The ninth seat on the Supreme Court has been vacant for two months.

But Antonin Scalia’s chair is not the only empty one in the vast federal judiciary, where several judgeships have remained unfilled for 30 months or more. Around the country, there are 84 of these vacancies, largely as a result of the Senate’s historically low rate of confirming President Barack Obama’s nominees. And since the beginning of last year, the number of unfilled seats and pending nominations have been steadily rising.

Down in the gears of the justice system, all those absent judges have taken a toll.

Because courts are obligated to find ways to meet speedy-trial rules, at least in criminal cases, the vacancies have not caused across-the-board delays1. But by all accounts, the unconfirmed nominees — combined with what advocates say is an insufficient number of judgeships overall — have forced the system to find sometimes extraordinary ways to make do with the few judges available.

Some judges, for example, are having to drive hundreds of miles to cover the empty seats. Less-qualified magistrate judges, senior judges who are supposed to be entering retirement, and visiting judges who fly in from other states, have all had to pitch in. And many of the remaining judges say that it’s hard, with such a lack of personnel, to give every case the attention it deserves.

In the worst-hit districts, including all four districts of Texas, some areas of Florida and California, Middle Alabama, and elsewhere, the situation is now considered an “emergency.”

Ron Clark, chief judge of the Eastern District of Texas, which has three judicial emergencies out of only eight total judgeships, says that "we’re managing the best we can — but if they don't get us another judge soon, you could start to see some more draconian kinds of delays.”

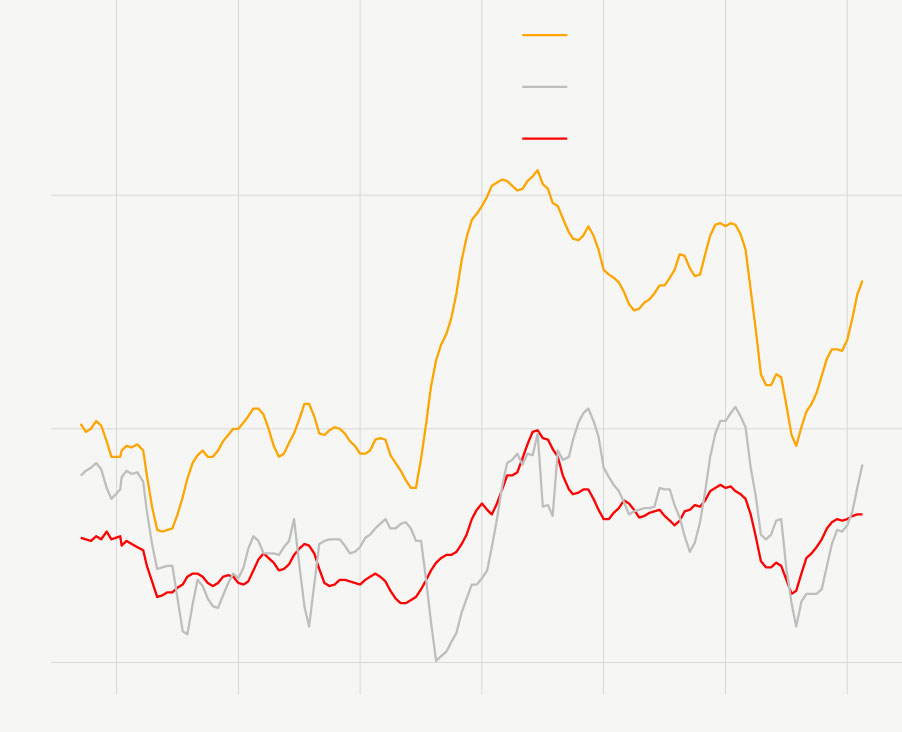

Vacant judgeships

Pending nominations

Emergency seats

100

50

0

2004

2006

2008

2010

2012

2014

2016

Vacant judgeships

Pending nominations

Emergency seats

100

50

0

2004

2006

2008

2010

2012

2014

2016

Vacant judgeships

Pending nominations

Emergency seats

100

50

0

04

06

08

10

12

14

16

A 2014 study by the Brennan Center for Justice found that the vacancies led to a host of negative consequences. Among them were unresolved motions, habeas corpus petitions waiting years to be heard (or being handled by law clerks instead of judges), judges spending less time on each case, and defendants pleading guilty because they believed a trial would not get the timely attention it deserved.

