This year’s supreme court race in Pennsylvania is now the most expensive state supreme court election in U.S. history, according to data compiled by the Brennan Center and nonprofit election watchdog Justice At Stake. Going into Election Day, total spending had reached $15.9 million. The previous record was $15.2 million, set in 2004 in Illinois.

Judicial election experts anticipated high spending in this election, which will fill three seats on a bench of seven justices. Roughly $10 million of the overall spending has gone towards television advertising.

This year’s race for three open seats on the Pennsylvania Supreme Court began as a polite election. After a few years plagued by scandal — one justice convicted of felony campaign corruption, two others caught sending racist and pornographic emails — most of the candidates focused their messaging on restoring a sense of decorum and ethics to the bench.

But last week the campaign took an angry turn.

Political groups on the left and the right, some from outside the state, began buying airtime for ads attacking candidates for being soft on crime, often singling out their votes on controversial criminal cases. Unlike a candidate’s own campaign, outside groups have few limits on what they can say, and often do not have to report who funds them.

The nastiness of the campaign has raised the hopes of those who have been trying for decades to change the way Pennsylvania chooses its judges. A bipartisan group in the state’s House of Representatives has proposed a constitutional amendment to do away with open elections for appellate court seats and fill them instead through appointment. After four years, justices would have to stand for a yes-or-no retention vote, and again every 10 years after that. The bill was voted out of the house judiciary committee last week.

“The integrity of our justice system demands that we select judges based on more than voter turnout, name recognition or fund-raising ability,” Rep. Bryan Cutler, R-Peach Bottom, a co-sponsor of the bill, said in a statement. “We should be looking for the members of the bar with the highest qualifications, not just the best political skills.”

Cutler’s opponents, many of whom put money into the election campaigns, reject that view.

His proposal faces opposition from the trial lawyers’ association, unions, and groups focused on single issues like abortion. They and other opponents of the measure say there’s no proof that appointed judges are better suited for the job than elected judges, and that it’s important for voters to have a say in how the courts are run.

“The only thing that gets removed in a merit selection system is the voice of the people. The voice of politics and the voice of money still matter,” said Dan Fee, spokesman for the Pennsylvania Association for Justice (formerly known as the Pennsylvania Trial Lawyers’ Association.) Fee notes that judicial appointments can become political power plays, often resulting in unfilled seats. “The federal model is no model to emulate...the good thing about elections is that someone is going to win and that seat is going to be filled and cases will get heard.”

Pennsylvania has considered such an amendment since the 1980’s, but its proponents hope that recent scandals and an expensive, bitter election may push it through to become law. In 2013, then-Justice Joan Orie Melvin was convicted on felony charges for using government resources to run her campaign. Justice Seamus McCaffery resigned in October 2014 when it became public that he and several lawyers had sent each other pornographic and racist emails. Justice Michael Eakin, who remains on the bench, was recently implicated as well.

“It’s really the perfect storm,” said Suzanne Almeida, program director for Pennsylvanians for Modern Courts, a nonpartisan organization focused on court reform. “We’re seeing this incredibly expensive election, [and] this thirst from Pennsylvanians to figure out what we can do to fix the system.”

A local nonprofit, “Pennsylvanians for Judicial Reform” (led by the former chairman of the state Democratic Party), has spent nearly $1.3 million on ads attacking Republican-backed candidates, according to data compiled by the Brennan Center. On the other side, the Republican State Leadership Committee, which has spent millions in judicial elections across the country, bought $376,060 worth of ads against Democrats.

