The Justice Department released on Tuesday a 105-page agreement with the city of Cleveland listing dozens of required reforms for the police department. The mandated changes described in the consent decree, which will have to be approved by a federal judge, is one of the most detailed police reform plans announced by the Obama administration. It is also the first agreement between U.S. Attorney General Loretta Lynch and a local police department accused of widespread misconduct.

Changes to Cleveland Division of Police include: Prohibiting officers from pistol whipping suspects, placing them into neck holds, or deploying a Taser (or similar weapons) when they are running away; creating a multi-layer system of police oversight with a new inspector general post, more detailed investigations into civilian complaints against officers, and a revamped internal affairs office; and engaging in problem-oriented policing.

N o sooner had the video gone viral than the Justice Department announced it would again be scrutinizing the conduct of a local police force – this time in North Charleston, S.C., where a white officer had shot and killed an unarmed black man, Walter Scott, as he tried to run away.

Such announcements have become almost a national ritual in this moment of heightened sensitivity to police conduct, a ready federal response to the charges of bias and abuse that have risen against law enforcement agencies across the country. From Albuquerque to Ferguson, the arrival of the department’s Civil Rights Division has been meant to signal that Washington understands there is a problem and is committed to solving it.

But as the Obama administration has ratcheted up its oversight of state and local law-enforcement agencies, using a 21-year-old law to impose reforms on police forces that show a pattern of civil rights violations, questions about the effectiveness of those interventions have also been on the rise.

In cities like Detroit and New Orleans, officials have railed at the high cost of the Justice Department’s reform plans, including the multi-million-dollar fees paid to the monitors who make sure local officials comply with federal mandates. Elsewhere, some local officials have simply refused to accept what they view as meddlesome dictates, preferring to fight the demands for change in federal court.

Then there is the challenge of making the policing reforms last. Even where local leaders have embraced Washington’s prescriptions, Justice Department officials have increasingly found themselves returning to grapple a second time with problems they thought they had fixed.

“What we want to do is make sure that we are opening investigations and seeing sustainable reforms through to the end,” the head of the department’s Civil Rights Division, Vanita Gupta, said in an interview.

In cases like that of North Charleston, S.C., Justice officials have sometimes stepped in behind local prosecutors to examine whether police officers involved in a shooting used “objectively unreasonable force” against a suspect in violation of their Constitutional rights. The department seemed to take that approach in announcing Tuesday that it would investigate the death of Freddie Gray, a 25-year-old black man whose spinal cord was severed after he was arrested by the police in Baltimore.

But it is the more systemic investigations – in which state or municipal law-enforcement agencies are suspected of engaging in a “pattern or practice” of civil rights violations – that have both raised public expectations and sometimes fallen short of lasting reforms.

In Cleveland, where Attorney General Eric Holder appeared in December to decry a longstanding pattern of “unreasonable and unnecessary use of force” by the police, he neglected to mention that the Justice Department had investigated the city’s police a decade before. Justice officials settled that earlier case after the city promised to revise its policing methods.

Other recurring problems have emerged in police departments in Miami, New Orleans and New Jersey, all of which had promised to carry out major changes in response to Justice Department investigations that turned up evidence of discriminatory policing.

In interviews, Justice Department officials acknowledged that some of their earlier reform plans have fallen short. At times, they said, the department chose benchmarks that did not adequately measure the conduct they were trying to change. In other instances, federal officials did not sufficiently monitor or enforce the reforms they had sought.

“We continue to learn from each of our agreements and, frankly, improve on the way we enforce the statute,” said Mark Kappelhoff, another senior official in the Civil Rights Division. “That learning continues up until today.”

The Justice Department’s growing attention to local law-enforcement agencies comes at a time of intense public scrutiny of police forces around the country.

When local prosecutors have failed to indict police officers for shooting unarmed suspects or committing other apparent excesses, critics have often pressed Washington to act under the statute that criminalizes the use of “objectively unreasonable force” by an officer of the law.

Holder’s Justice Department has charged more than 400 law-enforcement and corrections officers with various violations of constitutional rights in recent years. But its occasional inquiries into police shootings have often left the activists disappointed – as they were when the department concluded in March that the killing of Michael Brown in Ferguson did not violate federal law.

The Civil Rights Division conducts its broader, “pattern or practice” investigations under a different federal statute. That law took shape after the 1991 roadside beating of Rodney King by white officers of the Los Angeles Police Department, and was finally enacted in 1994.

