wide set nose” — a remark Castile’s family has branded as racial profiling.

“I’m going to stop a car,” one of the officers says on the recording. “I’m going to check IDs. I have reason to pull it over.”

How valid that reason was is yet to be revealed, and may be answered following the investigation.

But why Castile was pulled over so frequently before that may never be explained — except perhaps by the accident of his birth, as a black male.

Robin Washington writes frequently about transportation and civil rights and is the former editor of Minnesota’s Duluth News Tribune. He may be reached at robin@robinwashington.com or via Twitter @robinbirk.