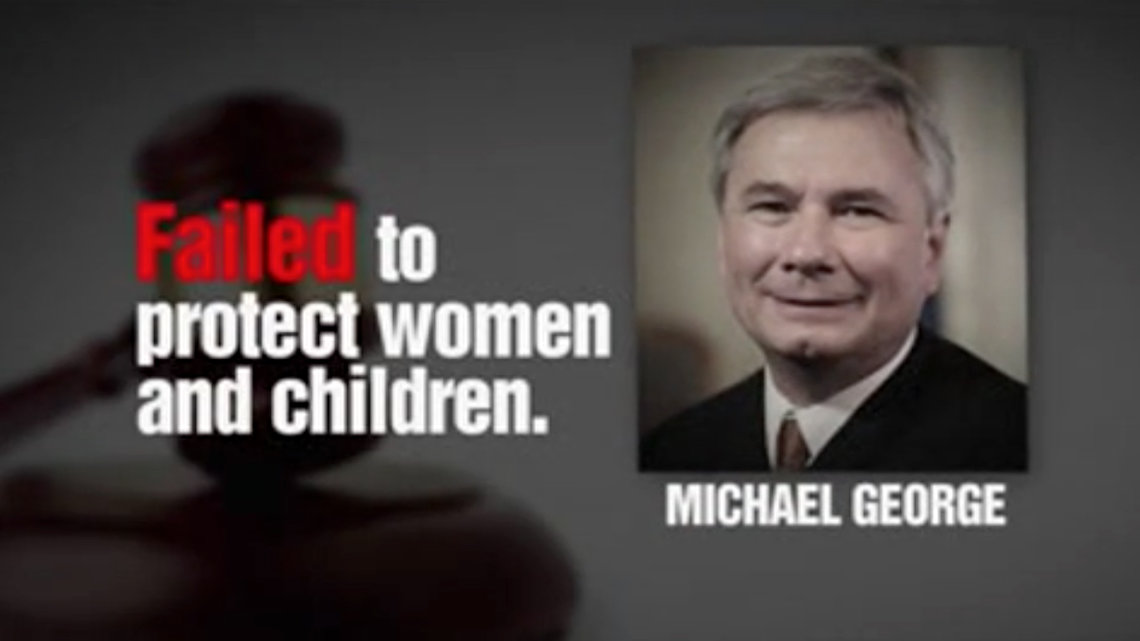

According to the ads, Adams County Judge Mike George “routinely handed out lenient sentences… one to a man who had raped a three-year-old girl.” Judge Kevin Dougherty, of the Philadelphia Court of Common Pleas, “shockingly allowed a young girl to be put in the custody of a convicted murderer.” Meanwhile, Judge Anne Covey of the Commonwealth Court and Judge Judy Olson of the Superior Court have rejected “early releases for rapists, child predators, and repeat violent criminals.”

The tenor of Pennsylvania’s election matches a nationwide trend of outside spending groups playing a growing role in local elections, often with negative, “soft-on-crime” smear campaigns. A new study by the Brennan Center and Justice at Stake, a judicial election watchdog, released today, found that political action committees and nonprofits accounted for 29 percent of spending in judicial elections in the 2013-2014 cycle, more than ever before. And of all television spots, a record 56 percent were about criminal justice. Eighty-two percent of attack ads were about a judge’s record on crime.

“What started as plaintiffs attorneys and labor on one side, business on the other, now you have groups like the [the Republican State Legislative Committee] playing a role,” said co-author Scott Greytak of Justice at Stake. “Fully 100 percent of attack ads were paid for by outside organizations. All of them.”

Recent studies suggest such advertising can carry over into criminal court decisions. A 2014 study by the American Constitution Society found that the more commercials there were in state supreme court races, the less likely justices were to vote in favor of a criminal defendant.

The U.S. Supreme Court has agreed to hear a case this term that asks whether a Pennsylvania judge’s tough-on-crime campaign influenced his decision-making. A death sentence in the case of Terry Williams, who was convicted of murdering the man who raped him, was reinstated by the State Supreme Court in 2014, after a lower court granted relief because of prosecutorial misconduct. Justice Ronald Castille refused to recuse himself from the decision — even though he was the former district attorney whose office pursued the death penalty for Williams, and who campaigned on a pro-death penalty platform when he ran for the Supreme Court in 1993.

“When I start talking about court reform, people’s eyes glaze over,” Castille told the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette at the time. “When I tell them about sending criminals to death row .... then they’re interested.” The High Court has not yet set a date for arguments.

Changing Pennsylvania’s system, which requires an amendment to the state constitution, would be a tough battle. The proposal is subject to approval by two consecutive legislative sessions and then a ballot question. Its supporters also face a struggle getting citizens to care about an issue that rarely tops voters’ list of concerns.

But some reformers are hopeful that the publicity over how the Supreme Court functions and how justices get there in the first place will inspire an outcry by voters.

“People are really starting to see that this isn’t some sort of esoteric thing that lawyers and a handful of academics care about,” Almeida said.