That statute, known as 14141 after its section of the U.S. Code, allows the Justice Department to investigate almost any report of police actions that suggest a pattern of violations of citizens’ constitutional civil rights. Where the allegations are upheld, the department can seek agreement with local governments on policing reforms or – as it has done more aggressively under President Obama – go to the federal courts to force changes under closely monitored consent decrees.

Justice officials also announced the most recent of those inquiries on Tuesday, saying they would examine complaints that police in the central Louisiana town of Ville Platte and sheriffs of the surrounding Evangeline Parish had detained people without cause.

With both the individual and systemic cases, the remedies might include ordering police agencies to conduct new training, set up computerized databases, install dashboard cameras on patrol cars or change the way they handle citizen complaints. The agreements are sometimes overseen by retired police officials who have implemented similar reform plans in their own cities.

The investigations are intended to serve as examples. The office that conducts the inquiries, the Special Litigation section of the Civil Rights Division, has only about 50 lawyers, some of whom concentrate on issues other than police accountability. They field complaints by the hundreds. “They have to pick their battles,” said Stephen Rushin, a visiting assistant professor at the University of Illinois College of Law who has studied the process.

The Ferguson inquiry that began last September, for example, involved a relatively tiny police force of 54 officers and a town population of barely 20,000. But it required hundreds of Justice Department interviews, the review of 35,000 pages of police records and an extensive statistical analysis of police and court data, among other steps, the report noted. And though the investigation prompted the swift resignations of Ferguson’s police chief, city manager and municipal judge, the hardest part may be yet to come: negotiating a reform agreement that the city’s surviving officials will not only accept but implement fully.

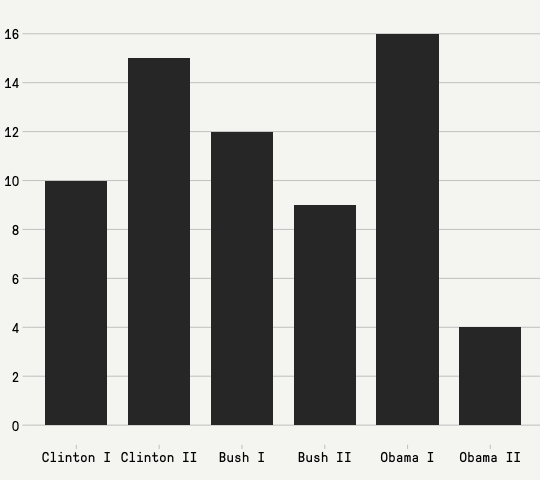

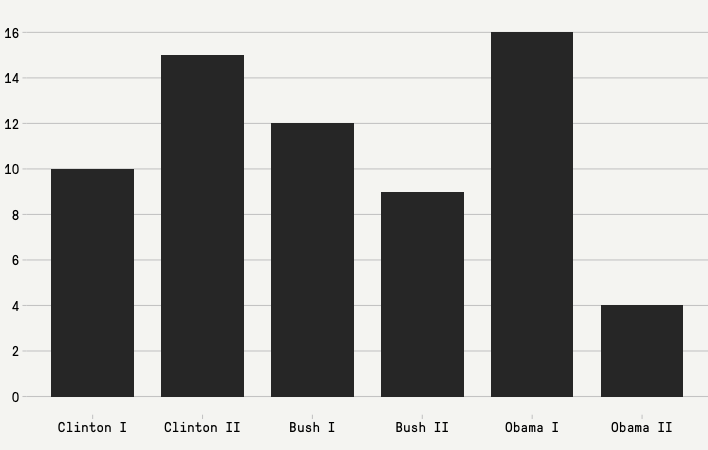

F or most of the Clinton and Bush administrations, a primary critique of civil rights activists and legal scholars was that the policing investigations were too few and far between to resonate nationally. According to one recent study, the Justice Department investigates fewer than 0.02 percent of the country’s nearly 18,000 state and local law-enforcement agencies each year.

As in Ferguson, the Civil Rights Division has tried to pick its shots for maximum effect. “We have to think about how we can have a force-multiplying effect through our investigations,” Gupta said.

But even where the department’s interventions have been successful, they have rarely been smooth.

