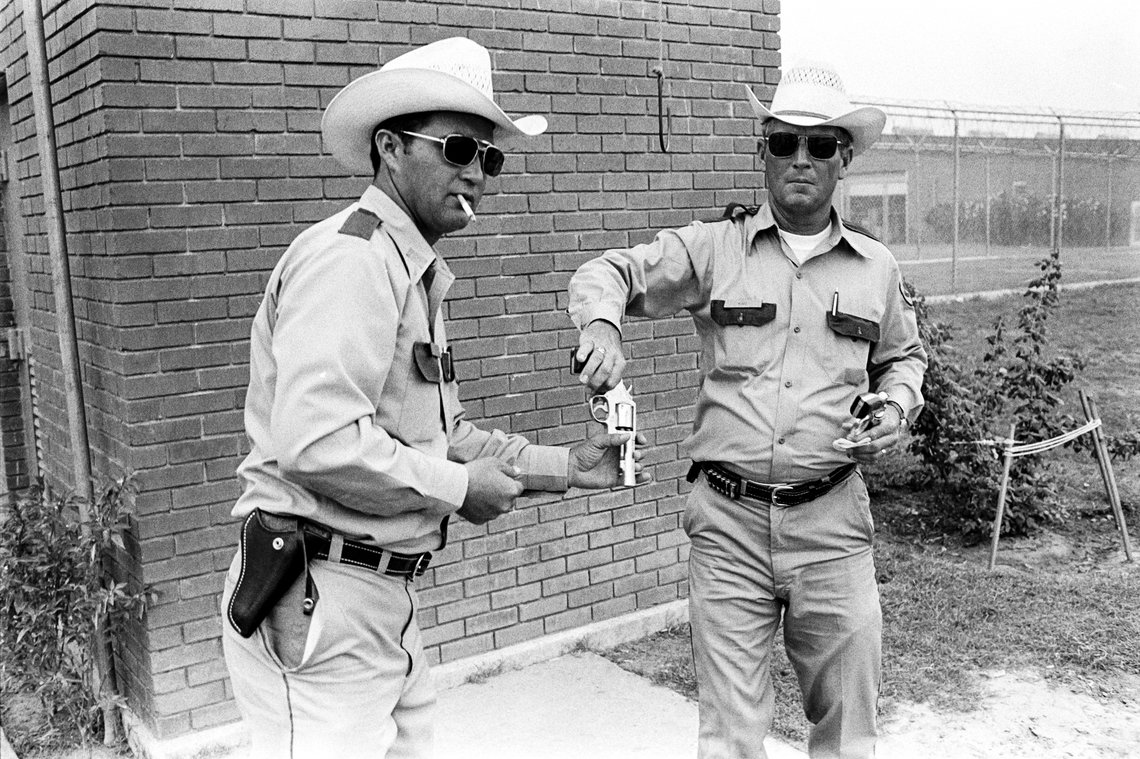

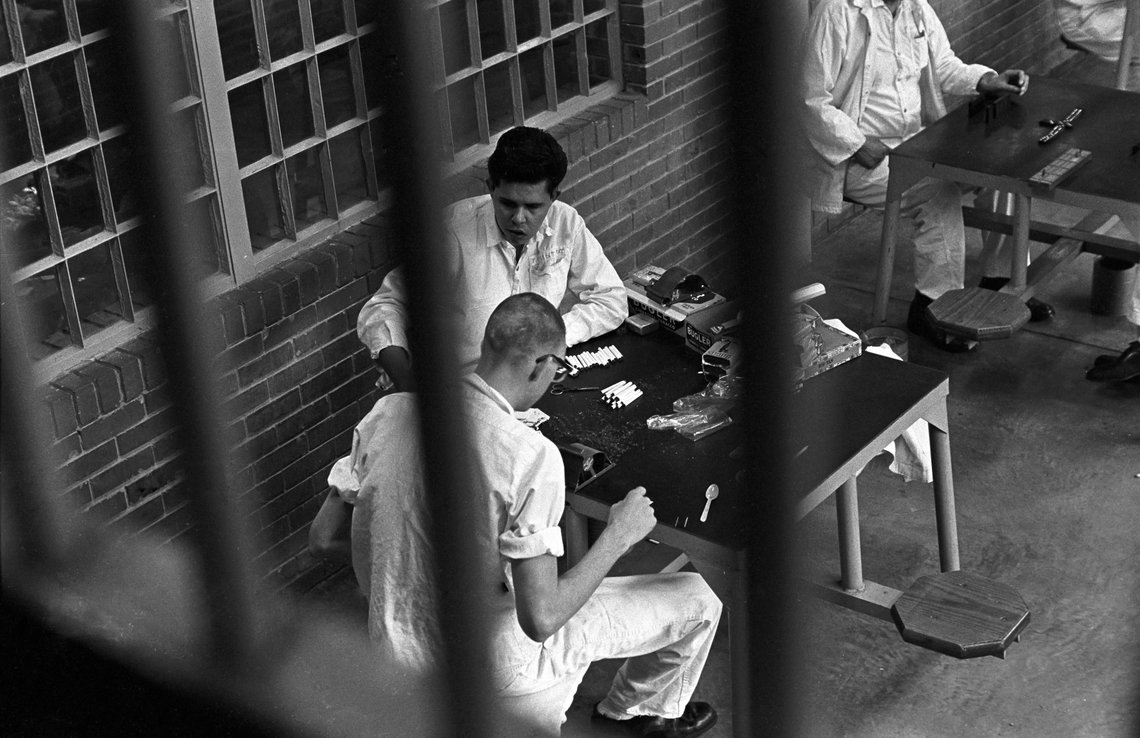

To understand the changes that American prisons underwent in the 20th century, there is no better visual archive than that of Bruce Jackson, a photographer, filmmaker, writer, and professor who secured the kind of access that journalists today can only dream of. In the 1960s and 1970s, Jackson took thousands of pictures of southern prisons, mostly in Texas and Arkansas, capturing an intimacy of daily life that reveals how, despite all the talk of politics and policy, these institutions are as much products of culture and society.

