Texas and Georgia each have an execution scheduled for the night of July 14. If either occurs, it will mark the end of one of the longest stretches the U.S. has gone without executing someone in more than two decades.

The last person put to death was Earl Forrest, a man convicted of killing three people, including a sheriff’s deputy, in a shootout that began as a drunken argument over a methamphetamine deal and a lawn mower. Missouri executed him on May 11.

If Texas or Georgia go ahead with their plans, it will have been 64 days between executions. Over the past 24 years, only once have we gone more than two months without an execution in America. That record is held by a seven-month halt nearly a decade ago when the Supreme Court was deciding whether the prevailing method of lethal injection was constitutional.

In September 2007, the Supreme Court agreed to hear Baze v. Rees, in which condemned men in Kentucky challenged the state’s lethal injection process, arguing it violated the Eighth Amendment’s protection from cruel and unusual punishment.

All executions across the country stopped while the Court considered the case. More than six months later, the Supreme Court upheld the constitutionality of lethal injection. Almost three weeks after the Court’s decision, Georgia put to death William Lynd, and the death penalty went back into full swing, never halting for more than 50 days at a time. Until now.

Looking back, the modern era of capital punishment was inaugurated by a different Supreme Court case. In the Gregg v. Georgia decision, issued on July 2, 1976, the Court found that the death penalty, if applied correctly in the most serious cases, does not violate the Bill of Rights. The Marshall Project’s namesake, Justice Thurgood Marshall, wrote one of two dissenting opinions in the case.

The new execution age got off to a slow start. Six months after the Court’s Gregg decision, a Utah firing squad executed Gary Gilmore.

After that, it took another two years and four months — 858 days — until the second execution of the modern era took place in Florida. For much of the next decade and a half, the death penalty lurched forward in fits and starts. Between 1979 and 1983, the average time between executions was 189 days, more than six months.

By the mid-1990s, however, things were chugging along: 1999 saw 98 executions, the most in a single year in the modern age, occurring roughly every 3.7 days. Things have slowed since then. Thus far this year, executions have been carried out approximately every two weeks.

What’s causing the slowdown? Prosecutors are seeking the death penalty less often, in part because it’s become a more expensive case to prosecute and win. And even for those already convicted and who have exhausted their appeals, fewer states are able to carry out executions. Some states are wrapped up in court, fighting litigation from Death Row prisoners. Some states have also acknowledged that they can’t legally obtain lethal injection drugs or the supply they have is expiring.

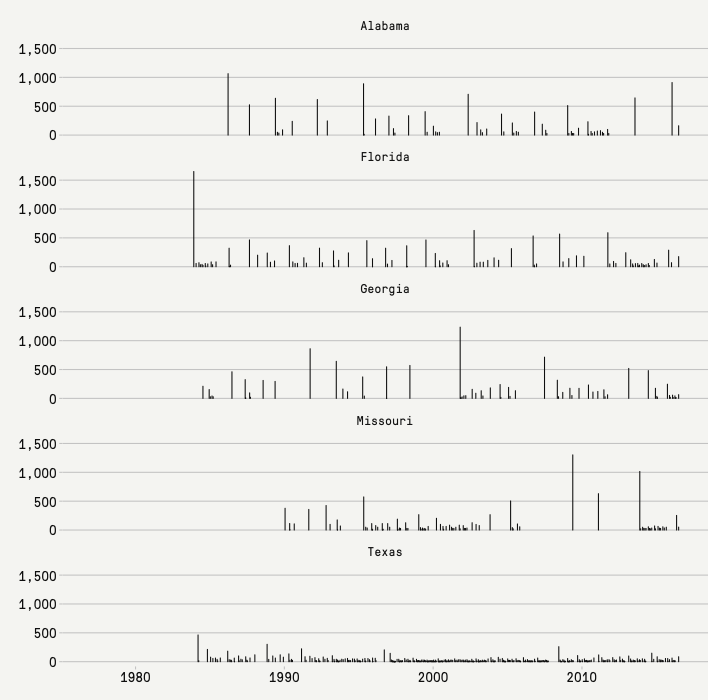

While most states can’t (or aren’t) carrying out executions, when you look at the states that have executed people this year, you see a few clear patterns. In places like Alabama and Florida, there are routinely gaps over the decades. In Missouri and Georgia, there are more irregular gaps, with some lasting three years. And then there’s Texas, which has executed more people than the next six states combined and leads the nation again this year. The most recent two executions scheduled in Texas were halted by stays by the state’s Court of Criminal Appeals as part of the appeals process.

Does this recent lull foretell the end of the death penalty? As long as Texas continues — and it has six more executions on the calendar after July 14 — probably not. At the halfway point of the year, the U.S. is on pace to have as many executions as last year. This respite, though longer than usual, may turn out to be an interesting, but fleeting, blip.