One of its more-noted successes, with the Los Angeles Police Department, began with an inquiry in the summer of 1996. It then took almost five years of investigation, data analysis and negotiation before a consent decree was reached. The court-supervised monitoring then continued for more than a decade until early 2013.

The LAPD’s progress was halting. During the first seven years the police department spent under federal supervision, citizen complaints about police stops, arrests and racial profiling all rose at various times, although excessive-force complaints fell. Even after the department adopted a more successful approach to curb racial profiling, a federal judge extended his oversight for another four years.

“Obviously these things don’t happen overnight,” said William Yeomans, a former senior official of the Civil Rights Division. “There are always forces that will pull police departments towards reverting to practices that got them into trouble in the first place. It is not something that you do once and then walk away from.”

Justice officials cited the department’s investigation of racial profiling by the New Jersey State Police, which led to a consent decree in 1999, as an example of how it has emphasized the more rigorous collection and analysis of policing data to measure whether policy changes have made the desired impact.

The department found that New Jersey troopers stopped black and Latino drivers much more frequently than white motorists, and it ordered changes in policing that were to be tested against data on the race and gender of drivers stopped in the future.

But in a forthcoming study of New Jersey traffic stops between 2005 and 2007, researchers at Columbia University found that while the disproportionate stops of minority drivers fell, African-Americans and Latinos were still almost three times more likely to be searched than whites. In addition, researchers found that white troopers were 20 percent more likely to search minority drivers than were black troopers.

“That’s the problem with consent decrees,” said Jeffrey Fagan, a Columbia Law School professor who oversaw the study. “They did everything that was asked of them except stop profiling.”

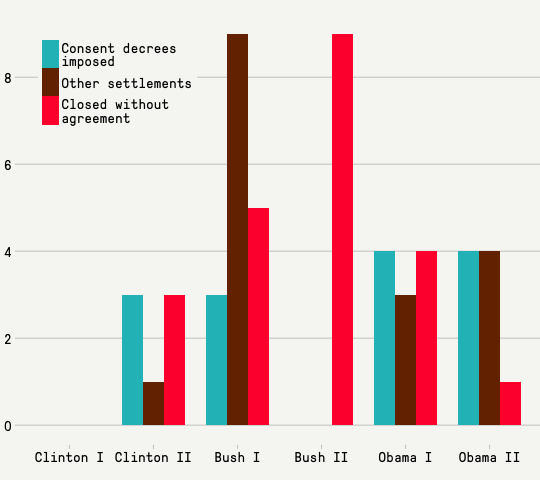

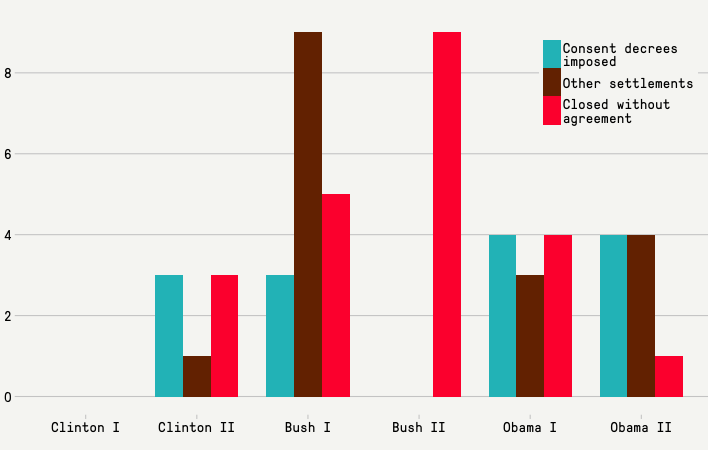

Over the six years following the law’s passage, the Clinton administration launched 25 investigations into discriminatory policing and the excessive use of force, more than half of which led to court-sanctioned consent decrees or memorandums of agreement.

Many of those inquiries came in big, racially and ethnically mixed cities like Los Angeles and Detroit, where political leaders were generally sensitive to complaints of discrimination and sometimes welcomed federal intervention as a way to compel police unions to accept changes in policy.

The Bush administration approached the law very differently.

As he was campaigning for the presidency in 2000, then-Gov. George W. Bush told the country’s biggest police union: “I do not believe the Justice Department should routinely seek to conduct oversight investigations, issue reports or undertake other activity that is designed to function as a review of police operations in states, cities and towns.”