Now, a couple of generations later, Jackson’s work is getting another look. On April 28, the record label Dust-to-Digital released Jackson’s recordings of a Texas prisoner and singer named J.B. Smith. The documentary filmmaker Deborah Esquenazi is making a retrospective short film, which will premiere along with an exhibit in Austin, Texas, in June. (I was interviewed for the film.)

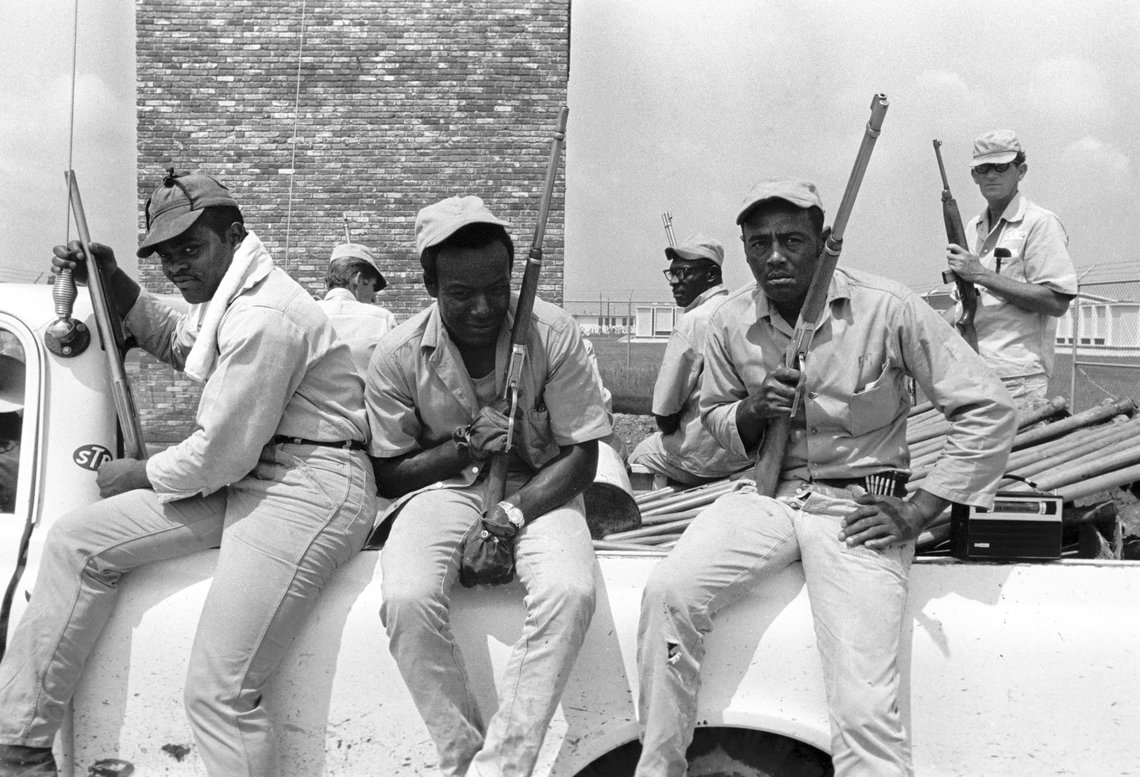

On the prison farms Jackson photographed, the prisoners, most of them black, worked much as their forefathers had as slaves, picking cotton, slamming hoes into soil, and singing to standardize the rhythm of their labor. By focusing on sight and sound — taking pictures, recording work songs — Jackson illuminated how these prison farms, a century after emancipation, preserved slavery’s spirit if not its law.