And in civil proceedings, where the Speedy Trial Act does not apply, longer wait times for trial are becoming more common.

Morrison C. England Jr., chief judge of the Eastern District of California, says that "cases that aren't the priority are going to get pushed back for years, literally."

In Middle Alabama, Ricky Martin, a pastor, had been allowing registered sex-offenders to stay in mobile homes surrounding his church — until the state legislature made it illegal for him to do so. Martin filed suit in August of 2014, and the local D.A. responded with a “motion to dismiss” a few months later. But a judge didn't get around to weighing in — in Martin's favor — until this April, and the case may not actually be resolved for two more years or longer.

The process would have taken only three to four months if there were more judges available, says Randall Marshall, legal director of the ACLU of Alabama.

But sometimes, the effect is the opposite: the proceedings get rushed.

Brian McGiverin, a civil-rights lawyer in Austin, Texas, says that because there are so few judges, the remaining ones are all overbooked. As a result, they often "give you a cramped amount of time for trial, regardless of how many witnesses you'd like to call."

McGiverin recently assisted in the case of a woman named Abieyuwa Ikhinmwin, who claimed that she was racially profiled, handled with excessive force, and wrongfully arrested by police in San Antonio.

He says the court tried to "fast-track" her lawsuit, threatening to dismiss it within 21 days unless she paid a fee and submitted additional information — which would not have happened when there were enough judges.

Clark, chief judge in the nearby Eastern District of Texas, says that "with so few of us, it's definitely harder to have the flexibility that a defense lawyer might want us to. So the answer sometimes has to be, ‘No, sorry, we can't offer that time in court.’ "

Meanwhile, the consequences of too few judges are worsened in the most geographically expansive districts.

"When there's a missing judge in a state like ours,’’ Clark says, “it's not like we can walk down the hall and take care of a trial for him — the trip from Beaumont to Plano is five and a half hours, and that's if the traffic is good."

He and the other judges in his district waste about two days a week on the road.

"We're one traffic accident away from the wheels falling off," he says.

As an additional stop-gap measure, the worst-hit districts are relying on pinch hitters.

In Middle Alabama, less-experienced magistrate judges (who are appointed directly by the district judges, rather than nominated by the president and confirmed by the Senate) have for several years been doing work once reserved for the district judges, from taking guilty pleas to overseeing evidentiary hearings. The district is also getting last-minute help from visiting judges, who have traveled from Iowa and Florida to pitch in.

"When there are judges who come in from elsewhere," says Christine Freeman, executive director of the federal defender's office in Montgomery, Ala., "they are strangers to us, to the prosecutor, to court officials, to the probation officers, to every single person involved in a case."

"That makes it very hard to predict outcomes for your client," Freeman adds.

But the lack of judges has perhaps fallen hardest on senior judges, who, because they are typically over 70 or 80 years old, usually take on 50 percent or less of a full caseload.

Instead, in Middle Alabama and elsewhere, their caseloads have been 150 or even 200 percent of normal.

"I'm 73, and I'd like to be able to say, ‘Look, I'm done, I want to spend more time with my family,’" says Michael Schneider, one of the senior judges in Eastern Texas. "I'm encouraged that the president has nominated someone, but I can't actually cut back until a nominee is approved."

"I'm going to be at this for awhile," Schneider adds. "It's frustrating."

England, the chief judge in Eastern California, says that senior judges are the only reason why vacancies haven’t become more of a crisis.

"We are living and dying with our senior judges," England says. "They're taking on cases they shouldn't have to, but that's what's saving us."

Of course, federal courts being overburdened is the symptom of more than simply a lack of nominations and confirmations.

Since 1990, Congress has not passed major legislation creating new judgeships2, even as the war on drugs, and now the surge in prosecution of undocumented immigrants, have jammed up the system with exponentially more cases.

As a result, by 2013, there was a 39 percent uptick in the number of overall filings, while only 4 percent more judges were added to handle all that extra work.

Throw in the higher-than-normal number of vacancies, and it’s a recipe for an overburdened judiciary. After a three-year wait, for instance, the Eastern District of California finally got a vacancy filled last October. But Chief Judge England says the crushing burden of too few judges hasn’t lessened.

“One way or the other, Congress would need to give this district more judges,” he says. “We need help — we have too many trials. I’m booked for 2016 and 2017 already.”