His Justice Department generally upheld that view. Of 12 excessive-force and discriminatory policing inquiries begun in Bush’s first term, only two resulted in settlements during his administration, and neither of those was a consent decree. No consent decrees were imposed during Bush’s second term.

“I generally did not want to be in the business of running law enforcement agencies at the Justice Department,” said Bradley Schlozman, who oversaw the Special Litigation section during part of that time.

Under Schlozman, the section shifted some of its staff from policing inquiries to other duties. A 2008 report by the Justice inspector general also accused Schlozman of violating department policy and federal civil service law by pushing for conservative attorneys while trying to weed out those he considered “pinkos” or “libs.” (Federal prosecutors declined to press charges in the matter and Schlozman, who denied politicizing the hiring process, said he had made his comments about liberals in jest.)

While political support for the 1994 civil rights law declined sharply under Bush, other shortcomings of the statute also came into focus, former officials and legal scholars said.

“It was a desperately needed piece of legislation,” said Yeomans, who now teaches law at American University. “But it took the Department of Justice a while to figure out what to do with it.”

In Cleveland, which was plagued by discrimination and excessive-force complaints, the Justice Department concluded a four-year investigation in 2004 by reaching an out-of-court settlement with the city. The deal, which Justice officials monitored for a year, included a prohibition against officers from firing at fleeing vehicles unless someone’s life was in danger.

But by 2013, Justice Department investigators were back in the city. This time they came at the request of the mayor, to look into another rash of police shootings and other issues. Among the problems they reviewed was a high-speed car chase that began when officers mistook the car’s backfire for a gunshot, and ended with a barrage of 137 police bullets that killed both the unarmed driver and his passenger.

“Obviously the reforms that were attempted there didn’t take hold,” Kappelhoff, the Justice Department official, said.

Justice officials have also found themselves back in Miami, where seven black men died in police shootings during an eight-month span ending in 2011. In 2006, the department had closed an earlier civil rights investigation of the Miami police after the force pledged to make a series of changes sought by Washington.

“Unfortunately, many of the systemic problems we believed were fixed have reoccurred, evidenced by a steady rise in officer-involved shootings,” the then-head of the Civil Rights Division, Thomas Perez, wrote to Miami’s mayor and police chief in July 2013.

Perez (who is now the Obama administration’s Labor secretary) made similar statements about the New Orleans Police Department in 2011, when federal prosecutors released a scathing, 158-page report that portrayed a force rife with bias and abuse. Only seven years earlier, the Bush administration had closed a lengthy Justice Department investigation of the force after it promised to track officers’ conduct with a new data-management system and overhaul its handling of citizen complaints.

O ver the last few years, Attorney General Holder has made the law enforcement investigations a higher priority. This year, his department asked Congress for a $2.5 million budget increase to add 13 attorneys and six investigators to its Civil Rights Division’s police misconduct team, department documents show.

Rather than simply checking off mandated changes in policy, as it did in the past, the agency has emphasized the more sophisticated analysis of data to assess change. “We call our last six years our 2.0 era of consent decrees,” Kappelhoff said.

A 2012 agreement with Seattle, for example, requires local police to report the rate of arrests, where an officer used excessive force, and how many times police department policy was violated in each incident. In Albuquerque, where a consent decree was signed last November, the police will track officers’ use of force and their interactions with the mentally ill, and set up a review panel to analyze the results.

What the Justice Department has not managed to do is to make its reform plans any less costly to carry out.

In Detroit, where the police department came under two separate consent decrees in 2003 (one related to a high number of police shootings, the other tied to the illegal detention of witnesses), the city later sued its former federal monitor, Sheryl Robinson Wood, demanding a $10 million refund for her work.

City officials noted that while Woods was billing the Detroit police as much as $193,680.55 a month, she was also carrying on a secret romantic relationship with the then-mayor, Kwame Kilpatrick, who is now serving a 28-year federal prison term for public corruption. At the time, the city was also sliding into bankruptcy.

(Lawyers for the city eventually reached out-of-court settlements with Wood's former employers: for $1.75 million with Kroll Associates, Inc., the investigations firm, and $350,000 with two law firms where she had worked.)

In New Orleans, Mayor Mitch Landrieu sought to have a federal judge block a Justice Department consent decree, arguing that it would cost the city at least $10 million. "I'm completely and totally committed to reforming the police department, but my job is to protect all of the taxpayers of New Orleans," Landrieu said. The judge rejected the appeal.