Many of the prison farms Jackson encountered had been family-owned slave plantations before the Texas Department of Corrections bought them. For the black men who had once been slaves and now were convicts, arrested often for minor crimes, the experience was not drastically different. As Jackson writes in his introduction to the 2012 photo collection Inside the Wire:

“...Everyone in the Texas prisons in the years I worked there used a definite article when referring to the units: it was always "Down on the Ramsey," not "Down on Ramsey," and "Up on the Ellis," not "Up on Ellis." It made no sense to me until I realized that nearly all of those prison farms had been plantations at one time, so it was like an abbreviated way of saying "I'm going to the Smith family's plantation," or "I'm going to the Smiths'."

This was the end of an era. Right after these photos were taken, in 1980, William Wayne Justice, a federal judge, issued a sweeping decision in the prisoner rights case Ruiz v. Estelle. Justice forced Texas prisons to modernize in all sorts of ways, from adding staff to improving working conditions to stopping the policy of allowing prisoners to guard one another with weapons. (Jackson photographed prisoners with rifles, an image unthinkable today).

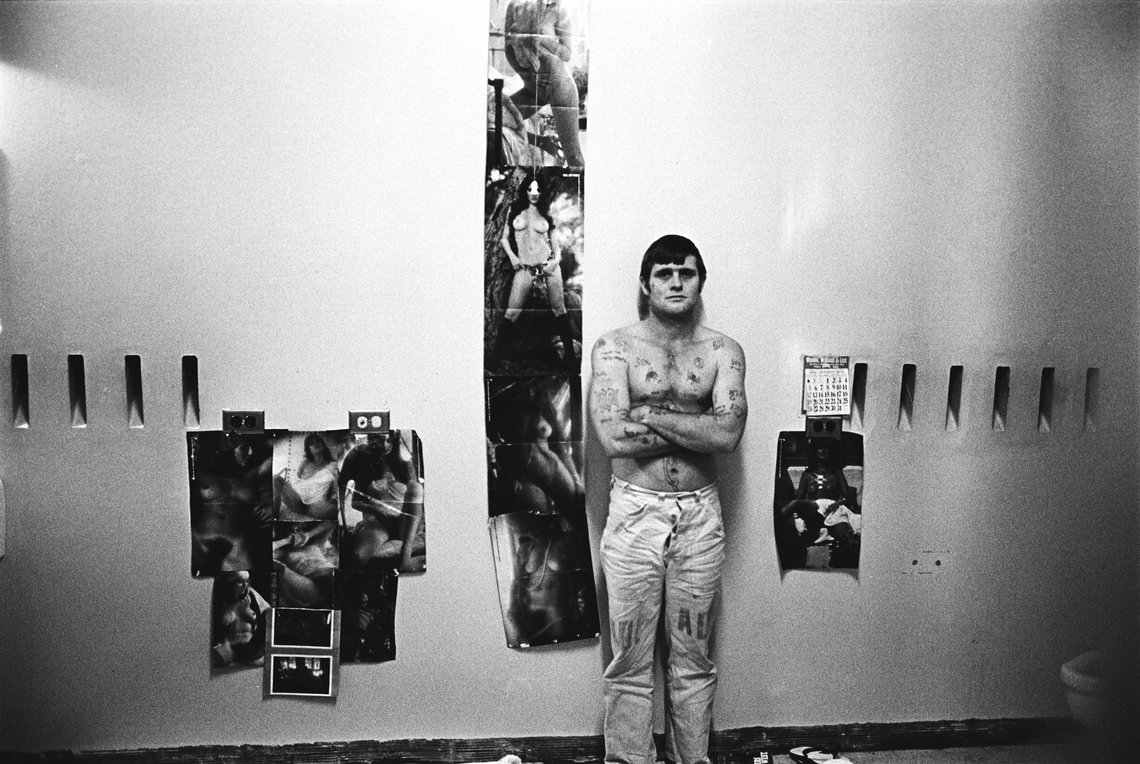

Over the next two decades, a wave of harsh sentencing laws around the country led to a prison-building boom. There were simply too many prisoners for field work alone. Gleaming new facilities were built in areas picked not for their farmland but for the populations of small-town residents who needed jobs as corrections officers. Some prisoners still worked in the fields, but many just passed their days in boredom.

We can now see the beginning of the end of this period off in the distance. Conservatives and liberals alike are starting to question the laws that produced such vast prison populations. The number of prisoners nationwide is far from an unambiguous decline, but 2014 marked the first time in more than three decades that federal facilities housed fewer prisoners than the year before.

Jackson started taking these photographs while still in his 20s. Now he is 78. That such a sweeping transition in the history of American prisons could take place during one man’s working career suggests that our habits of punishment may look timeless and entrenched, but that in reality change can happen quickly. Still, there are always traces of what came before.