Justice Department officials acknowledge that the re-training, data collection and monitoring they demand often come at substantial taxpayer expense. But they contend that the failure to fix systemic police problems carries even greater costs – not only in public-relations problems and community mistrust, but also in the settlement of civil lawsuits, dismissals and the like.

Some legal scholars and civil libertarians have argued that the costs of the refusing to change discriminatory police practices should be even higher. They have pressed the Justice Department to aggressively use of its authority under Title VI of the 1964 Civil Rights Act, which allows the department to cut off federal funds to any program or agency that is found to engage in discrimination.

Even some police departments that have been investigated repeatedly, the activists note, have continued to draw generous grants from the Justice Department itself for equipment, training and other needs.

For instance, in September 2013, six months after the Justice Department began a new investigation into discriminatory policing in Cleveland, the city received a grant of $1.25 million to hire 10 new police officers and another $1 million for crime-prevention efforts. The next year, just before Attorney General Holder accused the force of “systemic deficiencies,” it was awarded $1.9 million more to hire 15 new officers.

In theory, the civil rights law gives the federal government wide latitude to cut off funds. But while the department has sometimes accused local police agencies of violating Title VI rules – as it did in Ferguson – it has avoided using the law to cut off police assistance funds.

“Title VI, at the end of the day, is more of a threat than anything else,” said Robert Driscoll, a former senior Justice Department official under President Bush.

Driscoll, who supervised the Special Litigation Section between 2001 and 2003, has also found some weaknesses in the Justice Department’s “pattern or practice” interventions, including its lack of subpoena power to compel the release of internal documents from local police forces.

In Maricopa County, Arizona, Driscoll represented the famously contentious sheriff, Joe Arpaio, when he became the first in a series of local law-enforcement officials to defy a Justice Department lawsuit under the 1994 law.

At the behest of the Phoenix mayor, Phil Gordon, Justice officials began in 2008 to investigate Arpaio’s campaign to enforce federal immigration laws, which included stopping Latino drivers without cause and detaining those suspected of being undocumented.

When Justice officials sought access to sheriff’s department records and facilities, Arpaio refused. “It being him, we just extended the finger and said, `No, we’re not going to cooperate,’” Driscoll recalled.

After the Justice Department sued Arpaio for the access under Title VI of the Civil Rights Act in 2010, the county cut off funding for the litigation, and he was forced to settle. Justice officials then found that Arpaio and his office had “intentionally and systematically” discriminated against Latinos in traffic stops, unfounded arrests and jail practices.

But Arpaio refused to accept the oversight of a federal monitor, so the department sued again, winning an injunction that bars deputies from stopping drivers solely on the suspicion that they might be undocumented. On April 15, the Ninth Circuit court of appeals upheld most of the reforms that a district judge had ordered the sheriff’s office to undertake, including re-training and the filming of traffic stops, but limited some of the freedom of the court-appointed monitor.

“We know that there are going to be police departments that are recalcitrant, that are not interested in engaging in reform,” Gupta, the Civil Rights Division chief, said. “And for those, we obviously have all the tools that we use across the department to really push them to do so.”

But Arpaio’s capitulation has not dissuaded some other local forces from fighting back as well. Over the past few years, Justice officials have been challenged by the Seattle police officers’ union; the Missoula, Montana county attorney; and the Fundamentalist Church of Jesus Christ of the Latter Day Saints, a polygamous Mormon sect, among others.

Like Arpaio in Arizona, the sheriff of Alamance County, N.C., Terry Johnson, also refused to share his records with federal investigators after they found that he, too, was illegally targeting Latino drivers. This time, the Justice Department responded by filing a civil lawsuit to force discovery.

By the time a federal judge heard the case last summer, the county had already spent more than $450,000 on the litigation. Since issuing its findings of discriminatory policing in 2012, the Justice Department has also withheld what the county attorney, Clyde Albright, claimed was more than $2.4 million in federal drug asset forfeiture monies that would have gone to the sheriff’s office; a Justice official said the actual amount was considerably less than that. The Department of Homeland Security also suspended Alamance from a program that offers training and other support to local law-enforcement agencies for their help in enforcing federal immigration laws.

“This is what the federal government does,” Albright complained in an interview. “They just want to come in and take over your law-enforcement agency. They march in the door and say you are guilty of all these things. My reaction is, `Says who?’”

A ruling in the federal lawsuit is expected soon.